Last night? It seemed more than thirty hours since that pair of hands had played We Won’t Go Home Until Morning.

Mrs. Marino brought a decanter and glasses by way of rapprochement.

“Perhaps you’d prefer a highball, Mister Vine?”

“Thanks. No. Straight across the board.” I was ready for a stimulant. “Your sister’s in a pretty desperate fix, Mrs. Marino.”

“I know. I wanted to go to New York to be with her, but she didn’t think the authorities would permit it. And now this awful news on the radio about Dow Lanerd; Tildy must be absolutely stricken.”

“Broke her up, all right.”

“Such a sweet man. So considerate. Not at all the sort you’d expect to do a frightful—”

Nikky reappeared, skirted and sweatered. She seemed annoyed with her mistress’s sister but waited respectfully while Mrs. Marino urged me to stay in one of the spare bedrooms, no trouble at all, really; they’d feel badly if I didn’t — after the peculiar reception I’d been given.

When Mrs. Marino had gone, I put it up to Nikky in words of one syllable.

“You were in the room when the guard was knifed. You saw it all.”

“No. I was in the bathroom. Washing a pair of gloves.”

“What’s the diff? Why all the guff about what the man wore?”

She rubbed her cheek, where I’d butted her. “It’s so absurd. We were doing all we could to hide it; then he had to end it himself. What’s the use?”

“Lanerd?”

“Of course.” She switched on a big console radio, tuned it in to some platter parade, low enough so we could talk but loud enough to keep anyone upstairs from hearing what we said. “After dinner, we both went into her bedroom. Mister Lanerd had a key to her room; he let himself in. They began to argue — she’d written him a note calling off plans to go to South America with him, and he began to maul her. I can’t stand anyone being mean to my baby, so we had a tussle. He swore at me, slapped me. Tildy ran into the other room to ask the guard to help with him.”

“Neither Lanerd nor Roffis will dispute any of it.”

“Tildy will tell you it’s true. Roffis came in; he tried to put Mr. Lanerd out, even had the hall door open. He struck Mister Lanerd in the face; it made him furious. He seized a knife from the serving-table the waiter’d just put out in the hall, stabbed the guard in the back. We couldn’t believe he was dead for a little, then we dragged him to the closet, dumped him in there, and held a council to decide what to do.”

I really was impressed. What she’d said checked perfectly with Auguste’s story, so far.

“We decided Mr. Lanerd would have to get cleaned up; there was blood on his coat and shirt. Right after the stabbing, we thought the waiter would be able to see us dragging the body to the closet, so I ran over and pushed the bedroom door to. There was blood on my gloves, I still had them on, some of it got on the door. That’s what made us think of the stain on Mr. Lanerd’s coat. So he went across the hall to change.”

“Auguste said someone came out of the bedroom. But he didn’t recognize the man. He recognized Lanerd quickly enough a little later when I was in the room.”

“That old goof. He’s half blind. He couldn’t recognize his own mother unless he heard her talking. Mr. Lanerd bumped right into him, but didn’t say a word. Auguste grunted but never knew who it was. Tildy telephoned the other man, Hacklin, told him that Roffis had run some intruder out of the room and hadn’t come back, would he come over and take us to the studio. So he did. Of course I had to go down in the service elevator.”

“Ridiculous rule.” I quoted, “‘Only nurses with infants allowed in guest elevators.’ Yair. Go on.”

“That’s all. Except at the studio, Tildy kept reassuring herself that she’d had to do it, she couldn’t let him go to jail.”

I remembered what MacGregory had said. It checked.

“Why’d you skip out on Hacklin?”

The music faded. There was a station break. A signature. Five minutes of the latest news from the wire room of WLEX.

She said, “Tildy was afraid we’d say the wrong thing, or do something to give Mr. Lanerd away. So I took her to my uncle’s until we found out how the wind was blowing.”

It checked with Auguste, with the producer. But not with Dow Lanerd’s waiting in 21MM with his automatic ready for business. Why was that?

“Oh, we’d all been under such a strain, expecting that cochon Gowriss to sneak in and murder us both in our beds. We pulled the bureau up against the bedroom door every time we snatched a ten-minute nap. Mr. Lanerd was as scared of Gowriss as we were. He thought, several times, he’d been followed by a man in a taxi—” she paused to listen.

The zombi voice from the console said:

“... after a hair-raising chase for seven miles through crowded traffic on the Boston Post Road at speeds in excess of eighty miles an hour, Connecticut State Police tonight shot it out with Albert Gowriss, notorious criminal. Gowriss and a woman companion were critically wounded by gunfire and subsequent smashup...”

“One thing about you, Miss Narian. There are fewer and fewer people who can contradict your story.”

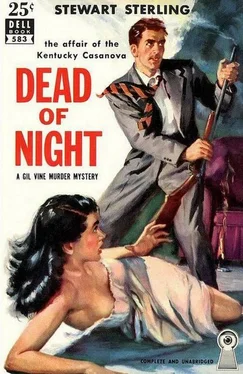

Chapter thirty-two:

Amnesia?

In the Plaza Royale, we’ve one old girl who’s been living in a tower suite for nine years. She hasn’t been out of the hotel more’n a dozen times annually. Says she considers our metropolitan palacio the positive peak of luxury living. Point is, she can afford to live anywhere she wants to — and the place she left to come to New York was Fayette County, Kentucky! Man!

If I could afford one of those Bluegrass country homes, I’d never envy anyone who lived in New York. Not to mention Carmel, Cal., the Isle of Capri, anywhere you like on the Riviera. Or what have you.

When I woke up in Lovelawn’s west guest room next morning, my vista was a golden green sea of rippling corn, an emerald knoll where jet-black cattle browsed, a bronze mare and her nuzzling colt silhouetted against the sun on the crest. Prettier than Central Park. Much.

There was more to it than My Old Kentucky Home atmosphere, too. A shaving-kit the Syrian had set out in my private shower room. Tasty old ham with eggs goldenrod, corn cakes and country butter, clotted cream and coffee our breakfast chef should have taken a cue from — served in solitary splendor off Limoges china, by a Negress who had as much aplomb as any of our Gallic waiters.

I couldn’t understand how Tildy Millett would have been willing to give up all that. She’d have had to, of course; Dow Lanerd wouldn’t have been the type to move into any wife’s home.

The females of the household had petit déjeuner upstairs. The youngster’d been up for hours, was ky-hootin’ around the yard on a palomino pony, buckarooing all over the place.

I had seconds on old ham, made a note to ask Emile why we couldn’t get flavor like that on our menu, went over Nikky’s story, step by step.

It dovetailed neatly with the official version. Maybe too neatly. I’d stayed up half the night with her, trying to discover discrepancies. She’d had answers for everything.

Why’d she described the murderer’s suit as dark instead of cream-colored? To divert suspicion from “her baby’s” fiancé.

What reason could Tildy have had for claiming the man who killed Roffis looked like Roy Yaker, an acquaintance of Lanerd’s? Must have been because Yaker was the first person who’d come to Tildy’s mind, when I’d insisted on some description. The pollster’d been loitering around 21CC and the corridor with what Nikky diagnosed as lecherous intent. Once he’d been in the elevator with Tildy and managed to let his hand come into contact with her — Nikky illustrated with scornful distaste — her behind! Tildy’d ignored him. But she’d have remembered him, unkindly.

Читать дальше