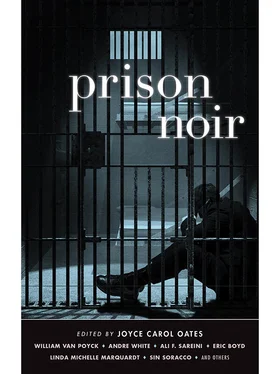

Джойс Оутс - Prison Noir

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джойс Оутс - Prison Noir» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: akashic books, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Prison Noir

- Автор:

- Издательство:akashic books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Prison Noir: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Prison Noir»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Prison Noir — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Prison Noir», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In one of the most bizarre and original stories in this collection, “A Message in the Breath of Allah” by Ali F. Sareini, a strange sort of vernacular poetry is spoken by a psychotic killer — unless this devout Muslim is a religious mystic: “Only the fading light of day was visible through the barred window as I entered the cells at Coldwater. The shadows were silent.”

The very antithesis of a psychotic, compulsive killer is the naive young Mexican illegal immigrant of Marco Verdoni’s “Immigrant Song,” who finds himself imprisoned in freezing Michigan without ever quite comprehending what is happening to him, or why:

It was spring when [Celso] came to the States; summer when they arrested him. The jail didn’t have any windows, so when the van came to take him to prison, he didn’t know what the brown slush was on the floor. He thought it was vomit.

“It’s a blizzard,” the driver said, pulling out of the jail. “Total whiteout.”

Poor Celso, knowing no English, finds himself convicted of felony murder in a drug dispute; he thinks he will be released at the age of twenty-two, and learns belatedly that he must serve a minimum of twenty-two years. Interesting to note that the most bloody, barbaric killings in Prison Noir take place in this story, in a turkey slaughterhouse in which the young Celso works until he is fired and forced to support himself by selling drugs.

Most of the inmates in these stories are mature in their acceptance of “guilt,” and resigned to their fates; most, in fact, are older prisoners, and several are old enough to be grandfathers. (As the self-admitted murderer of “Angel Eyes” acknowledges at the age of seventy-eight, he has outlived his own children.) In the volume’s most sensational story, “3 Block from Hell” by Bryan K. Palmer, a serial killer boasts of having killed 198 men—“Each one of them deserved it. You don’t believe me? I’ll let you be the judge”—and his identity, revealed only at the story’s end, is a shocker. In Andre White’s “Angel Eyes,” an intensely narrated story with a stunning ending, it is noted:

Fish! Every day they come in younger and younger. Pretty soon they’ll be babies, and I’ll end up having a work detail changing diapers. . I was once like the one or two young bucks of a batch that ain’t a cur. Oh, I ’member wings in my stomach flapping ’bout when I done my first stretch, was eighteen years old and ready for whatever. I’d seen some wild ones come through that bit hard, like a piranha in a fishbowl.

The entertaining “How eBay Nearly Killed Gary Bridgway” by Timothy Pauley provides a most unusual perspective on the infamous Green River Killer (Washington State, 1980s and 1990s, convicted in 2003), as an enterprising fellow inmate and his mercenary wife drum up business selling the serial killer’s autograph online. As P.T. Barnum once observed, no one ever went broke underestimating the taste of the American public.

The blunt opening of “Milk and Tea” by Linda Michelle Marquardt takes us immediately into the spiritual paralysis of Women’s Huron Valley (Michigan), or “Death Valley”:

Her feet must have been only two feet from the ground as her body dangled like a rag doll from the door hinge. There was chaos: screams, officers running, hands shaking, fellow inmates praying, everyone watching with morbid curiosity as her limp body crashed on the cement floor, cracking her skull. Not that it mattered: she was already dead. Damn! I was jealous. .

In flashback scenes of unrelieved tension we learn how the depressed and suicidal protagonist has been sexually abused and threatened with death by her late, psychotic husband — ironically, “a licensed attorney in three states [with] a master’s degree in medical anthropology. Still, he’d never had a job — he died at the age of thirty-two and had never worked a day in his life.”

In “I Saw an Angel” by Sin Soracco, a story with an unexpectedly upbeat ending, we are privy to the intimate lives of women prisoners in a facility in Corona, California, where time passes with stultifying boredom “built on broken trivialities. . thinking, but to no real purpose, just mind beeps puddling up in the swamp.” In both “I Saw an Angel” and “Milk and Tea”—the only stories by women writers in the volume — the sympathetic and intelligent protagonists are seen as victims of crimes perpetrated against them by men, rather than as criminals themselves. But the stories have radically different endings. (Please note: we tried very hard to locate more stories by women prisoners. But since less than 10 percent of inmates in US prisons are female, two contributions out of fourteen isn’t so very disproportionate. 1)

In the cleverly constructed “Shuffle” by Christopher M. Stephen, a veteran of decades of incarceration in the segregation unit of an Illinois prison is agitated by having to share his cell with another man who, by degrees, comes to dominate him as his old, long-repressed crimes are invoked; until at last, the older prisoner’s final defense is taken from him and he is left utterly bereft—“You can’t gamble what you’ve already lost.” Another feat of sustained suspense, the almost entirely conversational “Rat’s Ass” by Kenneth R. Brydon, limns the exposure of a criminal con man/sociopath in staccato dialogue reminiscent of David Mamet. 2)

The most ambitious of Prison Noir stories is the poetically composed “Bardos” by Scott Gutches, divided into four quarters in mimicry of the four cyclical seasons; partly a eulogy for an older inmate who has died unexpectedly, and partly a eulogy for the protagonist whose sensitivity and intelligence suggest a tragic disparity between character and fate. He is living a suspended, bardo-like existence between life and death, the “bardo” state being, according to the ancient revered Tibetan Book of the Dead , “a progression of moments before, during, and after life leaves the body.” The protagonist is transfixed in his bardo-state, unable to break free of the cyclical existence of things. The great sin of his life seems to have been his betrayal of his father, who had originally betrayed him by having led a secret homosexual life; the prisoner allowed his father to die when the man’s life might have been prolonged, and is consumed with guilt: “Sometimes remorse and guilt come first, then the act which justifies it.”

Another ambitious, introspective story is Zeke Caligiuri’s “There Will Be Seeds for Next Year,” narrated by an inmate who has tried, and failed, to commit suicide by slashing his wrists: “They were strange times at Stillwater, the walled-in fortress of buildings sitting on the Minnesota side of the St. Croix River.” An eerie malaise seems to have fallen over the facility, infecting prisoners and guards alike, and provoking younger inmates to set fires in their own quarters, out of frustration and despair. In this place, each day resembles the next: “We basically lived in a hallway that attached to everything: cellblocks, chapel, gym, yard, school, chow”—a place of “sleepwalking zombies.” (Many of the inmates, mentally ill, are heavily sedated.) The story ends with a fiery apocalypse that brings with it a kind of redemption:

It burned for every soul this place ever held captive. . It told us that for all the things we knew this place to be, even the oldest of institutions can burn, break down into ash. I was proud to watch its destruction. Sirens blared, and the ship sank. . To see the animals burn down the zoo. I swear I could see the faces of all those trapped souls escaping. . Let the motherfucker burn. There would be seeds for next year.

In the sparely written “The Investigation,” a veteran inmate is summoned to the office of a prison official who is investigating a brutal murder, with the hope that the man will identify the killer or killers. The setting could be a generic prison in Michigan, California, or Connecticut; it happens to be Florida. The inmate is a man named Cotton who has been a witness to innumerable murders over the years, who has never informed on any fellow prisoner. Now, as if for the first time, Cotton takes particular note of “a dusty, moth-eaten county fair keepsake” in a corner of the investigator’s office: “a large stuffed rattlesnake, fangs bared, ready to strike, coiled around a stuffed, ratty, furred mongoose, snarling in response, the two forever frozen in locked mortal combat. .” Cotton stares at this display of what might be a “metaphorical message”—or what might have no meaning at all. The reader is struck by the pathos of the situation: the inmate’s wasted life and the tawdriness of the combat-to-the-death between stuffed rattlesnake and stuffed mongoose, as between prison administrators and inmates, inmates and inmates, and inmates divided against their own selves. This is the material of comedy or farce, yet also the material of tragedy. Keenly we feel the inmate’s yearning for meaning in a moral void, but we are not at all certain that meaning is within his reach. Like most of the protagonists of the stories collected in Prison Noir , Cotton faces an unresolved, uncertain future.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Prison Noir»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Prison Noir» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Prison Noir» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.