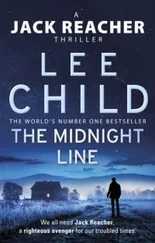

‘Do you know how to fight?’ Reacher said.

‘No. But you do. You’ve done OK against these guys so far.’

‘Rusty, I’ve been happy to help. But I’m not going to be here for ever.’

‘Don’t go just yet. Please. Stay a while. I’ll pay you. I have savings.’

‘I don’t need money. And I wouldn’t take your savings anyway.’

‘OK then. Forget money. I’ll pay by teaching you about computers. Help you get into the twenty-first century. Or the twentieth, anyway. Or at least to use a cell phone.’

Rutherford had a point about there being no guarantee of his safety if he ran. And it wasn’t safe for him to stay, either. Not on his own. Not with federal agents who walked away from their promises to protect him. And not with people like Marty on the lookout, under orders to report his whereabouts.

‘What if I stay?’ Reacher said. ‘For a day or two. And in return, you don’t teach me anything about computers?’

‘It’s a deal.’ Rutherford held out his hand. ‘What do we do now? Stay out of sight? Hope they don’t try again?’

‘No,’ Reacher said. ‘We go on the offensive. Tell me, what time does the doorman in your building go off shift?’

‘He said he pulled a double today. He’ll be there till ten tonight.’

‘Good. There are some preparations we need to make. But first there’s a visit I want to pay. Grab your phone. Call up the telephone directory. There’s an address I need you to find.’

Reacher had heard stories over the years about people coming home, drunk or stoned, and going into the wrong house. Sometimes they were found there later, asleep in a bed or passed out on the floor. Sometimes they got shot by the home’s rightful owner. Sometimes they did the shooting, thinking their own home had been invaded. Reacher had heard plenty of excuses over the course of his career. The idea of a mistaken address was one he’d always found hard to swallow. That changed when he arrived in Holly’s neighbourhood.

He could picture it freshly built. Two miles west of town. One squat rectangular house after another. One rectangular lot after another. All on a succession of right-angle streets. All carved out of the surrounding fields by the flood of money flowing around the state in a wave of postwar development. It would have been easy to mistake one for another when they were freshly minted. Approaching the wrong one would still be a straightforward mistake to make despite the minor variations that had crept in over time. There was a newer roof here, less bleached after fewer years in the ferocious Tennessee sun. An extension there, defying the neighbours’ uniform contours. Some houses had fresher paint. Some had greener lawns. And others had owners who’d abandoned their attempts at decorating and gardening altogether.

Reacher walked up the path leading to the house next to Holly’s, but he wasn’t making a mistake. It was a deliberate move. Because of Holly’s front door. She had the worst kind, from a cop’s perspective. It had no windows so you couldn’t see in from the outside. There was a peephole so anyone on the inside could see out. And it was made out of wood panels. They were thin. Useless for security. They could be kicked through in a second. About as far from a boulder rolled across the entrance to a cave as you could get. But that kind of door did have one advantage for anyone defending the premises. Easy as it would be to open, there’d be no need. They could fire right through it. A shotgun would be the best bet. Not that Reacher expected a waitress to be lurking in the hallway with a full load of double aught. But it’s what you don’t expect that gets you killed.

There was no answer at the neighbour’s door. Reacher rang the bell again and waited. He allowed time for the demands of old legs or young babies. Then when he was reasonably certain the house was unoccupied he made his way down the side of the garage. He selected a section of fence which wasn’t overlooked and where the wood seemed at its strongest and vaulted over into Holly’s back yard.

It looked like someone’s hopes for the space had been high. Once. A long time ago. Approximately half the area was given over to a lawn. Its curved edge followed the shape of a sine wave and it was finished with a border of rustic bricks, set end-on. Only now the mortar between them was cracked and the grass was scorched and dead. In the far corner was the wooden skeleton of an arbour. Reacher guessed it had been conceived as a place to relax. Maybe with a bottle of wine in mind. Maybe with a little romance. Only now the vines that had been trained over it were shrivelled and dry. The trellis was smashed in several places. And the chain holding up the swinging love seat was detached on one side.

The part of the yard that wasn’t grass had been covered with flagstones. They clearly hadn’t seen the business end of a broom for many months. There was also a round metal table, painted green, with an overflowing ashtray and a pair of chairs. They were set near a sliding door. It was made of glass. Much better, Reacher thought.

Reacher stayed close to the wall and moved until he was close enough to look in through the door. He could see one person. A woman. She was wearing a pink robe and sitting at a small table with a mug of coffee in front of her, untouched. She was leaning with her head in her hands and her hair was loose, cascading forward. Reacher tapped on the glass. The woman sat bolt upright. She turned to the door. Reacher got a clear view. It was Holly. Her face was creased with shock. And fear. And she had a giant bruise around her left eye. She tipped her head until her hair covered her face again, then waved Reacher away.

Reacher shook his head.

Holly waved for him go.

Reacher made as if to knock again. He pulled his arm way back. Made it clear that if he did knock, it was going to be loud.

Holly jumped up, hurried to the door, slid it open, pushed Reacher back, and stepped outside. She slid the door shut, trying to be gentle, but made sure it was fully closed.

‘What are you doing here?’ Her voice was a stern hiss. ‘You’ll get me in trouble.’

‘Looks like you managed that without my help,’ Reacher said. ‘Who did that to your face?’

Holly tugged at her hair. ‘No one. I was in a rush getting ready for work yesterday and it was late when I got home and I was tired so I forgot I left my wardrobe door open and I walked right into it. Anyway, my clumsiness is none of your business. What do you want? And why are you in my yard?’

‘I’m here as a representative of the International Fellowship of Luddites. We’re having a recruitment drive and after last night it occurred to me that you would be an ideal candidate.’

Holly’s good eye narrowed and she took half a step back. ‘What’s a Luddite?’

‘Someone who’s opposed to progress. Especially any that comes from new technology. Named after an English guy. Ned Ludd. He broke a bunch of machines back in the eighteenth century.’

‘Are you crazy? I don’t care about some ancient English guy. And I’m not opposed to progress.’

‘Then why don’t you want the town’s computers working again? What other reason could you have for wanting them to stay locked down?’

Holly shook her head. ‘You’ve got this all wrong. I work at the diner. Our computer’s working fine. Why would I care about the town’s?’

‘The bozos you set on me last night certainly cared. I assumed you shared their feelings.’

‘What bozos? Those guys have got nothing to do with me.’

‘Sure they do. They’re your friends. Or your boyfriend’s friends.’

‘I don’t have a boyfriend.’

‘So your friends, then.’

Читать дальше