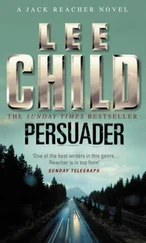

I came out into the courtyard and squatted down in the angle of the walls and loaded my pockets. I had the chisel if things needed to stay quiet, and I had the Glock if it was OK to go noisy. Then I scoped out my priorities. The house first, I decided. There was a strong possibility that I would never get another look at it.

The outer door to the kitchen porch was locked, but the mechanism was crude. It was a token three-lever affair. I put the bent spike of the bradawl in like a key and felt for the tumblers. They were big and obvious. It took me less than a minute to get inside. I stopped again and listened carefully. I didn’t want to walk in on the cook. Maybe she was up late, baking a special pie. Or maybe the Irish girl was in there doing something. But there was only silence. I crossed the porch and knelt down in front of the inner door. Same crude lock. Same short time. I backed off a foot and swung the door open. Smelled the kitchen smells. Listened again. The room was cold and deserted. I put the bradawl on the floor in front of me. Put the chisel next to it. Added the Glock and the spare magazines. I didn’t want to set the metal detector off. In the still of the night it would have sounded like a siren. I slid the bradawl along the floor, tight against the boards. Pushed it right through the doorway and into the kitchen. Did the same with the chisel. Kept it tight against the floor and rolled it all the way inside. Almost all commercial metal detectors have a dead zone right at the bottom. That’s because men’s dress shoes are made with a steel shank in the sole. It gives the shoe flexibility and strength. Metal detectors are designed to ignore shoes. It makes sense, because otherwise they would beep every time a guy with decent footwear passed through.

I slid the Glock through the dead zone and followed it with one magazine at a time. Pushed everything as far inside as I could reach. Then I stood up and walked through the door. Closed it quietly behind me. Picked up all my gear and reloaded my pockets. Debated taking my shoes off. It’s easier to creep around quietly in socks. But if it comes to it, shoes are great weapons. Kick somebody with your shoes on, and you disable them. With your shoes off, you break a toe. And they take time to put back on. If I had to get out fast, I didn’t want to be running around on the rocks barefoot. Or climbing the wall. I decided to keep them on and walk carefully. It was a solidly-built house. Worth the risk. I went to work.

First I searched the kitchen for a flashlight. Didn’t find one. Most houses on the end of a long power line spur have outages from time to time, so most people who live in them keep something handy. But the Becks didn’t seem to. The best I could find was a box of kitchen matches. I put three in my pocket and struck one on the box. Used the flickering light to look for the big bunch of keys I had left on the table. Those keys would have helped me a lot, but they weren’t there. Not on the table, not on some hook near the door, not anywhere. I wasn’t very surprised. It would have been too good to be true to find them.

I blew out the match and found my way in the dark to the head of the basement stairs. Crept all the way down and struck another match with my thumbnail at the bottom. Followed the tangle of wires on the ceiling back to the breaker box. There was a flashlight on a shelf right next to it. Classic dumb place to keep a flashlight. If a breaker pops the box is your destination, not your starting point.

The flashlight was a big black Maglite the length of a nightstick. Six D cells inside. We used to use them in the army. They were guaranteed unbreakable, but we found that depended on what you hit with them, and how hard. I lit it up and blew out the match. Spat on the burned stub and put it in my pocket. Used the flashlight to check the breaker box. It had a gray metal door with twenty circuit breakers inside. None of them was labeled gatehouse . It must have been separately supplied, which made sense. No point in running power all the way to the main house and then running some of it all the way back to the lodge. Better to give the lodge its own tap on the incoming power line. I wasn’t surprised, but I was vaguely disappointed. It would have been sweet to be able to turn the wall lights off. I shrugged and closed the box and turned around and went to look at the two locked doors I had found that morning.

They weren’t locked anymore. First thing you always do before attacking a lock is to check it’s not already open. Nothing makes you feel stupider than picking a lock that isn’t locked. These weren’t. Both doors opened easily with a turn of the handle.

The first room was completely empty. It was more or less a perfect cube, maybe eight feet on a side. I played the flashlight beam all over it. It had rock walls and a cement floor. No windows. It looked like a storeroom. It was immaculately clean and there was nothing in it. Nothing at all. No carpet fibers. Not even trash or dirt. It had been swept and vacuumed, probably earlier that day. It was a little dank and damp. Exactly how you would expect a stone cellar to feel. I could smell the distinctive dusty smell of a vacuum cleaner bag. And there was a trace of something else in the air. A faint, tantalizing odor right at the edge of imperceptibility. It was vaguely familiar. Rich, and papery. Something I should know. I stepped right inside the room and shut off the flashlight. Closed my eyes and stood in the absolute blackness and concentrated. The smell disappeared. It was like my movements had disturbed the air molecules and the one part in a billion I was interested in had diffused itself into the clammy background of underground granite. I tried hard, but I couldn’t get it. So I gave it up. It was like memory. To chase it meant to lose it. And I didn’t have time to waste.

I switched the flashlight back on and came out into the basement corridor and closed the door quietly behind me. Stood still and listened. I could hear the furnace. Nothing else. I tried the next room. It was empty, too. But only in the sense that it was currently unoccupied. It had stuff in it. It was a bedroom.

It was a little larger than the storeroom. It was maybe twelve-by-ten. The flashlight beam showed me rock walls, a cement floor, no windows. There was a thin mattress on the floor. It had wrinkled sheets and an old blanket strewn across it. No pillows. It was cold in the room. I could smell stale food, stale perfume, sleep, and sweat, and fear.

I searched the whole room carefully. It was dirty. But I found nothing of significance until I pulled the mattress aside. Under it, scratched into the cement of the floor, was a single word: justice . It was written all in spidery capital letters. They were uneven and chalky. But they were clear. And emphatic. And underneath the letters were numbers. Six of them, in three groups of two. Month, day, year. Yesterday’s date. The letters and the numbers were scratched deeper and wider than marks made with a pin or a nail or the tip of a scissor. I guessed they had been made with the tine of a fork. I put the mattress back in position and took a look at the door. It was solid oak. It was thick and heavy. It had no inside keyhole. Not a bedroom. A prison cell.

I stepped outside and closed the door and stood still again and listened hard. Nothing. I spent fifteen minutes on the rest of the basement and found nothing at all, not that I expected to. I wouldn’t have been left to run around there that morning if there was anything for a person to find. So I killed the flashlight and crept back up the stairs in the dark. Went back to the kitchen and searched it until I found a big black trash can liner. Then I wanted a towel. Best thing I could find was a worn linen square designed to dry dishes with. I folded both items neatly and jammed them in my pockets. Then I came back out into the hallway and went to look at the parts of the house I hadn’t seen before.

Читать дальше