For her heart was broken Betty had said, she’d been engaged to a wonderful man she had loved so much, Major Matt Gordon of the US Army Air Corps & they were to be married several years before but Major Gordon died in a plane crash far away in India & his body never recovered & Betty confessed she’d been so broken-hearted & a little crazed she had told her fiancé’s family that they had actually been married—in secret—& had had a little baby that had died at birth; & the family refused to believe this & scorned her & kept her from them & finally pretended that “Elizabeth Short” did not exist—so she had ruined her chances with the Gordon family, & was sick to think of it— So much that I have lost, I hate God sometimes He has cursed me . & I said to Betty Don’t ever say that! Don’t give God any reason to hurt you more.

& Betty cried in my arms like a little girl as no one had ever seen her except me—for Betty did not wish anyone to know her weakness, she said—& swore me to secrecy, I would never tell; & I held her & said We can help each other, Betty. We will!

But then, you could not trust her. My new lipstick missing, & one of my good blouses—& I knew it was Betty doing what Betty did which was take advantage of a friend. & I knew a time was coming when we would split up—& Betty would have no place to stay for the girls of Buena Vista were getting sick of her & then what? Where would she go?

That January night it was cold & rainy & I came back to the Buena Vista finally in a taxi by 1 AM & climbed the stairs to the second floor & there was the door to our room shut & I thought Maybe Betty is here: maybe Betty did not feel well & did not go out at all tonight —& when I came inside I stumbled in the darkness & groped for the light switch & I could see someone in Betty’s bed sprawled & helpless-seeming—limp & not-breathing—& when I managed to switch on the light I saw that it was just bedclothes twisted in Betty’s messy bed, coiled together like a human body.

“Oh Betty! Gosh I thought it was you .”

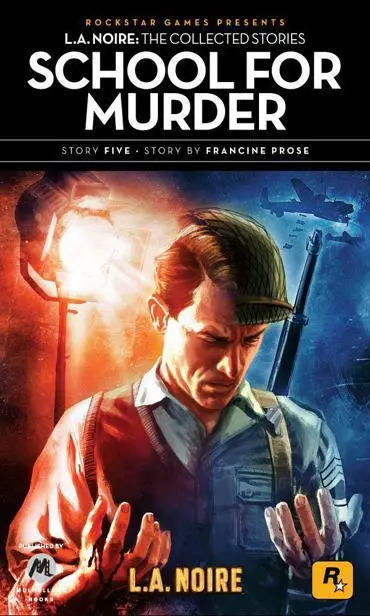

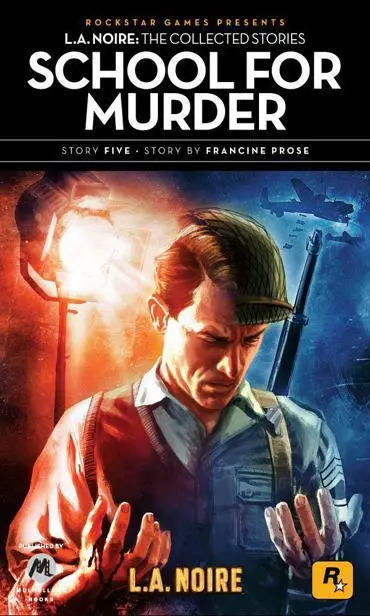

SCHOOL FOR MURDER

Francine Prose

All summer I kept hearing people say desperate . Actors are always eavesdropping on strangers, picking up phrases, gestures, stuff we can use. And wherever I went, whenever I listened in, I heard: desperate, desperate, desperate!

At the pharmacy, I heard a dame say, “Hon, if my landlord evicts me, things are gonna get desperate.” A buddy of mine said, “If my girl in New York doesn’t call pretty soon, man… I’m desperate.” I overheard a bum on Skid Row say, “That jerk better pay me back, I don’t care how desperate he is.”

The funny thing was, this was 1947. Desperation was yesterday’s mashed potatoes. Happy days were here again. The Depression was over, the war was over, we’d dropped the bomb, we’d won. Guys like me had defended our country, and girls appreciated that. I’d been in the battle of Okinawa. That was pretty much all I had to say and gals would feel like it was their personal mission to heal whatever was broken.

In L.A., the studios were popping out pictures like bunnies having babies. L.A. was the place to be! As soon as I got discharged, I spent a week with my mom in Seattle, then stuck out my thumb and headed south. Hollywood, here I come!

For a while, it seemed I was getting paid back for risking my life and seeing things I shouldn’t have seen. Horrors I kept seeing in those nightmares I’d wake up from, drenched and shaking.

At first, good things were coming my way. No great things, I wouldn’t say great. But I was making a living.

Everyone knew about the stars who’d started out as extras, or with one-sentence walk-ons that made some producer sit up and ask, “Who’s that? Get me his agent on the phone.” Bit parts were a foot in the door. I was glad to get them.

If you’ve seen enough pictures from those years, you’ve probably seen me. I’m the croupier in that scene where Barbara Stanwyck wins all that money. I’m a ranger out searching for the kid right before Lassie finds him. I give Bing Crosby directions in Road to Utopia .

For a while life looked rosy. Then… my luck turned. People lost interest. If I’d had a dollar for every time I heard the line, “My agent stopped returning my calls,” this story wouldn’t have happened. I wouldn’t have needed the money. But it wasn’t about the money. Or maybe a little about the money. Maybe the reason I kept hearing people say desperate was because it described my state of mind—and my bank account.

At Gatsby’s, the actors’ bar where my unemployed friends and I hung out, the clientele was so desperate we never used the word.

Chuck was my agent at the time. The one not returning my calls. The boys at Gatsby’s gave me advice. They said, “Vince, you need to get heavy with the guy.” You could ask why I took the advice of other unemployed actors. But I did. I made a real pest of myself, called my agent twenty times a day. His receptionist hated my guts. But she had to pick up the phone.

Chuck finally called back. Maybe his receptionist had read him the riot act. He’d blackmailed someone into blackmailing someone into getting me a part.

I’d been drinking the night before, needless to say. Chuck called at nine and gave me the address of a studio. Not one of the majors—but not somebody’s garage in Pasadena, either.

I asked what the picture was called. He said, “ Not Guilty. ” Then louder, “ Not Guilty! With an exclamation point!”

I asked when I could see the script. Chuck said he didn’t have one. I should just show up on the set and they’d take it from there. Then he said, “To sweeten the pot, the director is Harry Wattles.”

“You’re kidding me,” I said.

Everyone knew Wattles’s name. He’d been a rising star who’d fucked himself, or more specifically, the girlfriend of some big-shot producer. Now he’d been busted down to doing low-budget noir films. But everybody saw them. He had a reputation.

Chuck said, “You should be paying them for a chance to work with Wattles. Though I don’t know how I’d calculate my commission on that. Relax, big guy. I’m joking.”

The shoot was in Pasadena on a soundstage that smelled like a cross between a dead rat and a recent electrical fire. Everyone was running around—frazzled, yelling their heads off. But you couldn’t tell what anyone was doing, and they didn’t seem to know, either. In other words, a film set.

Wattles looked even stranger than he did in his photos. It was weird to have a name like Wattles and look like a hammerhead shark. It was also weird to look like that and get any girl you wanted.

Someone intercepted me on my way to Wattles, someone else intercepted that person, who was intercepted by the one who actually got to talk to Wattles. Wattles came over and shook my hand. He was surprisingly friendly, but like a friendly shark smiles before he chews your leg off.

He said, “Nice to meet you. Love your work.”

“You do?”

“Yes,” he said. “Sorry we couldn’t find you a part with some meat on its bones.”

“Gee, Mr. Wattles, I’ll take a skinny part.” I sounded like a moron!

“But I have to tell you, Vince.” Wattles was one of those guys who says your name every five seconds. I never trusted guys like that, but maybe I’d been wrong. “Your role is crucially important. It sets the tone for the whole picture.”

I was definitely wrong. Harry Wattles was a prince.

“Really?” My voice was climbing. I thought, You just screwed yourself out of a job unless they’re looking for boy sopranos.

Читать дальше