"Is that all the story?" he asked, and knew that it was not.

She shook her head.

"Something else happened in the same year. An American salvage ship, the Salvor, went out to search a wreck off Cape Charles. The Merida, which sank in 1911 and took the Emperor Maximilian's crown jewels to the bottom with her — another million-pound cargo. They didn't find anything. And fish don't wear jewellery."

"I remember the Terschelling Island fireworks — the Lutine. But that's a new one."

"It's not the only one. Two years before that another salvage company went over the Turbantia with a fine comb. She was torpedoed near the Maars Lightship in 1916, and she had seven hundred and fifty thousand pounds' worth of German bullion on her — then. The salvage company knew just where to look for it. But they didn't find it… That was quite a small job. But in 1928 the Sorima Company made an official search for a collection of uncut diamonds and other stones worth more than a million and a quarter, which were on board the Elizabethville when another U-boat got her on her way back from South Africa during the war. Well, they found a lot of ammunition in the strongroom, and thirty shillings in the safe; which didn't show a big dividend."

"And this has been going on for years?"

"I don't know how long. But just look at those three jobs. They average out at over a million pounds a time. Leave out all the other official treasure hunts that are going on now, and all the other millions that may have been sneaked away before the authorised salvage companies get there. Leave out all the other jobs that haven't been discovered yet. Doesn't it tell you anything?"

Simon Templar sat back and let the electric tingles play up his vertebrae and toe-dance airily over the back of his scalp. His whole body felt the pulse of adventure in exactly the same way as a sensitively tuned instrument can detect sounds inaudible to the human ear. And to him the sounds were music.

In that short silence he had a vivid picture of all the far reaches of the sea on which the Corsair cushioned her light weight. He saw the lift of storms and the raw break of hungry rocks and death stealing out of the invisible to give the waters their treasure. He saw the green depths, the ultimate dim places under the spume and sapphire beauty; saw the vast whale-shapes of steel hulls sunk in the jade stillness, and the gaunt ribs of half-forgotten galleons reaching out of the fronds of weed. What unrecorded argosies might lie under those infinite waters, no one would ever know. But those that were known, those that the sea had claimed even in the last four hundred years… His imagination reeled at the thought. The Almirante Florencia, lost treasure‑house of the Armada, foundering in Tobermory Bay with £2,000,000 in plate and jewels. The Russian flagship Rurik, sunk on the Korean coast with two and a half million pounds in specie. The sixty-three ships of the Turkish Navy sent to the bottom of Navarino Bay in 1827 with £10,000,000 between them. The Chalfont Castle, with her steering carried away and her plates sprung below the waterline in the great storm of that very year, drifting helplessly down on to the Casquets to the west of Alderney, and sinking in twenty fathoms with £5,000,000 of bar gold in her strong-room. Odd names and figures that he had heard disinterestedly from time to time and practically forgotten crept back from the hinterlands of unconscious memory and staggered him… And he saw the only possible, the only plausible corollary: the ghost pirate stealing through grey dawns to drop her divers and her steel grabs, the unsuspected gangsters of the sea who had discovered the most pluperfect racket of all time.

He would have thought that he had heard every note in the register of crime, but he had never dreamed of anything like that. The plot to swindle the Bank of Italy by means of one million perfectly genuine 100-lire bills, for his share in which he was entitled to wear the pendant of the Order of the Annunziata in the unlikely event of his ever attending a State function, was mere petty pilfering beside it. Sir Hugo Renway's scheme for pillaging the cross-Channel gold routes was mere clumsy experiment in comparison. And yet he knew that the girl who sat looking at him was not romancing. She threw up the stark terse facts and left him to find the link; and the supernatural creep of his nerves told him where the link was.

Her grey eyes were on him, tempting and challenging as they had been when he first saw her with the lights striking gold in her hair and the sea's damp on her slim shoulders; and in his mind he had a vision of the black expressionless eyes of the hooknosed man who stood up in the boat and lied to him.

"Why?" he said, with a dreamy rapture in his slow deep breath. "Why didn't I know all this before?"

"Perhaps you were too busy."

"Anything else could have waited," said the Saint, with profound conviction. "Except perhaps the Bank of England… And is that what you're detecting?"

She took a cigarette from his pack, and a light from the butt between his fingers.

"Yes. I work for the Ingerbeck Agency — we have a contract with Lloyd's, and we handle a lot of other insurance business. You see, where we work, there's no ordinary police force. Where a ship sinks, the wreck is nominally under the protection of the country that covers the water; but if the underwriters have paid out a total loss the salvage rights belong to them. Which means precisely nothing. In the last fifty years alone, the insurance companies have paid out millions of pounds on this kind of risk. Of course they hoped to get a lot of it back in salvage, but the amounts they've seen would make you laugh."

"Is it always a loss?"

"Of course not. But we've known — they've known — for a long time, that there was some highly organised racket in the background cheating them out of six figures or more a year. It's efficient. It's got to be. And yet it's easy. It has clever men, and the best equipment that money can buy. We went out to look for them."

"You?"

"Oh, no. Ingerbeck's. They've been on it for the last five years. Some of their men went a long way. Three of them went too far — and didn't come back." She met his eyes steadily. "It's that sort of racket… But one of them found a trail that led somewhere, out of hundreds that didn't; and it's been followed up."

"To here?"

She nodded.

"You see, we came to a brick wall. The men could get so far, but they couldn't go on. They couldn't get inside the racket. Two of those who didn't come back — tried. We couldn't take a chance on anything drastic, because we've no official standing, and we hadn't any facts. Only a good guess. Well, there was one other way. Somewhere at the top of the racket there must be a head man, and the odds are that he's human."

He took in the grace of her as she lounged there in the oversized bathrobe, understanding the rest.

"You came out to be human with him."

The turn of her head was sorcery, the sculpture of her neck merging into the first hinted curve between the lapels of the bathrobe was a pattern of magic that made murder and sudden death egregious intrusions.

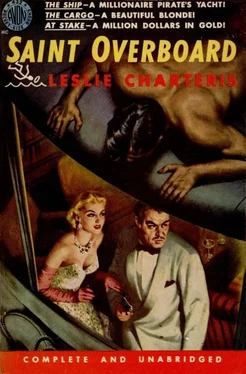

"I didn't succeed — so far. I've tried. I've even had dinner with him, and danced at the Casino. But I haven't had an invitation to go on board his boat. To-night I got the devil in me, or something. I tried to go on board without an invitation."

"Didn't you guess there'd be a watch on deck?"

"I suppose so. But I thought he'd probably be sleepy, and I could move very quietly." She grimaced. "He got me, but he let me go when I fired a shot beside his ear — I didn't hurt him — and I dived overboard."

"And thereby hangs a tale," said the Saint.

Читать дальше