The last fragment of his speech was not quite accurate. Even as he uttered it, her hand flashed to the waterproof pouch; and he looked down the muzzle of a tiny automatic that was still large enough to be an argument at point-blank range.

"You're quite right about the gun," she said, with a new glacial evenness in her voice. "And, as you say, Frenchmen have such a wonderful grip on the facts of life — haven't they? Their juries are pretty easy on a woman who shoots her lover… Don't you think you'd better change your mind?"

Simon considered this. She saw the chiselling of his handsome reckless face, the bantering lines of devil-may-care mouth and eyebrow, settle for a moment into quiet calculation, and then go back to the same irresponsible amusement.

"Anyway," he remarked, "she does give the fellow his fun first. Stay the night and shoot me after breakfast, and I won't complain."

The magnificent unfaltering audacity of him left her for a moment without words. For the first time her eyes wavered, and he read in them something that might have been an unwilling regret.

"For the last time—"

"Will I let you go."

"Yes."

"No."

"I'm sorry."

"So am I," said the Saint gently. "From the brief gander I had at Hooknose just a little while back, he looked like a man's job to me. I know you've got what it takes, but these games can get pretty tough. Tough things are my job, and I hate being jockeyed out of a good fight."

"I'm going now," she said. "I mean it. Don't think I'm afraid to shoot, because I'm ready for accidents. I'll count five while you get out of the way."

The Saint looked at her for a second, and shook his head.

"Oh, well," he said philosophically. "If you feel that way about it…"

He stood up unhurriedly. And as he stood up, one hand slid up the bulkhead with him and touched the light switch.

For the first instant the darkness in the cabin was absolute. In the sudden contrasting blackness that drenched down across her vision she lost even a silhouette of him in the opening above the companion. And then his fingers closed and tightened on her wrist like a steel tourniquet. She struggled and tripped against the couch, falling on the soft cushions; but he went down with her, and her hand went numb so that she had no power even to pull the trigger while he took the automatic away. She heard his quiet chuckle.

"I'm sorry, kid."

As they had fallen, his lips were an inch from hers. He bent his head, so that his mouth touched them. She fought him wildly, but the kiss clung against all her fighting; and then suddenly she was passive and bewildering in his arms.

Simon got up and switched on the lights.

"I'm Loretta Page," she said.

She sat wrapped in his great woolly bathrobe, sipping hot coffee and smoking one of his cigarettes. The Saint sat opposite her, with his feet up and his head tilted back on the bulkhead.

"It's a nice name," he said.

"And you?"

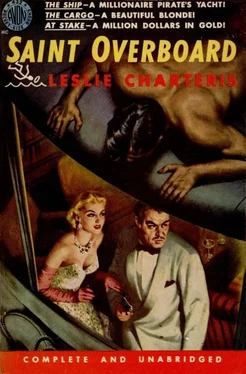

"I have dozens. Simon Templar is the only real one. Some people call me the Saint."

She looked at him with a new intentness.

"Why?"

"Because I'm so very, very respectable."

"I've read about you," she said. "But I never heard anything like that before."

He smiled.

"Perhaps it isn't true."

"There was a Professor Vargan who — got killed, wasn't there? And an attempt to blow up a royal train and start a war which went wrong."

"I believe so."

"I've heard of a revolution in South America that you had something to do with, and a plot to hijack a bullion shipment where you got in the way. Then they were looking for you in Germany about some crown jewels. I've heard that there's a Chief Inspector at Scotland Yard who'd sell his soul to pin something on you; and another one in New York who thinks you're one of the greatest things that ever happened. I've heard that there isn't a racket running that doesn't get cold shivers at the name of a certain freelance vigilante—"

"Loretta," said the Saint, "you know far too much about this life of sin."

"I ought to," she said. "I'm a detective."

The immobility of his face might have been carved in bronze, when the light-hearted mockery left it and only the buccaneer remained. In those subtle transformations she saw half his spell, and the power that must have made him what he was. There was a dance of alertness like the twinkle of a rapier blade, a veneer of flippant nonchalance cored with tempered steel, a fine humour of unscrupulousness that demoralised all conventional criterions.

And then his cigarette was back in his mouth and he was smiling at her through a haze of smoke, with blue eyes awake again and both wrists held out together.

"When arrested," he said, "the notorious scoundrel said: 'I never had a chance. My parents neglected me, and I was led astray by bad companions. The ruin of my life is due to Night Starvation.' Where are the bracelets?"

She might not have heard him. She sprang up, stretching her arms so that the sleeves of the bathrobe fell back from her wrists.

"Oh, no!.. It's too perfect. I'm glad!" The mischief was in her eyes again, matching his own, almost eclipsing it for that moment of vibrant energy. "You're telling the truth, I know. The Saint could only have been you. You would go out and take on any racket with your hands. Why didn't you tell me at once?"

"You didn't ask me," answered the Saint logically. "Besides, modesty is my long suit. The threat of publicity makes me run for miles. When I blush—"

"Listen!"

She wheeled and dropped on the berth beside him; and he listened.

"You've stolen, haven't you?"

"With discretion."

"You've tackled some big things."

"I pick up elephants and wring their necks."

"Have you ever thought of stealing millions?"

"Often," said the Saint, leaning back. "I thought of burgling the Bank of England once, but I decided it was too easy."

She stirred impatiently.

"Saint," she said earnestly, "there's one racket working to-day that steals millions. It's been running for years; and it's still running. And I don't mean any of the old things like bootlegging or kidnapping. It's a racket that goes over most of the world, wherever there's anything for it to work on; and it hits where there's no protection. I couldn't begin to guess how much money has been taken out of it since it began."

"I know, darling," said the Saint sympathetically. "But you can't do anything about it. It's quite legal. It's called income tax."

"Have you heard of the Lutine?"

He studied her with his gaze still tantalising and unsatisfied, but the eagerness of her held him more than what she was actually saying. He was discovering something between her soft-lipped beauty and her fire of anger; something that belonged equally to the lurking laughter of her eyes and the sober throb of persuasion in her voice, and yet was neither of these things; something that made all contradictions possible.

"It sank, didn't it?" he said.

"In 1799 — with about a million pounds' worth of gold on board. There've been plenty of attempts to salve the cargo, but so far the sand's been too much for them. Then the Lutina Company took over with a new idea: they were going to suck away the silt through a big conical sort of bell which was to be lowered over the wreck. It was quite a simple scheme, and there's no reason why it shouldn't have worked. The company received a few letters warning them not to go on with it, but naturally they didn't pay much attention to them."

"Well?"

"Well, they haven't tried out their sand-sucker yet. The whole thing was blown sky-high in 1933 — and the explosion wasn't an accident."

The Saint sat up slowly. In that supple movement the buffoonery slipped off him as his dressing-gown might have slipped off; and in the same transformation he was listening intently. Something like a breath of frozen feathers strolled up his spine — an instinct, a queer clairvoyance born of the years of inspired filibustering.

Читать дальше