Leslie Charteris - The Saint Overboard

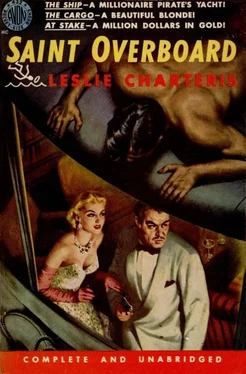

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leslie Charteris - The Saint Overboard» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1935, Издательство: Avon, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Saint Overboard

- Автор:

- Издательство:Avon

- Жанр:

- Год:1935

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Saint Overboard: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Saint Overboard»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A BEAUTIFUL BLONDE IN A BATHING SUIT who climbs on board his boat one night — under a hail of bullets!

A MILLIONAIRE PIRATE whose fortune had been made looting sunken treasure ships — operating under the noses of the salvage companies.

PLUS A strange invention which leads the Saint to a death-struggle at the bottom of the English Channel — with a fortune in gold bullion awaiting the winner!

The Saint Overboard — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Saint Overboard», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In that ghostly and fatiguing slow-motion they went down through the ship to the strong-room. It was indescribably eerie, an unforgettable experience, to trudge down the carpeted main stairway in that dark green twilight, and see tiny fish flitting between the balusters and sea-urchins creeping over a chandelier; to pick his way over scattered relics of tragedy on the floor, and see queer creatures of the sea scuttle and crawl and rocket away as his feet disturbed them; to stand in front of the strong-room door, presently, and see a limpet firmly planted beside the lock. To feel the traces of green scum on the door under his finger-tips, and remember that a hundred and twenty feet of water was piled up between him and the frontiers of human life. To see the uncouth shape of Ivaloff looming beside him, and realise that he was its twin brother — a weird, lumbering, glassy-eyed, cowled monster moving at the dictation of Simon Templar's brain…

The Saint knelt down and opened his kit of tools, and spoke into the telephone transmitter:

"I'm starting work."

Vogel was reclining in a deck chair beside the loud speaker, studying his finger-nails. He gave no answer. The slanting rays of the sun left his eyes in deep shadow and laid chalky high-lights on his cheekbones: his face was utterly sphinx-like and inscrutable. Perhaps he showed neither anxiety nor impatience because he felt none.

Arnheim had returned, clambering up from the dinghy like an ungainly bloated frog; and the three hard-faced seamen with him had hauled it up on the davits and brought it inboard before moving aft to join the knot of men at the taffrail.

Vogel had looked up briefly at his lieutenant.

"You had no trouble?"

"None."

"Good."

And he had gone back to the idle study of his finger-nails, breathing gently on them and rubbing them slowly on the palm of the opposite hand, while Arnheim rubbed a handkerchief round the inside of his collar and puffed away to a chair in the background. The single question which Vogel had asked had hardly been a question at all, it had been more of a statement challenging contradiction; his acceptance of the reply had been simply an expression of satisfaction that the statement was not contested. There was no suggestion of praise in it. His orders had been given, and there was no reason why they should have miscarried.

Loretta stared down into the half-translucent water and felt as if she was watching the inexorable march of reality turn into the cold deliberateness of nightmare. Down there in the sunless liquid silence under her eyes, under the long measured roll of that great reach of water, men were living and moving, incredibly, unnaturally, linked with the life-giving air by nothing but those fragile filaments of rubber hose which snaked over the stern; the Saint's strong lean hands, whitened with the cold and pressure, were moving deftly towards the accomplishment of their most fantastic crime. Working with skilled sure touches to lay open the most fabulous store of plunder that could ever have come in the path even of his amazing career — while his life stood helpless at the mercy of the two men who bent in monotonous alternation at the handles of the air compressor, and waited on the whim of the impassive hooknosed man who was polishing his nails in the deck chair. Working with the almost certain knowledge that his claim to life would run out at the moment when his errand was completed.

She knew… What had she told him, once? "To do your job, to keep your mouth shut, and to take the consequences"… And in her imagination she could see him now, even while he was working towards death, his blue eyes alert and absorbed, the gay fighting mouth sardonic and unafraid, as it had been while they talked so quietly and lightly in the cabin… She could smile, in the same way that he had smiled goodbye to her — a faint half-derisive half-wistful tug at the lips that wrote its own saga of courage and mocked it at the same time…

She knew he would open the strong-room; knew that he had made his choice and that he would go through with it. He would never hesitate or make excuses.

A kind of numbness had settled on her brain, an insensibility that was a taut suspension of the act of living rather than a dull anaesthesia. She had to look at her watch to pin down the leaden drag of time in bald terms of minutes and seconds. Until his voice came through the loud speaker again to announce the fulfilment of his bargain, the whole universe stood still. The Falkenberg lifted and settled in the stagnant swell, the two automatons at the air-pump bent rhymically at the wheels. Vogel rubbed his nails gently on his palms, the sun climbed fractionally down the western sky; but within her and all around her there seemed to be a crushing stillness, an unbearable quiet.

It was almost impossible to believe that only forty minutes went by before the Saint's voice came again through the loud speaker, ending the silence and the suspense with one cool steady sentence: "The strong-room is open."

3

Arnheim jumped as if he had been prodded, and got up to come waddling over. Vogel only stopped polishing his nails, and turned a switch in the telephone connection box beside him. His calm check-up went back over the line.

"Everything is all right, Ivaloff?"

"Yes. The door is open. The gold is here."

"What do you want us to send down?"

"It will take a long time to move — there is a great deal to carry. Wait…"

The loud speaker was silent. One could imagine the man twenty fathoms down, leaning against the water, working around in laboured exploration. Then the guttural voice spoke again.

"The strong-room is close to the main stairway. Above the stairway there is a glass dome. We can go up on deck again and break through the glass, and you can send down the grab. That way, it will not be so long. But we cannot stay down here more than a few minutes. We have been here three quarters of an hour already, which is too long for this depth."

Vogel considered this for a moment.

"Break down the glass first, and then we will bring you up," he directed, and turned to the men who were standing around by the winch. "Calvieri — Orbel — you will get ready to go down as soon as these two come up. Grondin, you will attend to the grab—"

For some minutes he was issuing detailed orders, allotting duties in his cold curt voice with impersonal efficiency. He shook off the lassitude in which he had been waiting without losing a fraction of the dispassionate calm which laid its terrifying detachment on everything he did. He became a mere organising brain, motionless and almost disembodied himself, lashing the cogs of his machine to disciplined movement.

And as he finished, Ivaloff's voice came through again.

"We have made a large enough opening in the dome. Now we should come up."

Vogel nodded, and a man stepped to the controls of the winch. And at last Vogel got up.

He got up, straightening his trousers and settling his jacket with the languid finickiness of a man who has nothing much to do and nothing of importance on his mind. And as casually and expressionlessly as the same man might have wandered towards an ashtray to dispose of an unconsidered cigarette-end, he strolled over the yard or two that separated him from the air pump, and bent over one of the rubber tubes.

His approach was so placid and unemotional that for a moment even Loretta, with her eyes riveted mutely on him, could not quite believe what she was seeing. Only for a moment she stared at him, wondering, unbelieving. And then, beyond any doubt, she knew…

Her eyes widened in a kind of blind horror. Why, she could never have said. She had seen death before, had faced it herself only a little while ago, had lived with it; had stood pale and silent on that same deck while Professor Yule died. But not until then had she felt the same frozen clutch on her heart, the same dumb stab of anguish, the same reckless annihilation of her restraint. She didn't know what she was doing, didn't think, made no conscious movement; and yet suddenly, somehow, in another instant of time, she was beside Vogel, grasping his wrist and arm, tearing his hand away. She heard someone sobbing: "No! No! Not that!" — and realised in a dazed sort of way that she was hearing her own voice.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Saint Overboard»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Saint Overboard» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Saint Overboard» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.