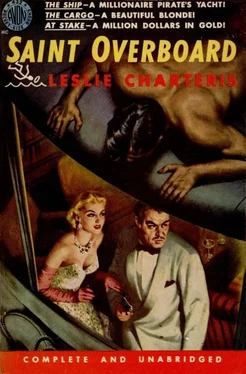

Leslie Charteris - The Saint Overboard

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leslie Charteris - The Saint Overboard» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1935, Издательство: Avon, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Saint Overboard

- Автор:

- Издательство:Avon

- Жанр:

- Год:1935

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Saint Overboard: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Saint Overboard»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A BEAUTIFUL BLONDE IN A BATHING SUIT who climbs on board his boat one night — under a hail of bullets!

A MILLIONAIRE PIRATE whose fortune had been made looting sunken treasure ships — operating under the noses of the salvage companies.

PLUS A strange invention which leads the Saint to a death-struggle at the bottom of the English Channel — with a fortune in gold bullion awaiting the winner!

The Saint Overboard — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Saint Overboard», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"So you signed on the dotted line, Simon," she said softly.

"Didn't you always know I would?"

"I hoped you would."

"It's been worth it."

She turned her face a little. Presently she said: "I told you I was afraid, once. Do you remember?"

"Are you afraid now?" he asked, and felt the shake of her head.

"Not now."

He kissed her. Her lips were soft and surrendering against his. He held her face in his hands, touched her hair and her eyes, as he had done in the garden.

"Will you always remember me like this?" she said.

"Always."

"I think they're coming."

A key turned in the lock, and he stood up. Vogel came in first, with his right hand still in his side pocket, and two of his crew framed themselves in the doorway behind him. He bowed faintly to the saint, with his smooth face passive and expectant and the great hook of his nose thrust forward. If he was enjoying his triumph of scheming and counter-plot, the exultation was held in the same iron restraint as all his emotions. His black eyes remained cold and expressionless.

"Have you made up your mind?" he asked.

Simon Templar nodded. In so many ways he was content.

"I'm ready when you are," he said.

2

They were settling the forty-pound lead weights over his shoulders, one on his back and one on his chest. He was already encased in the heavy rubber-lined twill overall, which covered him completely from foot to neck, with the vulcanised rubber cuffs adjusted on his wrists and the tinned copper corselet in position; and the weighted boots, each of them turning the scale at sixteen pounds, had been strapped on his feet. Another member of the crew, similarly clad, was explaining the working of the air outlet valve to him before the helmet was put on.

"If you screw up the valve you keep the air in the dress and so you float. If you unscrew it you let out the air, and you sink. When you get to the bottom, you adjust the valve so that you are comfortable. You keep enough air to balance the weights without lifting you off your feet, until it is time to come up. You understand?"

"You have a gift for putting things plainly," said the Saint.

The man grunted and stepped back; and Kurt Vogel stood in front of him.

"Ivaloff will go down with you — in case you should be tempted to forget your position," he explained. "He will also lead you, to the strong-room, which I have shown him on the plans of the ship. He will also carry the underwater hydro-oxygen torch, which will cut through one and a half inches of solid steel — to be used as and when you direct him."

Simon nodded, and drew at the cigarette he was smoking. He fingered an instrument from the kit which he had been examining.

"Those are the tools of the man you killed," said Vogel. "He worked well with them. If there is anything else you need, we will try to supply you."

"This looks like a pretty adequate outfit."

Simon dropped the implement back in the bag from which he had taken it. The brilliance of the afternoon had passed its height, and the sea was like oiled crystal under the lowering sun. The sun was still bright, but it had lost its heat. A few streaks of cloud were drawing long streamers towards the west.

The Saint was looking at the scene more than at Vogel. There was a dry satirical whim in him to remember it — if memory went on to the twilight where he was going. Death in the afternoon. He had seen it so often, and now he had chosen it for himself. There was no fear in him; only a certain cynical peace. It was his one regret that Vogel had brought Loretta out on to the deck with him. He would rather have been spared that last reminder.

"I shall be in communication with both of you by telephone all the time, and I shall expect you to keep me informed of your progress." Vogel was completing his instructions, in his invariable toneless voice, as if he were dealing with some ordinary matter of business. "As soon as you have opened the strong-room, you will help Ivaloff to bring out the gold and load it on to the tackle which will be sent down to you… I think that is all?"

He looked at the Saint inquiringly; and Simon shrugged.

"It's enough to be going on with," he said; and Vogel stood aside and signed to the man who waited beside him with the helmet.

The heavy casque was put over the Saint's head, settled in the segmental neck rings on the corselet, and secured with a one-eighth turn; after which a catch on the back locked it against accidental unscrewing. Through the plate-glass window in the front Simon watched the same process being performed on Ivaloff, and saw two seamen take the handles of the reciprocating air pump which had been brought out on deck. His breathing became tainted with a faint odour of oil and rubber…

"Can you hear me?"

It was Vogel's voice, reverberating metallically through the telephone.

"Okay," answered the Saint mechanically, and heard his own voice booming hollowly in his ears.

Ivaloff beckoned to him; and he stood up and walked clumsily to the stern. A section of the taffrail had been removed to give them a clear passage, and a sort of flat cradle had been slung from the end of the boom from which the bathystol had been lowered. They stepped on to it and grasped the ropes, and in another moment they were swinging clear of the deck and coming down over the water.

Taking his last look round as they went down, Simon caught sight of the outboard coming back, a speck creeping over the sea from the north-west; and he watched it with an arctic stillness in his eyes. So, doubtless, the lighthouse had been dealt with, and two more innocent men had gone down perplexedly into the shadows, not knowing why they died. Before long, probably, he would be able to tell them…

Then the water closed over his window, and, as it closed, seemed to change startlingly from pale limpid blue to green. In an instant all the light and warmth of the world were blotted out, leaving nothing but that dim emerald phosphorescence. Looking up, he could see the surface of the water like a ceiling of liquid glass rolling and wrinkling in long slow undulations, but none of the crisp warm sparkle which played over it under the sun came through into the weird viridescent gloaming through which they were sinking down. Up over his head he could see the keel of the Falkenberg glued in bizarre truncation to that fluid awning, the outlines growing vaguer and darker as it receded.

They were sinking through deeper and deeper shades of green into an olive-green semi-darkness. There was a thin slight singing in his ears, an impression of deafness: he swallowed, closing his nasal passages, exactly as he would have done in coming down in an aeroplane from a height, and his ear-drums plopped back to normal. A long spar rose out of the green gloom to meet them, and he realised suddenly that it was a mast: he looked down and saw the dim shapes of the funnels rising after it, slipping by… the white paintwork of the upper decks.

The grating on which they stood jarred against the rail of the promenade deck, and their descent ceased. Ivaloff was clambering down over the rail, and Simon followed him. In spite of all the weight of his gear, he felt curiously light and buoyant — almost uncomfortably so. Each time he moved he felt as if his whole body might rise up and float airily away.

"Unscrew your valve."

Ivaloff's gruff voice cracked in his helmet, and he realised that the telephone wiring connected them together as well as keeping them in communication with the Falkenberg. Simon obeyed the instruction, and felt the pressure of water creeping up his chest as the suit deflated, until Ivaloff tapped on his helmet and told him to stop.

The feeling of excessive buoyancy disappeared with the reduction of the air. As they moved on, he found that the weights with which he was loaded just balanced the buoyancy of his body, so that he was not conscious of walking under a load; and the air inside his helmet was just sufficient to relieve his shoulders of the burden of the heavy corselet. Overcoming the resistance of the water itself was the only labour of movement, and that was rather like wading through treacle.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Saint Overboard»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Saint Overboard» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Saint Overboard» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.