“Try again, smart boy. Parker’s dead.”

“I know it. But I couldn’t rest easy till I paid you the twenty bucks.”

The line hummed in his ear for a few seconds, and then she said, “Is it really Parker?”

“I told you it was.”

“But — I saw Lynn in Stern’s, three, four months ago. She said you was dead.”

“She thought I was. I want to talk to you.”

“You’re lucky,” she said. “This is my monthly vacation. 298 West 65th — the name is by the bell downstairs.”

“I’ll be right there.”

“Wait. Let me talk to the bartender again. I’m supposed to tell him whether you’re straight or not.”

“Sure.”

He went out of the phone booth, and it suddenly seemed a lot cooler in the bar. He caught Bernie’s eye, and motioned at the phone. “She wants to talk to you again.”

Bernie nodded and came back down the bar. On the way by he said, “Stick around a minute, huh?”

Parker nodded. Two guys down at the end of the bar by the door were definitely not looking at him.

Bernie talked briefly on the phone, then hung up and came back. A smile worked its way lugubriously up out of his gut, fading away when it reached his face. “Okay, friend,” he said. “Glad I could help you.”

“Thanks again,” said Parker. He got off the stool and headed for the door. The two guys at the end of the bar looked at him now.

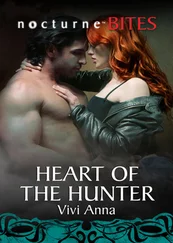

She hadn’t changed. She still looked seventeen, though by now she must be pushing thirty-five. Her smallness helped; she was barely five feet tall and delicately boned. Her eyes were large and round and green, her hair was flaming red, her rosebud mouth was a carmine blossom against a pale clear complexion.

Her body was beautifully proportioned for her size, with conical well-separated breasts, a fragile waist, low-slung hips. Only her speech gave her away: it was not the speech of a college freshman.

She flung open the door, wearing a swirling muumuu with at least ten colors on it, and cried, “Come on in here, you lovely bastard — let me welcome you back to life.”

He nodded, and brushed past her through the foyer and down the two steps into a huge movie set of a living room. Porcelain figures, mostly of frogs, crammed all the table tops.

“Surly Parker,” she said, closing the door and coming down the steps after him. “You’re the same as ever.”

“So are you. I want to ask you a favor.”

“I thought you were my long lost brother. Sit down. What are you drinking?”

“I’ll take a beer.”

“I’ve got vodka.”

“Beer.”

“Oh well, the hell with it. I should have known better. Parker doesn’t make social calls. You don’t have to have the beer if you don’t want it.”

“Good,” he said. He sat down on the sofa. “You look good.”

She sat on the leather chair facing him, flouncing into it, one leg dangling over the arm. “Small talk was never your forte,” she said. “Go ahead and ask your favor.”

“You know a guy named Mal Resnick?”

She hunched her shoulders, bit the corner of her lower lip, stared sideways at a fringed lampshade. “Resnick,” she said, the name coming out muffled because her teeth still held the corner of her lip. “Resnick.” Then she shook her head and bounced to her feet. “Nope, it doesn’t ring a bell. Was he one of our crowd? Should I know him from the coast?”

“No, from here in New York. He’s in the syndicate some-where.”

“The Outfit , baby. We don’t say syndicate any more. It’s square.”

“I don’t care what you call it.”

“Anyway — oh.” Her eyes widened and she stared at the ceiling. “Oh! That bastard!”

“You know him?”

“No, of him. One of the girls was bitching to me. He got her for an all night — it was supposed to be fifty bucks. There was only thirty-five in the envelope. She complained to Irma, and Irma told her there was no sense raising a stink about it, he was in the Outfit. She said he was lousy anyway. All grunts and groans, no real action.”

Parker leaned forward, elbows on knees, and cracked his knuckles. “You can find out where he is?”

“I suppose he’s at the Outfit,” she said.

“What’s that, some kind of club?”

“No, the hotel.” She started to say more, then suddenly swirled around, reaching for a carved silver box on the teakwood table. She flipped it open, withdrew a cigarette with a rose red filter, and picked up a heavy silver Grecian-style lighter.

Parker watched her, waiting till she had the cigarette lit before he said, “Okay, Wanda, what is it?”

“Call me Rose, will you, dear? I’m out of the habit of answering to the other.”

“What is it?”

She looked at him a moment, thoughtfully, cigarette smoke misting around her face. Then she nodded and said, “We’re friends, Parker. I suppose we’re friends, if either one of us could be said to have friends.”

“That’s why I came to you.”

“Sure. The loyalty of friendship. But I’m an employee, too, Parker. In a business where it pays to have loyalty to the company. And the company wouldn’t like me to tell anybody about the Outfit hotel.”

“So you didn’t tell me a thing.” He cracked his knuckles impatiently. “You know that already, why talk about it?”

“How strong are you, Parker?” She turned away and walked across the room to the draped windows, talking over her shoulder as she went. “I’ve often wondered about that. I think you’re the strongest man I’ve ever met.” She stopped and looked back at him, one hand on the drapes. “But I wonder if that’s enough.”

“Enough for what?”

She pulled the drape to one side. The window was tall and wide. She stood framed against it, looking out, tiny and shapely. “You want an Outfit man named Resnick,” she said. “If I know you, you want him for something he won’t like.”

“I’m going to kill him,” Parker said.

She smiled, nodding. “There,” she said. “That’s something he won’t like. But what if something goes wrong, and you get grabbed, and they ask you where you found out about the hotel? If they ask you hard?”

“I got it from a guy named Stegman.”

“Oh? What you got against Stegman?”

“Nothing, it’s just believable. Why, do you know him?”

“No.” She slid the drapes shut again, prowled the room some more, crossing to the opposite side merely to flick ashes into a blue seashell. “All right,” she said, “you wait here. I’ll make a phone call. I want to know for sure whether that’s where he is or not.”

“Fine.”

“If you want a beer after all,” she said, “the kitchen is that way.”

She left the room, and he killed time by lighting a cigarette. Then he picked up a green porcelain frog from the nearest table and looked at it. It gleamed and its eyes were black. He turned it over and it was hollow, with a round hole in the bottom, and the words Made in Japan impressed in the porcelain next to the hole. He put the frog back and looked around at the room. She was doing all right these days.

She came back and said, “He’s there. I even got the room number.”

“Fine,” he said, getting to his feet.

She smiled, with a trace of sourness. “You aren’t a guy for small talk,” she said. “Get what you want, and go.”

“One thing at a time,” he said, “that’s all I can think about. Maybe I’ll come back and see you later?”

“The hell you will. Here, I wrote it down.”

He took the paper from her and read her small careful script — Oakwood Arms, Park Avenue and 57th Street. Suite 361. He read it three times, then crumpled the paper and dropped it into a free-form glass ashtray. “Thanks.”

Читать дальше