“And your wife knew about the book?” Sellitto asked.

“I guess I mentioned the project to her and that I was reading it. She’s been in my apartment off and on over the past year. She must’ve stolen it sometime when she was over.” He regarded Rhyme. “But why didn’t you think I was the one, like she planned?”

Rhyme said, “I did at first. But then I decided it wouldn’t’ve been smart for somebody to use a book that could be traced to them as a template for murder. But it’d be very smart for someone else to use that book. And whoever put this together was brilliant.”

“He profiled you,” Sachs said with a smile.

Rhyme grimaced.

Sellitto had then spoken to Ferguson and learned of the nasty divorce, which gave them the idea that his ex might be behind it. They learned, too, that he’d just dropped off Vicki Sellick, the woman he was dating, at her apartment.

They’d tried to call the woman but, when she hadn’t picked up, Sachs and the team had sped there to see if she was in fact under attack.

“She was nuts,” Ferguson muttered. “Insane.”

“Ah, madness and brilliance — they’re not mutually exclusive,” Rhyme replied. “I think we can agree on that.”

Then Marko rubbed his close-cropped head and laughed. “I’m sort of surprised you didn’t suspect me. I mean, think about it. I was first on the scene at the Twenty-sixth Street homicide, I knew forensics, I’d taken your course and you could assume I’d read your book.”

Rhyme grunted. “Well, sorry to say, Kid, but you were a suspect. The first one.”

“Me?”

“Sure. For the reasons you just mentioned.”

Sellitto said, “But Linc had me check you out. You were in the lab in Queens, working late, when the first vic was killed.”

“We had to check. No offense,” Rhyme said.

“It’s cool, sir… Lincoln.”

“All right,” Sellitto muttered. “I got paperwork to do.” He left with Ferguson, who would go downtown to dictate his statement. Marko, too, left for the night.

“That his first name or last?” Rhyme asked.

“Don’t know,” Sachs replied.

An hour later, she’d finished bundling up the last of the evidence collection bags and jars and boxes for transport to the evidence storage facility in Queens.

“We’ll definitely need to air the place out,” Rhyme muttered. “Smells like an alleyway in here.”

Sachs agreed. She flung open the windows and poured them each a Glenmorangie scotch. She dropped into the rattan chair beside Rhyme’s Storm Arrow. His drink was in a tumbler, sprouting a straw. She placed it in a cup holder near his mouth. He had good movement of his right arm and hand, thanks to the surgery, but he was still learning the subtleties of control and didn’t want to risk spilling valuable single-malt.

“So,” she said, regarding him with a gleam in her eye.

“You’re looking coy, Sachs.”

“Well, I was just thinking. Are you finally going to admit that there’s more to policing than physical evidence?”

Rhyme thought for a moment. “No, I don’t think so.”

She laughed. “Rhyme, we closed this one because of deductions from witness statements and observations… and a little profiling. Evidence didn’t have anything to do with it.”

“Ah,” Rhyme said, “but there’s a flaw in your logic, Sachs.”

“Which is?”

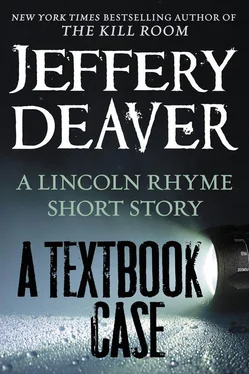

“Those deductions and observations all came from the fact that somebody bought a textbook of mine, correct?”

“True.”

“And what was the book about?”

She shrugged. “Evidence.”

“Ergo, physical evidence was the basis for closing the case.”

“You’re not going to concede this one, are you, Rhyme?”

“Do I ever?” he asked and, placing his hand on hers, enjoyed a long sip of the smoky liquor.