Which Snitch had been doing for perhaps ten minutes now, complaining bitterly about her flagrant carryings-on with the Pokerino barker and continually asking, “Is it fair? Mr. Garbugli?”

“As long as she remains unmarried,” Garbugli said, “she’s entitled to the alimony payments awarded to her.”

“But she’s living with this big Texan,” Snitch protested.

“It wouldn’t matter if she was living with the Seven Dwarfs,” Garbugli said. “You’d still have to pay her.”

“I won’t pay,” Snitch said.

“In which case you’ll go to jail. And while you’re in jail, she’ll continue her arrangement with this here Pokerino barker. You want my advice? Pay.”

“It’s not fair,” Snitch said.

“My good friend,” Garbugli said, “there is much on this road of life that is unfair, but we must all carry our share of the goddamn burden.”

“Mr. Garbugli?” Snitch said.

“Yes?”

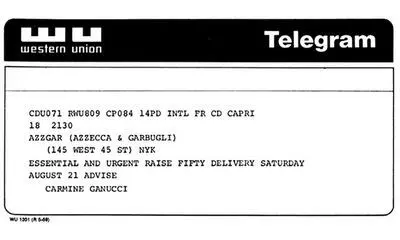

The telephone buzzed. “Excuse me,” Garbugli said, and lifted the receiver. “Vito Garbugli speaking,” he said. “What? Oh, certainly, I’ll be right in, Mario.” He rose swiftly and walked around his desk. “My partner. I’ll just be a moment,” he said, and went to the door separating his office from Azzecca’s. The door closed behind him. Snitch sat in the leather armchair thinking about how unfair it was. He sat that way for perhaps five minutes. He was beginning to think Garbugli would not return; that wasn’t fair either. The door to the outer office opened, and a long-legged, pretty redhead wearing a short beige skirt and a green blouse entered, walked quickly to Garbugli’s desk, put a yellow sheet of paper on it, swiveled, smiled at Snitch, walked to the door again, and went out. The office was silent. Snitch got up and walked to the windows. On the street below, decent men like himself were going their merry way without having to worry about paying alimony to a bitch who was living with a big Texan who rolled his own cigarettes. Seven Dwarfs, some sense of humor the counselor had. Snitch glanced at the yellow sheet of paper the girl had put on Garbugli’s desk. It looked very much like a telegram or something. Merely out of curiosity, Snitch began to read it:

Sure, Snitch thought, Ganooch sends telegrams all the way from Italy, and guys in the street go their merry way, while I have to pay alimony to somebody I hardly even met — I was only married to her, for Christ’s sake, for sixteen lousy months! He sat in the leather chair again. At the window, the air conditioner hummed serenely. In a little while, he fell asleep.

When Garbugli came back into the office, he found his client snoring. He also found the cable from Carmine Ganucci. He quickly stuffed it into his pocket, shook Snitch by the shoulder, and asked him if there was anything else he wished to discuss. Snitch had difficulty coming awake and for one terrifying moment relived a time in Chicago when he had been shaken from sleep in the middle of a February night and asked why he had such a big mouth. He had answered, “ Who has a big mouth?” and someone in the dark had said, “ You have a big mouth,” and Snitch had said, “Aw, come on, I do not.” He established his surroundings now, assured Garbugli he had nothing more to ask (but that he wasn’t ready to pay any alimony to no whore, neither), thanked the lawyer for his time, and left. At the desk outside, he bummed a cigarette from the redhead who had brought the cable in, and then went down to the street.

It was going to be a hot day.

He wondered if it was this hot in Italy. Probably not. He also wondered why it was ESSENTIAL AND URGENT that Carmine Ganucci RAISE FIFTY. Fifty what ? Not measly dollars, that was for sure. Ganooch probably carried around ten times that amount just in case he had to tip a cabbie. Could it be fifty thousand ? Was it essential and urgent that Ganooch raise fifty thousand by Saturday? That was a lot of money. People did not trip across fifty thousand dollars in the gutter every day. Nor did Ganooch’s trusted governess come around every day asking about various and sundry felonies perpetrated on a Tuesday night.

Something was in the wind.

Snitch sensed this with the same rising excitement he had known in Chicago on February 14, 1929. He could barely refrain from dancing a little buck and wing right there on Forty-fifth Street. Something was in the wind, all right, something really big. And Snitch knew just the party who would love to hear all about it.

If he hadn’t been temporarily broke, he’d have taken a taxi uptown.

In the office upstairs, Mario Azzecca and Vito Garbugli were conducting an intense examination. Or rather, Azzecca was conducting the examination; Garbugli mostly listened. Azzecca’s witness was Marie Pupattola, the long-legged, redheaded secretary who had brought the cable into his partner’s office and put it on his desk. Marie was a bit frightened by the intensity of Azzecca’s questions. Also, she had just got her period yesterday.

“Was he asleep when you came in here?” Azzecca asked.

“Gee, I don’t remember,” Marie said.

“Try to remember!” he said. “Was he asleep in that chair when you brought the cable in?”

“Now, now, Counselor,” Garbugli said.

“I don’t remember,” Marie said, knowing full well that Snitch had not been asleep because she had very definitely smiled at him, and she was not in the habit of smiling at people who were asleep.

“Were his eyes closed?”

“They could have been.”

“Were they closed, or were they open?”

“Sometimes,” Marie said, “when a person’s eyes are closed, they could also look open.”

“Did his look open or closed?”

“They looked closed,” she said, which was a lie because they had looked very open, especially when she’d smiled at him.

“Then do you think he was asleep?”

“He could have been asleep,” she said, “but gee, I don’t remember.”

“Do you think he saw this cable, Marie?”

“Gee, I don’t know,” Marie said. “Why would he have seen it?”

“Because you put it on the desk there, and he was right here in this room alone with it for Christ knows how many minutes.”

“Now, now, Counselor,” Garbugli said.

“ Would he have looked at it?” Marie said. “I mean, if he was asleep?”

“ Was he asleep?”

“He was very definitely asleep,” she said.

“Are you sure?”

“I know a man when he’s asleep or not, don’t I?” she asked.

“Thank you, Marie,” Garbugli said.

“Not at all,” Marie said, and smiled at him the same way she had smiled at Snitch, and then went out to her desk.

“What do you think?” Garbugli said.

“I think she’s a lying little twat, and that Snitch was awake with both eyes open, and that he read every word of that cable,” Azzecca said.

“So do I,” Garbugli said. “I think we had maybe better call Nonaka and ask him to look up our friend Snitch Delatore.”

“Nonaka gives me the shivers,” Azzecca said. “Besides, first things first. What do we do about this money Ganooch wants?”

“Send it,” Garbugli said.

“Why do you suppose he needs that kind of money by Saturday?”

“I don’t know,” Garbugli said. “But if he cabled all the way from Capri, then it must be pretty...”

“ If it was him who sent the cable,” Azzecca said shrewdly.

“It’s signed Carmine Ganucci, Counselor.”

“That’s not a signature,” Azzecca said. “That’s just a cable with the words ‘Carmine Ganucci’ on it. It could have been twelve different people who sent that cable. It could even be the police who sent that cable.”

Читать дальше