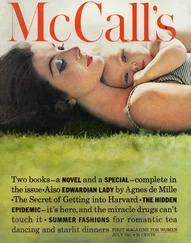

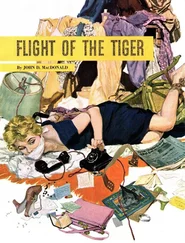

Yes, this Harkinson was one of the great broads, years past the peak of it, but hanging in there so well, you had to marvel at what it had to be costing her in time and effort to keep the illusion of youth. Not only the masks and packs, and the oils and skin foods and lotions and the careful measuring of sun to keep that flawless brown gold of the expensive tennis-club tan, but on top of that, the daily measurements of every dimension to the quarter part of an inch, followed by exercises that would exhaust a stevedore. Then, once you had the pretty machine all assembled, you had to imitate the unconscious tricks of youth, no matter how tired the flesh. You had to walk pert, more trimly and quickly, smile saucy, exaggerate all expressions and all gestures, move the head quickly, and run the voice up and down as many notes of the scale as you could handle.

But, baby, the years are written on the backs of your hands, in bulged veins and thickened knucklebones, and written in the horizontal lines across your throat and in the little striated patterns on the slightly puffed flesh under the eyes.

She’d use every possible way to keep the machine going, from pep pills to those long, hearty romps in the sack at regular intervals to keep the girl-making glands humming.

She was obviously ready to go out. She wore a little beige dress in a linen weave, very unadorned, very simple, yet fitted so artfully and elegantly to that brick-house build the price tag almost showed. And elegance in the careful-casual tossle of the sun-streaked hair, sheen of nylons on the very special legs, a couple of expensive ounces of high-heeled sandals, white purse by the door with white gloves on it, and on the table beside the purse, one of those bright little hats they pull on to keep their hair from snapping around when they drive their convertibles.

There was a business with the eyes she did very well indeed, swinging the glance away slowly and then popping it back onto you, like being snapped with a little whip. Broad across the brows, heavy and prominent bones in the cheeks. Nose a little small, upsnubbed over a short upper lip. Lips of equal unusual heaviness in a considerable amount of mouth.

So there she was, one long arm away, all fresh and fragrant and resilient, unable to make any motion without effective and graceful display of a promise of goodies for me and thee, eyes making her cool speculations the way the man-smart ones can’t help doing, while the mouth made the words of another kind of conversation.

If something like this, Barney thought, really vectored in on that sailboat kid, it would be like going after a goldfish by sticking a twelve-gauge into the fish bowl and pulling both triggers.

“Well — if it is something really important,” she said. “I’m waiting for them to bring my car around. It’s been in the garage since Saturday morning. I have an appointment with the hairdresser, and then I was going to go...”

“We’re asking you to do a favor, or maybe more like a citizen’s duty,” Kindler said. “What we’ve got to get is a positive identification on a body.”

She put her fingertips to her throat and made her eyes round and sat on the broad arm of a low chair. It pulled the hem of the short little dress about four inches above her knees.

“My God, who is it?”

“We’re pretty sure he’s a fellow worked for you, Mrs. Harkinson. Staniker. Captain Garry Staniker. We can’t locate any next of kin.”

“Automobile accident?”

“No. What he did, he killed himself. He was holed up in a fleabag over near Coral Gables and he got loaded and sat in the bathtub and cut his wrists. What it looks like, he got depressed over the bad luck on that cruise, and getting burned and being the only one got out of it.”

She swallowed with an apparent effort and said, “I’m not going to be a hypocrite and tell you this is any horrid shock, men. Garry wasn’t one of my favorite people.” She shook her head and gave them a wry, disarming grin. “While he was still running my boat, he seemed like a nice guy. And really attractive in a kind of outdoorsy way. When — a very dear and close friend of mine passed away, I was very alone. And Garry was very sweet and understanding.” She stood up with a lithe quickness, made a little shrug, and a mouth of distaste. “But he tried to keep hanging on. Male pride, I suppose. Some men won’t admit it when something is over. He got to be a damned tiresome bore. He couldn’t get a good job. He’d come by and drink and tell me his problems and get mean drunk. It was a relief when he finally got a decent boat to run and took off.”

As she turned away, Barney Scheff read Bert Kindler’s quick glance. They had been teamed for five years. All the people they worked on fell into some familiar category. Approach had to be adjusted to the individuals. Staying in any pattern was a sure way to come up empty oftener than you should. You developed a feeling, like an extra sense of smell. Like with that Raoul Kelly, they shared the decision to play it his way, but had one of them been dubious, they would not have gone along. The weirds were easy to smell out, as easy as the chronic losers. Amateurs could be suckered by traps so old you had to brush off the cobwebs before you used them. But the cute ones took you onto uneasy ground, especially when they were intelligent and confident. A clumsy truth and a plausible lie could sound almost alike. The frankness of her implication of an intimacy between her and Staniker could be either because the news he was dead had shaken her up, or because she was one of those women who got a little bit of jolly out of letting practically anybody know that if the stars were right it was possible to get a hack at all that merchandise, or because she sensed there was a chance it would be checked out later, and if they came up with a relationship she had not implied in any way, they would wonder why she hadn’t.

Kindler’s glance said, “My turn” and Scheff’s slight shrug said, “Have fun.”

“I guess losing that boat and those people would give him some new problems to tell you, Mrs. Harkinson.”

She spun toward him, head a-tilt, and said, “Do you ever get a funny kind of superstition about people? I mean somebody is all right, and then they sort of turn into a loser, and everything starts to go wrong for them. You get the sort of spooky feeling you don’t want them anywhere near you. As if it could rub off and they could turn you into a loser too.”

“I know what you mean,” Kindler said.

“He wanted to tell me his problems all right,” she said grimly. “He phoned me as soon as he rented that place last Friday. He was going to come right out. I told him I’d made it very damned clear back in April we were all through. He said he was going to come and see me anyway and if I tried to keep him from coming here, he’d — give me a thumping I’d remember a long time. Garry was a brutal man, Sergeant. And I couldn’t afford to let him know I was scared of him. But I was. I’ve been terrified he’d force his way in here. So — I can’t be sorry he’s dead. But — there’s something funny about it.”

“Like what?”

“I wouldn’t say he was the kind of human being who’d brood about losing that boat and those people. He’d worry about not being able to find a job. But on the phone he didn’t seem depressed at all. Just kind of arrogant. He told me he had a big check in advance for an exclusive story on the whole thing. I don’t know how to say this — just that if he had money in his pocket, he felt good. And he just wasn’t sensitive — the way I guess people are who commit suicide.”

“Well,” said Kindler, “to get back to the point here, we’d like for you to come on in and take a look, just for the record. A formality.” She stood hip-shot, elbow resting in her palm, chin against her thumb, looking broodingly at the floor. “I want to do the right thing. And you have been nice about this, both of you. Please understand. I know it’s only a formality, really, but it wouldn’t be just a formality to me. It would be a very personal thing. And it would be like — confirming that something still exists that died a long time ago.”

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)