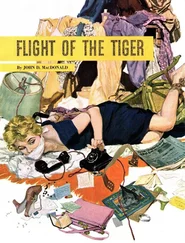

Oliver Akard was in the empty house of his parents in the empty afternoon. Dust motes winked in the shafts of sunshine. His father was working overtime at the shop. His mother was at a Saturday afternoon benefit bridge.

He had slept so late she was gone by the time he got up. It had been a relief not to have to face that martyred, wounded look, the audible signs of affliction. It had been almost dawn when he had come home, and on an impulse to challenge them, instead of turning off the engine and coasting into the driveway, he had driven in, parked in his usual place beyond the carport, revved the engine three times, the holes rusted through the muffler adding a snare-drum resonance to the insult to the neighborhood peace.

An hour after his late breakfast he was hungry again, made two thick sandwiches of peanut butter and drank most of a quart of milk, drinking it from the cardboard package as he watched television baseball. The game seemed meaningless, and he could find nothing on the other channels to hold his interest. He left it turned on, and soon the sour soundtrack and dramatic voices of an old movie eased the silence of the house.

He had packed a dufflebag with most of what he would need, and put it in the back of his closet behind his winter coat. He could put the toilet articles in at the last moment. He had composed the note he would leave and had hidden it in his desk. Crissy had helped him with it:

I have to go away alone for a couple of weeks to think things out. Nothing has been going right any more. I’m sorry for all the worry I’ve given you lately. I have some money. I have to get things straightened out in my head before I do something real crazy .

Your Son, Oliver

Crissy was certainly fussy about having things exactly right. She thought one word ought to be changed and she wouldn’t let him cross it out. He had to write the whole thing out again.

He felt irritated with her, the way she had acted as if he wouldn’t be able to remember things from one minute to the next. She had made him draw the floor plan from memory, even to putting in the street and the little box to indicate where he would park, and a dotted line to the bungalow door. Number 10. Mooney Bungalow Courts. And he had to write out that little list of what to bring with him.

When he had tried to protest, she had leaned her face into his, her eyes startlingly round and bright. Her voice had been very slow and distinct, her mouth shaping each word as though for a deaf person, and she had put in some words which had shocked him. He had not known she could come on so heavy.

She had told him not to come by until dusk. He planned to leave the house well before that, so he would be gone before either of them came home. The hands of the house clocks moved with a terrible slowness. Yet when he would realize that another hour had gone by, and he was an hour closer to what they were going to do, the bottom seemed to fall out of his stomach. It was better to think beyond that part of it, and think about going away with her. Perhaps in a week, she said. That’s why the note said he was going alone. So they wouldn’t come after him to get him away from this terrible, terrible woman.

Going away with her would be the reward for doing what he had to do tomorrow night. She wouldn’t tell him where. She said it had to be a surprise. He would adore it. A lovely, lovely place. Long, lazy days and nights of love.

He went back to the kitchen and opened the refrigerator, and as he reached to get the milk carton and finish it, he caught a faint scent of fresh limes, and it made his heart stand still. The shampoo she used had that lime scent, familiar now from all the times of breathing her in, face in that softness and crispness of her hair. There was one perfume she wore only for bed, a strange heavy bitter-sweet muskiness that seemed to put a sharper and more desperate edge on his need. And there was often the faint odor of rum and oranges in the hot gasping moisture of her breath against his face, and under these mingled smells, another one, the elusive, distinctive scent of herself, of her flesh and of the using of the flesh. Sometimes when it had just ended and she rested in his arms, these richnesses seemed almost unpleasant, and would remind him of the times when he was tiring and she was still demanding, how fleshy and vast she would seem to become in the bed’s darknesses, something so remorseless and devouring it would seem to him, in that half delirium of fading response, that some animal thing was after him, grasping, straining, grunting, churning at his helplessness.

He could look at her later at a distance, dressed, so slender and tidy and graceful, and marvel that the night-thing could be so completely hidden away, all the soft machinery dismantled and dispersed.

He walked through the house, touching things. This table. This hassock. These white bricks in the fireplace wall.

Raoul had taken Francisca to the beach Saturday afternoon, all the way up to North Miami Beach. Commitment had created small tensions between them. They talked too rapidly and gayly about nothing, and lapsed often into silences which were not comfortable. He had the curious sensation that he was taking pictures of her, a mechanism in the back of his mind clicking, filing a color print away. When she swam alone and then came smiling up the little slope of beach toward him, yanking the swim cap off, shaking out her dark hair, pelvis tilting in her slightly self-conscious stride in her brief, one-piece, candy-striped suit, scissoring thighs in the flawless even dusky gold of ancient ivory, the camera clicked again and again.

When she lowered herself to the big beach towel beside him, the camera in his mind backed away from the two of them and took the incongruity of that lithe elegance in the gross company of such a squat broad hairy fellow with a pocked peasant face, hair thinning. Then the camera took closeups of her beside him, droplets of sea water on her bare shoulder, and an oblique glance of her dark eyes before she looked toward the sea, her profile perfect as new coins against the beach glare, against the background of all the beach people stretching into the distance along the broad band of whiteness bordering the cobalt blue water with its dancing mirror glints.

It disturbed him to have the camera-feeling, as if he were storing up the memories of her for the empty years ahead. He and Sam Boylston had debated how much danger she might be in. It had to be weighed against the danger of destroying the adjustment she had achieved. It was her hiding place, and were it destroyed, she might seek that other hiding place again, the withdrawal, the meek, passive, unresponsive silence he had seen when he had visited her with her brother.

With time and love and understanding, he felt there was a good chance of slowly merging the ’Cisca of now with the Francisca who once had been. And then, little by little, the housemaid would disappear, along with the shop-girl mannerisms, the saucy walk, the shallow pleasures.

But will she then settle for a Raoul Kelly, he thought. It would be a bitter irony to discover that her acceptance of him as a “boyfran” would be outgrown, along with her delight in soap opera, her collection of movie magazines, her taste for bright, tight clothing and semi-theatrical makeup.

As the afternoon did not seem to be going well, he decided to take the risk he had weighed and wondered about. He went up to the big parking lot and came back with the folder from his files. It contained a selection of the articles he had done in Spanish-language newspapers, cut to size and Xeroxed on the newspaper machine on 8½-inch by 14-inch sheets, and fastened into a clasp binder. He had made the selection with great care, leaving out those things which might trigger too many memories for her.

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)