She ran out and banged the door shut.

“Mom?” he said, but too quietly to be heard. He was propped up on his elbow. He lowered himself back to the pillow. She had slammed the door so hard it had jingled the row of little trophy cups on the high shelf over the doorway.

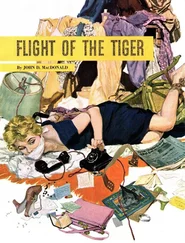

It was night. The light on the desk reached far enough to show indistinctly a slow movement of the three scale-model aircraft suspended from nylon filaments, hanging from the ceiling over his tall chest of drawers. Spitfire. Hurricane. B-29. Atop the chest of drawers in a narrow chromed frame was the picture of Betty. He could not see it, but he knew exactly how it looked. I looked right into the lens, darling, and pretended I was looking right at you. Happy birthday, darling. Happy, happy birthday .

This was his room, he thought. He won those trophies. He made those models. He slept in this bed. That was his girl. It was a strange kind of sadness.

There was no way they could understand. Not any of them. How could they be made to see how special and how terrible it was, last night when Crissy had clung to him, weeping hopelessly, like a little kid afraid of the dark. She did not have anyone else. Their time was growing short. She kept saying there was nothing they could do. Nothing. But the idea of Staniker having her again was unendurable. She had made those funny little hints. And she had said, “Don’t you see? This was all we were meant to have. But it’s so much more than most people in their whole lives, my dearest. There’s one clean way to finish it. If we have the strength.”

And then later, all too casual, turning away when he tried to look into her eyes, she had said, “There’s some horrid, big, brown rats living in the tops of my palm trees, dear. They’re getting terribly bold. Do you have a gun you could bring over? You could shoot them for me, maybe?”

It wasn’t much of a gun. He had checked to make sure it was still in the back of his closet. His father had given it to him one Christmas, when he was fifteen. It was a single-shot 22 rifle chambered for longs. Montgomery Ward. It threw high to the right. The half box of shells was in the back of the bottom bureau drawer.

The best way, he thought, would be to take the bolt out and wear those khakis which were roomier in the leg, and put it down his pant leg, muzzle down. In a little while. It was their bowling night. If they went, he could carry it out to the car without any pantleg nonsense. They might not go. Just to show him how upset they were. See what you’ve done to us? You’re spoiling everything for us, Sonny. After we’ve devoted our lives to you, boy.

He yawned and stretched. When he was away from her it was like being half alive. Everything was in monotone, like an old movie. Thoughts moved slowly, and his bones felt old.

Once again he let himself float back into sensual reverie, the images of the flesh, halted when his mother had knocked at his door. He knew that he could never have guessed how difficult it could be. Sometimes he would feel powerful as a giant, and, gathered into his great hands and sinewed arms, she would feel so sweet and little and whimperingly fragile, he would take her with a measured care, such a cautious awe and tenderness it seemed to make his heart melt and flow. And other times, in the tumbly striving gloom, she would seem to grow to an overwhelming weight, a huge warm bulging of thighs big as trees, belly like a meadow, furnace-door mouth, breasts like dunes, and the strong pulling of her arms would dwindle him to a little stick-figure of a man, drowned in the softness, held in purring, chuckling hunger, ticked close, and at last made to go into the scary puppety leapings that was not like pleasure but like all the world pulled down to a whine of bright lights, a shrillness of a single vivid and indescribable color, a grating and drawing and diminishing that was like the sense of falling which comes at the end of dreams.

When Sam Boylston walked into Staniker’s hospital room on Sunday afternoon at one thirty, the Captain was sitting in the arm chair in a cotton robe. Theyma Chappie was fixing a bowl of tropical blooms on the deep windowsill, pinching off the dead blossoms and dry leaves. She gave Sam a swift sidelong glance.

“I shall be down at the floor-nurse station, Captain,” she said. “Ring if you need me, please.”

As she was leaving, Sam went to Staniker, started to put his right hand out, changed to his left hand. As Staniker took it, Sam said, “I appreciate your giving me some time, Captain.”

“Sit down, Mr. Boylston. Sit down. I know how you must feel. Miss Leila was a fine little lady. It was a terrible thing to happen. You just never know. One minute everything is fine and the next minute — You just never know.”

Sam sat on the straight chair by the bed, readjusting his mental image of Staniker to fit the reality. The man was both bigger and better looking than he had expected. And there was a certain flavor of earnestness about him, of staunchness, one might easily find attractive. Yet there was something about him which reminded Sam of someone he did not like. It took him but a few seconds to pin it down. Big Tom Dorra, who along with old Judge Billy Alwerd had invested half the cash in Bix’s venture. Staniker did not have the hugeness of Big Tom, but the impact seemed strangely the same. There was the same flavor of a lazy gentleness which underscored rather than diluted an almost tangible maleness. The Captain and Tom Dorra both projected effortlessly that same promise of brute masculinity which had given some extraordinarily wooden actors long long careers in motion pictures. And just like Big Tom, in spite of the weather wrinkles and the smile wrinkles, the eyes themselves, pale, with coarse lashes, had the empty, bored distant malevolence of the bull elephant, the ruthless look and pattern of the stud.

He noticed an odd thing about the hair at Staniker’s temples. It was gray at the roots, gray for the first half inch, the dividing line between new color and old almost mathematically precise.

“Was my sister having a good time on the cruise, Captain?”

“That was a fine comfortable vessel, Mr. Boylston, and Mr. and Mrs. Kayd had me take them to interesting places. It would be a nice experience for anyone who didn’t know the Islands.”

“Did she seem to be having a good time?”

Staniker scowled in heavy thought. “I guess you’d want to know just how it was. She’d get moony about her boyfriend back in Texas. But that wasn’t all the time. There’s another thing, and I’ve run pleasure boats enough years to see it happen over and over. You put people on a boat and what it does, Mr. Boylston, it makes any little differences a lot bigger, especially if it’s family. Stella was a meek little thing, and that Mrs. Kayd, her step-mother, seemed bound on making that cruise pure hell for that little girl. Nasty nice. You know?”

“I know.”

“And Mr. Kayd kept criticizing his own boy every chance he got. Not a bad kid, that Roger, but his old man didn’t give him much of a chance. I guess Mister Bix kept getting the uglies on account of his wife was forever whining and complaining at him. When things got rough, Miss Leila would sidestep pretty good. She and my wife and me, we had to stay out of the line of fire. They’d keep trying to get outsiders to take sides in family trouble. I don’t mind telling you, Mr. Boylston, off the record, that Carolyn Kayd was real trouble. I think she liked things all messed up. Hell of a good-looking piece of woman, and she started giving me the eye after we’d been cruising a week or so. Just to needle Mister Bix. Even if my Mary Jane hadn’t been along, I’ve been around too long to walk into any kind of a setup like that. Maybe I’m making it sound worse than it was. Your sister had some good times. She hung one bull dolphin that like to give her fits. He spent more time in the air than he did in the water, but she got him up to the gaff, and when I yanked him aboard and he started going through all those colors as he died, she said she was sorry she hadn’t lost him. Nice little girl. A nice happy little girl. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away, as the good book says, but it doesn’t seem to be worked out too fair sometimes.”

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)