“I had some lavender-flavored rubbing alcohol, and I sopped a little hand towel with it and swabbed his face off, keeping it away from his eyes. His breathing slowed down. Then he opened his eyes and he was himself and he knew who I was. I asked him who I was. I said he’d called me Christy.”

“What was his reaction to that, Mrs. Hilger?”

“I guess it scared him to know he’d been out of his head. It would scare anybod—”

“No. I mean exactly what did he do and say?”

“At first he didn’t say anything. He closed his eyes. He pushed my hand away from his face. Not roughly. Just slowly and gently. Then he asked what he’d said. I said he was trying to make Christy understand something and he was asking her for help. I said that people in delirium don’t make sense. I said he was just a little wilder this time.”

“And there was a special reaction then?”

“I don’t know what you mean by special, Mr. Boylston. He seemed surprised. ‘This time?’ is what he said, lifting his head off the pillow. I told him that the other times he was just moaning and thrashing and mumbling.”

“How soon after that did he go into convulsions?”

“It wasn’t long after that. Four minutes. Five. It scared me half to death. I thought he was dying. I know what I should have done, but I didn’t know it then. You’re supposed to wedge something across their teeth, as far back as you can get it, so they won’t chew their tongue to ribbons. I ran and yelled to Bill and he came hurrying down. By then Captain Staniker was quiet again. Asleep or unconscious. He was like that without any change when they took him off and put him in the ambulance.”

He put the tape on fast wind, all the voices sounding like a nest of agitated mice, and, with a couple of pushes on the rewind button, located the resonant and antagonistic baritone of Bert Hilger, plumbing contractor and owner of the Chris-Craft named Docksie. He numbered himself among the boat-people. Sam Boylston was an outsider. A batch of boat-people had been lost at sea, and he resented technical questions from someone who did not know the bilge from the binnacle, yet was compelled to answer because of the familiar gratification of imparting expertise.

“Check and check and check again,” he said. “You stay healthy if you don’t depend on the gadgets, Boylston. You mistrust them every minute. Duplicate everything and check the gadgets against each other. I run on gas, so I got two sniffers in the bilge, independent of each other. But before I make a run I still crawl down there and hold a cup with a few drops of gas in it next to the probes to make sure the buzzers and blinkers work on both of them. I’m wired for separate electric on both engines, independent fuel supply, and I watch fuel consumption, battery levels, rate of charge like an eagle. I check the compasses against each other and against the charts. I got two big hooks rigged so I can drop them fast if I get into trouble. I listen to every piece of weather I can find on the dial. I carry spare wheels and a wheel puller. Hell, things have gone wrong. Things always go wrong. But if you don’t trust anything, you don’t get into bad trouble. When the sea is building, you’ll find the Docksie in a protected anchorage with all the water and supplies we need to wait it out.”

“Then you think the Muñeca should have had a detection device for gas fumes.”

“The question doesn’t mean anything. She was diesel. If I was diesel and had a gasoline generator and gas cans of fuel for it below decks, I would have had a sniffer. Some perfectly sound boat owners I know wouldn’t have. Most of them, maybe. It’s how careful you want to be.”

“Suppose Staniker was at anchor and wanted to turn on the generator.”

“Then without even thinking about it he would have opened some hatches and run the blower first. He wasn’t some Kansas clown on his first cruise, you know. He was running, and when you’re running you don’t think of any accumulation of fumes in the bilge, not with a diesel, because you’ve got air movement through the bilge. You pick it up with a bow ventilator arrangement and it runs through and comes out somewhere near your transom. But the way I see it, he ran into a freak situation. He had a following wind and sea at about the same knots he was making. So he was running with dead air below. It wasn’t moving.”

“And the explosion that blew him into the water could have ignited his diesel fuel?”

“I wouldn’t know about that. As I understand it, compression creates heat, and I’ve seen some of those custom jobs they make for heavy duty work up there in North Carolina. They’re solid. Any fuel has a flash point. Put enough heat on it all of a sudden, and it will go. And if it did, the only place anybody would have a chance would be if they were on the fly bridge. And even then you’d get seared pretty good, the way he did.”

“Does it seem odd to you that no other boat saw the fire?”

“Why should it? Let me show you on the chart here. He was north of Andros according to the approximate position he gave me, up beyond North Goulding Cays far enough so no one would see him from Morgan’s Bluff, Nicholl’s Town or Mastic Point. He was moving in toward coral head areas, and it was night, and nobody who didn’t know how to sneak through there, as he did, would be well clear of it, way out in this area, far enough away so they’d see a glow, but if they did, the normal guess would be some kind of fire on shore.”

“Mr. Hilger, could you show me a few other places on this chart where it would be the same sort of situation, I mean where a fire at sea would attract so little attention?”

“Well — let me see now. Mmmm. No. I guess you could say that was another part of the way his luck was running. When your luck goes bad on the water it seems to go bad in every possible way.”

“And it would be deep water there they tell me.”

“It’s the Tongue of the Ocean, Boylston, and it comes in pretty close to the eastern shore of Andros. It’s a steep one. Within a hundred yards, say you’re heading east, you can go from forty feet of water to six thousand. That’s why they’ve got that experimental base at Fresh Creek on anti-submarine warfare. That’s down the coast of Andros, about forty miles south-southeast of the Joulters.”

“Thank you ver—”

He thumbed the button that took it off playback, then pressed the rewind button. He put the reel back into the original box and put it into the drawer in the bedside stand. He loaded a new reel on the recorder, and put the little machine into the side pocket of his jacket as he left.

It was almost five thirty when Theyma Chappie admitted Sam to the tidy little apartment in the Harbour Heights development. She had been home from the hospital long enough to shower and change. Her dark hair was undone, ribbon-tied, spilling down her slender back. The ends of it were damp, and she smelled of flower perfume and soap. She wore a sleeveless rose-pink knit shift in a coarse soft weave, gathered at the waist with a narrow belt of the same material, flat white sandals with gold thongs. Her mouth was made up a little more abundantly than in the morning. She had a warmer, livelier look.

He accepted her offer of a drink and said he would take whatever she was having. It was gin and fresh fruit juices in large weighty old-fashioned glasses with a sprig of fresh mint. He sat on a severe couch upholstered in pale gray fabric. Under the glass top of the coffee table in front of him was a display of exotic seashells. She sat on a low footstool on the other side of the table, arms wrapped around her knees, and in reply to his question, she gestured with a tilt of her head toward the recorder, the one she had taken to the hospital and brought back. “Oh, it was a most easy thing. But I was frightened all the time it was there. You can see. Most of the tape is used up. He was much better today. Except for the speaking. His tongue is swollen and bruised. It is painful for him to talk or eat. He must speak carefully. But they did question him today. Dr. McGregory permitted it. The fever is gone. Sub-normal, actually. Pulse slow and strong. No rales in the chest. But these things can turn bad quickly.”

Читать дальше

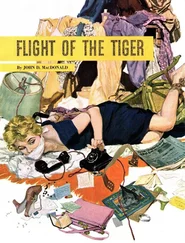

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)