This immaculate little old man was going to quietly dismantle all the works and dreams of Squires and friends, burn the rubble and sow their lands with salt. And some phases of this program would enrich Sir Willis in one way or another. In a sudden, expanded comprehension of self, Sam Boylston realized he had made exactly this same decision himself, had made it about big Tom Dorra and old Judge Billy Alwerd. Though their role had been peripheral, their actions had been illegal enough to give Sam his rationalization. There had been an icy little focus of satisfaction and anticipation in the back of his mind whenever he had thought of them since finding out about the money loaned to Bix Kayd. When he had time to devote to them, he would find out their every area of income and investment, and see to it that small things began to go wrong. A man in a boat who has to devote all his time to caulking the seams, bailing, working the pump, has no time for careful navigation, no time to look for the reefs. If Dorra and Alwerd were to respond with total speed and energy and calm intelligence to every challenge, he could do them no real harm. But those two were hunch players, drifting at half efficiency through a haze of myth, superstition and self-approval. Shrewder than most, perhaps, but capable of fatal mistakes in judgment if too many things started to go wrong at the same time. And, when they began foundering, he could reach into the chaos and pluck out a few useful things at sacrifice prices.

As his intent became more apparent to himself, Sam saw the similarity between himself and this scrubbed old man with the eyes as cold as Burmese sapphire. And he felt a curious contempt for Sir Willis and for himself.

As Sam left, amid the expressions of mutual gratitude, Sir Willis said, “Perhaps one day we might talk about the special advantages of setting up business interests here in the Bahamas. I suspect, dear boy, we might find some unexpected mutual benefits — of the sort you chaps from your province of Texas seem able to appreciate.”

“I’ll look forward to it,” Sam said, but knew from a flicker in cool blue depths he had not quite carried it off. The original feeling of affinity had faded away.

He telephoned Sir Willis at the bank on Friday morning at ten. Sir Willis said, “Bear with me, Boylston, if I seem a bit — indirect. Our friend was expecting a radio message from your fellow countryman Saturday morning. It did not come. Saturday afternoon he went to his vacation spot from his home base by float plane, and was left off there, along with a young chap who is in the way of being a personal aide and secret’ry. On Sunday evening our friend used his marine radio there at his place to ask the float plane to come by Monday morning and take him off. He went back to his home base, leaving the secret’ry chap alone there, should anyone come visiting, I expect. By now he has returned also, but I do not know precisely when. As to the friends of our friend, I had a chat with the one I thought most likely last evening. It became rather an ugly conversation, but it was all confirmed. There were two of them, as I suspected, beside our friend. I can guarantee silence on the part of the one I talked with. Much better if our friend has no inkling that I know of the nasty bit of work he hoped to arrange. Is all this sufficient for you?”

“I’m grateful to you, Sir Willis.”

“May I offer my hope that things will turn out far better than — you have reason to expect at the moment. Do let me know if I can be of any help. Matters which you might find difficult I could probably arrange quite easily. We are quite a small community, actually. And it would have been a great pity had anyone of your countryman’s special — talents acquired such substantial land interests here, particularly in such a manner. It would have been troublesome to oust him, as we most certainly would have, sooner or later.”

Sam Boylston’s room phone rang at ten o’clock Friday evening as he was pacing restlessly, uncertain as to what he should do next.

If it had been — as he was quite certain Sir Willis would term it — foul play, it had to depend on word of the money leaking out. The leak could have come from careless talk in Texas, in Nassau, in Freeport, possibly even in Miami. With a promise of a share of that much money, some very savage talent could be recruited along the lower coast of Florida. Small cruisers came over at will, and several men masquerading as sports fishermen could monitor the calls from the Muñeca and trace her and intercept her at the proper time and place.

But the timing of it seemed almost too close. The Muñeca had left Nassau Friday morning. Kayd had planned to meet Squires on Saturday. But he had not made his routine radio contact on Saturday morning.

Kayd’s shrewdness had to be taken into account. He would make certain that information about the fortune aboard didn’t leak out. He would certainly keep it from his family. And he would not take aboard any hired captain who had not been checked out very carefully.

What if the Muñeca had arrived at Musket Cay earlier, say by Friday evening? They were headed that way. The cruiser could make it comfortably. Just because Squires had arrived Saturday afternoon, it did not mean he had not arranged for a little reception party to arrive there, possibly by private boat, a day or more earlier. Or perhaps somebody in Squires’s confidence had arranged it without Squires’s knowledge. It seemed to fit the timing. Perhaps the logical course was to go to Freeport first, then back to Musket Cay.

His mind would travel in logical patterns and rhythms, but at intervals he could not anticipate, he would suddenly realize that every conjecture was based on the assumption all aboard had been slain and the bodies stowed aboard to sink with the boats into the great black depths of the Tongue of the Ocean. Logically it was an acceptable assumption. Emotionally he could not believe such a thing could have happened to Leila. She was too vibrant, too spirited, too totally alive to be wasted so mercilessly, so prematurely. In those moments remorse and grief and rage combined into an emotion as strong as a physical illness, darkening his vision, clogging his throat, giving him ripples of nausea which made cold sweat on his body and made his legs feel too weak to support him.

He was recovering from one of those moments when the phone rang and he heard Jonathan’s excited and unsteady voice say, “Sam? Are you there, Sam? They’re bringing Staniker in.”

“In where? Who is?”

“Some people on a boat. They found him somewhere, on some island, and they’ve asked for an ambulance to meet them.”

He reached the Prince George Wharf area in time. He found Jonathan in the crowd. A cruiser was angling in, spotlight trained on the dock area. A man was trotting, waving them along to a place inside the main wharves where the dock levels were suitable for small boats. The big cruise ships with their festival lights dwarfed the Chris-Craft. The ambulance was waiting. The cruiser edged in. Lines were heaved to the men on the dock. As the cruiser was moored, there was a silent lightning of flash bulbs and strobe lights, and the doctor and the ambulance attendants stepped aboard, carrying the stretcher.

By first light on Sunday, in the sea mist, on the incoming tide, Corpo was wading the flats east of his island, hunting scallops, humming tunelessly, speaking greetings to each one as he shoved it into the gunnysack fastened to his belt. He had guessed it would be time for them to be in, and knew he had to get out there before the tide deepened it too much.

And it pleased him to have the silence and privacy of the mist and the dead calm. They couldn’t see him from the mainland shore, from all their candy-colored houses. No doll-wives shading their empty little eyes to stare out at old Corpo as if he was a bug who’d moved too close.

Читать дальше

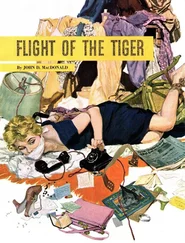

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)

![Джон Макдональд - The Hunted [Short Story]](/books/433679/dzhon-makdonald-the-hunted-short-story-thumb.webp)