‘And you think Willi Beckmann — the man in the morgue — might be the same man.’

‘I don’t think Willi Beckmann was dumb enough to chop her up and bury a severed hand that had his name on it. But it’s possible he could have told us something more about her. If he hadn’t been shot. Maybe enough to find her killer — the man the newspapers had dubbed the Grünewald Pork Butcher.’ I’d already decided to visit Willi’s apartment in Tegel, to see what evidence I could find before I went looking for Hugo. ‘Who knows? Maybe he still can.’

Brigitte listened in silence and then said: ‘My God, the things that must be inside your head. You go looking at things that no one should ever have to see, with no idea of the effect it’s going to have on your mind, and all for not much money. I don’t think you even know why you do it. Do you?’

‘Sure I know. Because I have nothing to say as a painter. Because I couldn’t finish my unfinished symphony. Because being a cop is a job for honest men, and since there are not many of those around these days, they’ll take anyone they can get.’

‘Well, I think you’re crazy. And if you’re not, then you soon will be. Still, I suppose that’s what being a detective is all about.’

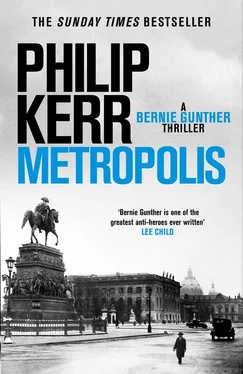

Willi Beckmann had lived in Tegel, part of the northwestern borough of Reinickendorf and not far from the giant Borsig locomotive works. The whole area was dominated by a modern red-brick ziggurat that was the model for the New Tower of Babel in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis . That had been a silent film — with talking pictures now arriving on the scene, it already looked like a remnant from the past. As for the Borsig works, there was nothing futuristic about it; noisy and dirty, it seemed a throwback to an industrial Berlin that was fast disappearing. Willi’s apartment was on the top floor of a more traditional Berlin building with its mustard-yellow walls, red-tiled mansard roof and a curving balcony that was home to a spectacular window box full of pink carnations, which possibly explained the buttonhole poor Willi had been wearing at the time of his death. The concierge admitted me to the apartment. He was a man of few words and those he had expressed a kind of awed pride in the size and layout of the accommodation.

‘I’d forgotten what a nice big apartment this is,’ he said. ‘All these rooms. And the ceilings so high. You could play tennis in here.’

He had very little curiosity about what I was doing there or indeed about Beckmann’s death. To my relief, he quickly left me alone.

There wasn’t a lot of furniture but what there was was good stuff — Biedermeier copies, mostly, and on the walls were prints of hunting scenes in the gardens of Schloss Tegel. Of course, the police had already been there searching for leads to the identity of the dead man’s murderer and, according to an official notice taped to the apartment door, they had taken away some photographs and papers.

Not knowing what they were looking for, they’d removed very little.

I had better luck. In a cylinder cabinet, I found a couple of photograph albums, and in these were pictures of a quartet of good friends. Several had been taken at a nearby restaurant on the edge of Lake Tegel. The quartet was made up of Willi Beckmann, Hugo Gediehn, Helga ‘Mustermann’ — I still didn’t know her surname — and Frieda Ahrendt. What was clear from the photographs was that Hugo and Frieda had once been lovers. Some time after the photos were taken Frieda and Willi became lovers, which was when they each had the tattoos made. None of the pictures provided a neat explanation for Frieda’s murder, but they were all the excuse I needed to detain both Hugo and Helga. These four wouldn’t have been the first good companions to fall out violently. There’s nothing like an old friendship to provide a solid basis for a lasting enmity.

Since I had the free run of the apartment, I spent another hour raking through drawers and closets, which is how I found several letters addressed to Frieda from her loving sister, Leni in Hamburg. I wondered if Leni even knew her sister was dead. I was still short of an ironclad motive as to why two of the people in the pictures had been murdered, but everything else seemed to be falling into place.

Leni’s letter had included a telephone number and since there was still a working telephone in Willi’s apartment, I called her.

‘Forgive me for telephoning you out of the blue like this,’ I said, ‘but my name is Bernhard Gunther and I’m a detective with Berlin Kripo.’ Choosing my words carefully, I added, ‘I’ve been investigating your sister’s disappearance.’

Leni sighed. ‘It’s all right, Herr Gunther. I know she’s dead. If she were alive she’d have contacted me. But it’s been almost a year. And I gave up all hope of ever seeing her again several months ago. We were very close, you see, always in touch. Also, the man she was living with in Berlin at the time of her disappearance, Willi Beckmann, he came to see me here in Hamburg and told me he thought she was dead, too.’

‘But why didn’t you contact the police?’

‘Willi said that for his sake and for mine we’d best not say anything about it to the police because the man who told him she was dead was a member of a criminal ring and very dangerous.’

‘Did he say what that man’s name was?’

‘He did. But I’m not going to repeat it now, even after all this time.’

‘Willi Beckmann’s dead. Did you know that?’

‘No.’

‘The man who murdered him is called Hugo Gediehn. And I’m going to arrest him today or tomorrow. Is that the name Willi told you?’

‘Yes, it is.’

‘I have him cold for Willi’s murder.’

‘May I ask how you know that?’

‘Because I have a witness.’

‘A witness who’ll stand up in court?’

‘Yes.’

‘Sure about that?’

‘Yes. I’m the witness. I saw him pull the trigger on Willi. But he’s also my only suspect in your sister’s murder. Frankly, I was hoping you might be able to help me out there.’ I paused, and hearing nothing, added, ‘You’ll be quite safe, I can assure you. No one need ever know I spoke to you.’

‘How can I help?’

‘I have a suspicion as to why Hugo killed your sister, but I have no real proof. Getting proof would be help enough, I think.’

‘The why is quite simple. Hugo and Frieda were lovers. Then Willi enticed her away from Hugo — Willi was a very attractive man — and Hugo decided to get his revenge. Killed her. Buried her in a shallow grave somewhere. That much he told Willi. To torture him. Of course, Hugo knew that Willi was also in a ring, and that the last thing he could ever do was talk to the police. But I don’t understand, Herr Gunther. Why did Hugo kill Willi now, after all this time?’

‘I can’t be sure, but I think it was because Willi went and stole Hugo’s new girl, Helga.’

‘Makes sense, I suppose. If you’re looking for him, Hugo has an apartment in Kreuzberg. But I expect you know that.’

‘Yes. I do.’

‘Will you let me know what happens?’

‘Of course.’

‘Thanks. And good luck. Hugo being Hugo, you might need it.’

Back at the Alex I made out a good case for Hugo Gediehn’s arrest to Weiss and Gennat and, accompanied by several heavily armed uniformed officers, we proceeded to his apartment in Kreuzberg and took him into custody. To my surprise, he came with us quietly, saying very little except to insist we had the wrong man, a detail to which we might have paid more attention if it hadn’t been for the Bergmann MP-18 that was still in his car and my discovery in his desk drawer of a single souvenir photograph of Frieda’s severed hand, the one featuring the tattoo of Willi’s name. It was what the lawyers called prima facie evidence, which is just a fancy way of saying that as soon as Gediehn saw that we had the photograph, his expression changed and all the colour drained from his face as if we’d introduced him to a pack of hungry wolves.

Читать дальше