There was, of course, a sound forensic reason for this exhibition; it was argued that information about a deceased person was often very hard to obtain from a metropolitan citizenry that was enormously diverse except for a shared dislike of Prussians and the Berlin police, and the display of corpses, while no doubt titillating, sometimes produced valuable information. None of this counted for much with me. You just had to eavesdrop on what was said to know that the people who went to see the stiffs and be horrified were the same ones who would have bought a sausage and gone to watch a man broken on the wheel. Sometimes there is nothing quite so dreadful as your fellow man, dead or alive.

None of the bodies already exhibited in the central hall were familiar to me, but I wasn’t in search of a name or evidence so much as to confirm something I’d heard Arthur Nebe talking about in his speech to the Prussian Police Officers’ Association: that the Hanno showhouse was very popular with Berlin’s artists in search of something to draw. I assumed, wrongly as it transpired, that these artists were merely following in the tradition of Leonardo da Vinci and perhaps Goya, looking for human subjects that wouldn’t or couldn’t move while you were drawing them.

As it happened I only saw one artist at the Hanno showhouse that Tuesday afternoon. To my surprise, he wasn’t drawing anatomical studies but actual wounds — throats that were cut or torsos that had been comprehensively disembowelled — and he seemed not at all interested in drawing dead men, only dead women, preferably in a state of undress. He was about forty, thickset with dark hair and, for some obscure reason, dressed as an American cowboy. A pipe was in his mouth and he was almost oblivious of everyone around him — everyone who was alive, that is. Several times I looked over his shoulder at his sketchbook just to check my own appraisal of his work before I eventually introduced myself with the Kripo warrant disc. I’m no art critic but the word I’d have used to sum up his style was depraved . I suppose if he’d been dressed like an Apache Indian I might even have arrested him.

‘Can we talk?’

‘S’up? Am I in trouble?’ he asked, and almost immediately I knew he was a Berliner. ‘Because I’m quite sure there’s no law against what I’m doing. Nor any rule in here that I’m breaking. I already asked the people in charge of this place and they said I was free to draw anything I liked but not to take photographs.’

Despite his eccentric appearance — he was even wearing spurs — the Fritz was a Berliner all right: asserting your rights in the face of Prussian officialdom was as typical as the accent.

‘Well, then, you know more than I do, Herr—’

‘Grosz. George Ehrenfried Grosz.’

‘No, you’re not in any trouble, sir. At least none that I know of. I’d just like to talk to you, if I may.’

‘All right. But what shall we talk about?’

‘This, of course. What you’re drawing. Your preferred subject. Murder. In particular, murdered women. Look, there’s a bar nearby, on Luisenstrasse — Lauer’s.’

‘I know the place.’

‘Let me buy you a drink.’

‘Is this official? Perhaps I should invite my lawyer.’

‘What’s the matter? Don’t you like our fine capital’s police?’

He laughed. ‘Clearly, you haven’t heard of me, Sergeant Gunther. The law and my work don’t seem to get on very well right now. And not for the first time, either. Currently I’m being prosecuted for blasphemy.’

‘Not my department, I’m afraid. The only picture on my wall at home is a mezzotint of Hegel and you would think it had been originally drawn by his bitterest enemy. If he had his throat cut and his arse hanging out of his trousers he couldn’t look any worse.’

‘History teaches us that no one ever learned anything from Hegel. Least of all about art or even history. But yours is a compelling image. I shall borrow it.’

In Lauer’s I bought us each a beer — two foaming glasses of Schultheiss-Patzenhofer, which was the best beer in the city — and we sat down at a quiet table. Not that it mattered much to George Grosz; he didn’t seem to mind that people looked at him as if he were a lunatic; maybe that was supposed to be artistic in itself, like walking your pet lobster through the streets on a blue silk ribbon. While we talked and sipped our beers he was also drawing me with pen and ink, and doing it with great skill and speed.

‘So what’s with the Tom Mix outfit?’

‘Did you ask me here to talk about my clothes or about my art?’

‘Maybe both.’

‘You know, I might be tempted to dress up as a police officer if I could buy myself a uniform.’

‘You wouldn’t like the boots. Or the hat. Or for that matter the pay. And it probably is a crime to dress up as police in this town. On the whole, cops in Berlin don’t have much of a sense of humour about such things. Or about anything else, now I come to think about it.’

‘You would think they would, considering those boots and that leather hat. There is one thing that cannot be denied, however: the truncheon always seems to hit at the left. Never at the right.’

I smiled weakly. ‘Haven’t heard that one before.’

‘Witness Saturday’s demonstration in which a communist worker was shot.’

‘Are you a communist?’

‘Would it surprise you to learn that I’m not?’

‘Frankly, yes.’

‘I once met Lenin, that’s why I’m not a communist. He was a most unimpressive figure.’

‘So might I ask, why would a man who’s met Lenin dress up as a cowboy?’

‘You might call it a romantic enthusiasm. I guess I’ve always loved America more than I love Russia. When I was a boy I read a lot of James Fenimore Cooper and Karl May.’

‘Me too.’

‘I’d have been surprised if you told me any different.’

‘It’s said that as well as his fascination for the Old West, Karl May had a peculiar enthusiasm for using pseudonyms.’

‘True.’

‘So is George Grosz your real name? Or is it something else?’

Grosz fished in his jacket, took out his card and handed it to me silently. I glanced over the details, held the card up to the light — this wasn’t just for show, there were plenty of forgeries around — and handed it back.

‘But as it happens you’re right,’ he said. ‘I also enjoy using pseudonyms. Anything like that seems not only possible when you’re an artist, but excusable, too. Even necessary. The reason a man becomes an artist these days is to make his own rules.’

‘And here was me thinking a man only becomes an artist because he wants to paint and draw.’

‘Then I guess that’s why you became a policeman.’

‘What’s your favourite book by May?’

‘It’s a toss-up between Old Surehand and Winnetou the Red Gentleman .’

‘I assume you must have heard about the killer the Berlin newspapers have dubbed Winnetou.’

‘The one who scalps his victims? Yes. Ah, now I begin to understand your interest in me, sergeant. You think that because I sometimes draw murdered women I might actually have killed someone in real life. Like Caravaggio. Or Richard Dadd.’

‘It certainly crossed my mind.’

‘Tell me, did you see any active service?’

‘Four fun years in one place after another. But always the same nasty trench. You?’

‘Jesus, four years? I did six months and it damn near killed me. They had me training recruits and guarding prisoners of war, on account of how I was partly an invalid.’

‘You look all right now.’

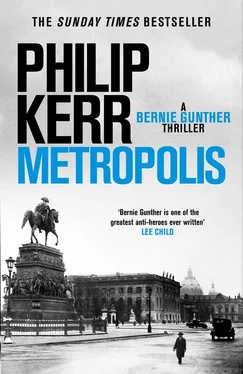

‘Yes, I know. I’m ashamed to tell you they kicked me out twice. First because of sinusitis, and the second time because I had a breakdown. They were going to execute me as a deserter, but then the war ended. But before it did I saw more than enough for it to affect my work. Perhaps now and forever more. So my themes as an artist are despair, disillusionment, hate, fear, corruption, hypocrisy and death. I draw drunkards, men puking their guts out, prostitutes, military men with blood on their hands, women pissing in your beer, suicides, men who are horribly crippled and women who’ve been murdered by men playing skat. But chiefly my subject is this: hell’s metropolis, Berlin itself. With all its wild excess and decadence, the city seems to me to constitute the very essence of true humanity.’

Читать дальше