And then come in again all of a sudden, and this time cut just a little bit deeper than before.

Now.

He picked up the phone and dialed Sheer’s number from memory. This was the first time he’d ever telephoned the old man, but he knew his number by heart. He knew the old man backward and forward.

The phone rang four times, and then the old man picked the receiver up and said “Hello?”

“Hello, Joe? Joe Shardin?”

“Speaking,” the old man said doubtfully, as though he thought he recognized the voice.

Not that Younger had meant to keep it a secret. He identified himself right away, saying, “This is Captain Younger, Joe. I’m sorry to disturb you this way, I really am. I wouldn’t do it for the world if it wasn’t absolutely necessary.”

“What is it this time, Captain?” The old man’s voice was cold as ice.

“This won’t take long, Joe, I’ve just got to check for our records. I believe we’ve got the wrong spelling of your name down here, and I figured the best thing was just to check with you. Now, what it says here, it says S-H-E-E-R-D-I-N. Now, that isn’t right, is it, Joe?”

There was silence on the line.

Younger said, “Joe? Are you there, Joe?”

“What do you want , Younger?”

“Is that the way you spell your name or isn’t it? Joe, there’s no need to get touchy about this, all I want—”

“You know how I spell my name!”

“Well, let me just make sure I’ve got it straight here, I wouldn’t want to—”

“You’d better cut this out, Younger. If you know what’s good for you—”

“Joe? Is that you? What the hell are you talking like that for, Joe?”

“You know what I’m talking about, you son of a bitch, I’m talk—”

“Joe, you never talked like that to my face. Is that the way you felt about me all along? And here I thought we were friends, Joe. We always talked together so easy, there was never any secrets between us, no hard feelings—”

“This is harassment, Younger, that’s what it is. You don’t think I know the law?” The old man was making an obvious attempt at self-control; his voice trembled with the need to shout, but did not shout. “I’ll get me a lawyer, you son of a bitch, I’ll have you—”

Younger said, pouring his voice into the telephone like maple syrup, “You want to make a formal complaint against me, Joe? You sure that’s what you want? You’d have to come down here to the station, if that’s what you wanted, Joe. It’s cold down here, you know that? Cold and hard, with bars on the windows, not nice and warm and soft and comfy like you got at home. You got old bones, Joe, old bones and old skin and old blood; you sure you want to come down to this place?”

“You can’t get away with this. I know my rights. This is harassment; you can’t get away with it.” But the trembling in the old man’s voice was more pronounced now, and from a different cause.

Younger said, “The way you get all excited, Joe, over nothing at all, somebody might think you had something to hide. That’s no way to carry on.”

“If you think you’ve got something on me, then why don’t you do something about it?”

Younger smiled into the phone, and let a few seconds go by before he answered, seconds for the old man to hear what he’d just said, hear the echo of his own words, hear what they sounded like. Then he said, “What do you suggest, Joe?” His tone purred, like a cat.

There was silence again, until finally the old man said, “Just leave me alone.”

“I’ll leave you alone, Joe. All you have to do is tell me how to spell your name, that’s all, tell me if I’ve got the right spelling here. That’s all I called for, Joe.”

“Sure.” The old man sounded exhausted.

“Now, here’s the spelling I got, Joe, I’ll give it to you again. You listen close, and if it’s—”

“I heard it the first time,” said the weary voice. “You know it’s wrong.”

“Well, that’s what I figured, but I wanted to be sure. Now, how’s the right spelling, Joe?”

“Do we have to go through this?”

“Just spell it out for me, Joe. Slow and clear, and I’ll write it down here.” Younger smiled and picked up his cigar from the ashtray and said, “I’ve got a pencil right here.”

The old man spelled out his alias, slowly, saying each letter as though he were too worn out to hold the phone, as though he’d fall over any minute. He spelled the false name, and when he was done Younger said, “There, now, that wasn’t so tough, was it? Why’d you carry on like that, Joe? You get up on the wrong side of the bed this morning?”

“Is that all?”

“For now, Joe.”

Younger hung up, and put the cigar between his teeth, and smiled to himself.

Younger pulled to a stop in front of the old man’s house. He rolled down the windows and turned the two-way radio up to full blast; nothing was coming from it right now but static. Then he got out a fresh cigar, unwrapped it, lit it, and settled down to wait.

After a minute the radio sounded off, a guttural voice, distorted so much by the extra volume that the words couldn’t be made out. Younger just sat there while the voice thundered away, and then the voice stopped and there was just the scratching static again.

He didn’t look towards the house. He didn’t have to. He knew the old man was in there, and he knew the old man could hear that radio, and he knew the old man would have to look out and see him sitting here. Younger didn’t have to watch the house to see a curtain rustle, see an old face appear in a window; he knew what would happen, without watching.

Still, nothing happened for a while. Every now and then the loud voice roared out words that couldn’t be understood. Between times the static crackled away, and Younger smoked his cigar down to a stub and threw the stub out the window into the street.

Half an hour went by. Younger didn’t move. Nothing happened.

Finally, the screen door on the old man’s porch slammed open, crashing around into the wall. Younger turned his head and saw the old man come storming out of the house. He came down the front stoop and along the walk, his knobbly old hands closed up into fists. He came over to the car and bent forward and looked in the window and said, “What are you doing here?”

“Hi, there, Joe. You over your mad?”

“Why are you parked in front of my house?” The old man was trembling all over, hands and head and voice. He looked as though any second he’d leap for Younger’s throat.

Younger spread his hands, being innocent. “I’m just taking it easy, Joe,” he said. “Out on patrol a while, and then pull to the curb and rest a few minutes.”

“You’ve been out here half an hour!”

“Joe, about that phone call the other day. I’ve been thinking it over, and if I said anything to offend you, I want you to know I’m sorry.”

“You can’t keep this up forever, Younger.”

“Joe, all I want in this world is for us to be friends. I told you all about my Army experiences because I want you to know about me, just like I want to know about you. Friends, Joe, that’s all. Share our experiences.”

The old man closed his eyes. He was bent forward, his forearms on the car door, his head framed by the open window. With his eyes closed that way, he almost looked dead; lines of age mingled with lines of weariness and worry in his face, making it look like an overdone pencil sketch.

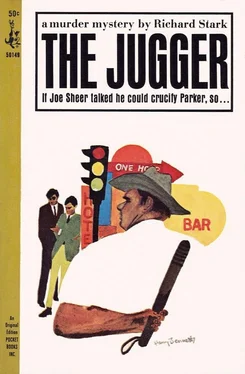

“Abner Younger and Joe Sheer,” Younger said thoughtfully. “It sounds like one of those old-time vaudeville acts, doesn’t it? You ever do any vaudeville, Joe?”

The old man’s eyes were open again, staring at Younger. “What did you say?”

Читать дальше