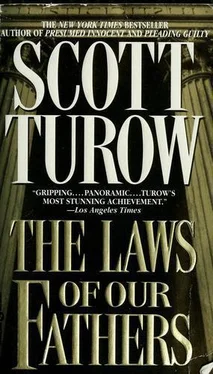

Scott Turow - The Laws of our Fathers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Scott Turow - The Laws of our Fathers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Laws of our Fathers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Laws of our Fathers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Laws of our Fathers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Laws of our Fathers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Laws of our Fathers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'It's like I said a while ago: he'd pay in the end and I'd be no better off than I was to start. It's not really workable.'

'Oh, there's always a way. It's only details,' Eddgar added, as if particulars were not the stuff of life.

I was seated in the living-room armchair, picking at the threadbare patch where the ticking showed through.

'You don't honestly think I should do this, man, do you?'

'Seth, what I think you should do is join the armed struggle. But I'm not so foolish as to believe that's likely to occur right now.' He'd picked up Nile's stuffed animal and his blanket and he put them down now on the sofa, where the boy still slept, oblivious to our hushed conversation. 'May I tell you a story? This is the worst story I know. The worst. I hate even to think about it. But I have a point to make.'

He sat down on a milk crate we used as a coffee table and paused to hike each of his pants legs, his preparations deepening the mood.

'When I was fourteen years old,' Eddgar said, 'I went with my father to the Overlook Valley Hunt Club. What it is in the life of the South – what it is that when there are so many as six prosperous white families in a 50-square-mile region they will organize themselves in either a hunt club or a country club or some similar pastoral enterprise, what it is I have never fully explained to myself, but my father, like his father, was a member of this club, and on Saturday afternoons, as his week was at an end and he prepared himself for our Sabbath on Sunday, he would adjourn to this club and drink Tennessee whiskey until the sun had set and my father was drunk as a lord. I was terribly embarrassed to see my father in that condition – he took a high red color, bright as a geranium, and it was also an unscrupled breach of his own religious principles for which he never made one word of apology. I hated to go with him, but I was raised in the kind of family where you simply said, "Yes, Daddy," when something was required and so I went along on many a Saturday, becoming, I suppose, educated in a tradition which I'm sure he expected me to take up as my own, listenin to large men with the characteristic names – Bear and Dog Head and Billy Ray – drinking bourbon with mint and sugar water, telling about critters they had shot and women they had known. All right?' he asked.

With this story, Eddgar was at home – in every sense. His lexicon had changed and his accent deepened. He had told the tale many times, I knew, practiced it, but Eddgar held me as he always did. I nodded quickly for him to go on.

'Well, the tiny little town of Overlook was near the club and you had to drive directly through it to get back to my father's plantation. It was like most little Southern towns: white and colored patches separated by the railroad tracks; not so much as a streetlight yet because we hadn't gotten Rural Electrification. And one evening when my father had drunk himself silly, turned red as those dirt roads, just absolutely radiating the heat of drink, he came flyin round the corner and plowed smack into the front of some old shivering heap that was stopped politely at a sign there in the colored section. I must say this wreck shook up both my daddy and me. He bounced his head against the windshield and took a good lick there, and began spouting a skinny little stream of blood that ran down into his eyes, but finally we collected ourselves and looked out to see some poor Negro man climbing out the door of his car, a rural fellow in a checkered shirt and soiled overalls, who considered the mess that had been made of his Ford. Its entire front end was stove in, completely limp and useless, except for this little white-hot hiss of steam shooting out like some starving cousin of Old Faithful.

'Now by whatever principle of misfortune that was then operating in Overlook, there was not another witness on that street, not another soul besides this man and my daddy and me who'd seen my father come tearing round that corner, as if the devil himself were in pursuit. And my father got out of his car and he came up to this man – not someone I knew, just some poor terrified black fellow – and my father looked at him and he pointed to his head and he said, "Nigger, you see what you done? Now you got one minute to get some of those other boys out here and get this car of your'n outta my way, or I'm gonna be callin Bill Clayburgh and I'm gonna have him run you in."

'Well, I suppose I should have been used to that. I can't tell you how my father treated the sharecroppers. When I was a boy, there was one fellow who had accidentally killed a cow, and my father and Billy Clayburgh, the sheriff, and some other white men hog-tied that fellow and held him under the river until he admitted killing that cow and agreed to let the price of that cow be taken out of the pitiful sum that was called his wages. But this wasn't the plantation, this was town, where my father was, as a general matter, better behaved. But I guess his true colors, so to speak, were showing. And he looked that poor man up and down, up and down, that poor black man who stood there wondering, Can this really be happening, can this white man just shoot around a corner, drunk enough that you can smell it standing five foot away, and make a total wreck out of my car that I worked so hard for and give me not a penny's recompense? Can he do that, or is there some small particle of goodness in this world that will prevent that? And then he looked past my father and caught sight of me in the front seat. His eyes loitered on mine. It wasn't a plaintive look, cause this man knew better than that and he was surely too proud to beg. He just looked and kind of asked me in a way, You too? You gonna do this too? Is this here going on and on? I knew what he wanted and so did my daddy, and he just said, "Don't you look at him, he seen the same as I have." And I said not a word.

'Well, that fellow didn't have any choice then and soon enough the man did what my daddy told him. He went in and out of some of the little houses, with their tarpaper sides, and collected some of his kin, some friends from out of a store up on the next corner, and by and by they came out and pushed the car out of the way and we left there. And my father, he wasn't done, he rolled his window down and said, "Don't you niggers let this happen again neither."

'And I say this is the worst story I know, because I just watched. I was fourteen years old. But I knew right from wrong. I knew brute authority from justice. And I spoke not a word. Not because my heart didn't ache to do it. But because I lacked the courage.

I hadn't planned my escape well enough in my mind. I hadn't yet prepared the path to my own freedom. Oh, I wept my eyes out that night and the nights following. And my resolve grew. And I swore to myself that whatever happened, I would never tie my tongue out of fear of my father or anyone else who was doing what I knew to be plain wickedness. In the years since, I have often heard my father say he raised his worst enemy in his own home, and I take pleasure when I hear him saying that. Because however else I judge myself, I think at least I've kept my word.'

He looked up to be sure he had my attention. The voice of a neighbor's TV drifted through the apartment, a commercial for a fast-food chain that seemed boldly inappropriate.

'Now I don't know a thing about you and your father, Seth. But let me tell you this much: Free yourself. If you are going to do something as dramatic as running away from your country and allowing some grand jury to indict you and the FBI to hunt for you coast to coast – make sure that it's not for nothing and that you are free on your own terms. If you can't make my revolution, then make your own revolution. Make the revolution you can -and triumph at it. That's what I say.'

He lifted up his sleeping boy and barely brought his lips to Nile's brow, while his eyes remained on me, knowing that as ever he'd made a deep impression.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Laws of our Fathers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Laws of our Fathers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Laws of our Fathers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.