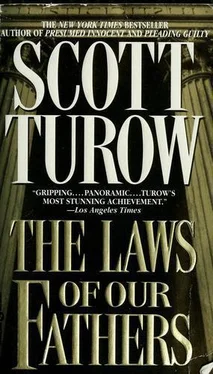

Scott Turow - The Laws of our Fathers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Scott Turow - The Laws of our Fathers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Laws of our Fathers

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Laws of our Fathers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Laws of our Fathers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Laws of our Fathers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Laws of our Fathers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Much of what I knew came from what I'd read – almost unconsciously – or what my mother eventually told me. I learned the few details I was allowed in my teens and largely in answer to my own ceaseless question to her: What was wrong with him, this man, my father? The stories I was told, in the barest strokes, were so alien to the secure envelope of University Park – its streets canopied by elderly elms, its confident persistent values and enduring social ethos of calm, intellectual debate – that I was truly years in absorbing them, some kind of titration of my own experience that took place in infinitesimal measure like medication being dripped by IV, tear by tear, into the blood. And even so they remain to me the very quintessence of horror: how my mother's husband had disappeared from her for good, as they were sorted by gender in one of Birkenau's lines. How my father's six-year-old boy was shot dead right before him at Buchenwald. The inhuman work. Meals of boiled grass. The unfathomable nature of what it means to have survived this utter blackness.

I rigidly avoided any conscious thought of my parents as the victims of any of those barbarities, and never took account of the mark their experience had made on me. Sonny had shipped literally hundreds of books from home. I had taken only four or five: The Diary of Anne Frank; The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Talcott Parsons; Alan Bullock's biography of Hitler. A few lonely volumes, they stood together on the lee end of one shelf amid the board-and-cinder-block bookcases erected along every free wall of our flat in Damon. Even seeing them side by side, I had absolutely no sense of what connected them. They were simply great books to me, consumed in college in hours of isolated reprieve from life's furies. I did not see any relationship between my parents' past and my political passions. I didn't recognize the futile deal I'd silently negotiated with myself: that if the world could be reformed, made right, if I knew there could never be another Holocaust, I would be free of the burdens they had placed upon me. It was all invisible to me. Instead, during those years, I had an unexplained phobia which filled me with so much racing panic that I was always forced to leave the room whenever I saw scenes in cowboy movies of cattle being branded.

In the aftermath of the melee at the ARC, demonstrators -consistently reported to be wearing the red arm sash of One Hundred Flowers members – had rampaged on campus. Windows in most of the buildings on the main quadrangle were smashed and glass vials of sheep's blood were splashed on the buff bricks. A smoke bomb was hurled through a basement window into Ryerson, the main undergraduate library. It was closed for four days and hundreds of thousands of volumes were removed to protect them from the lingering stench. Another bomb had been dropped down the chimney of the headquarters of the Damon Security Corps. According to reports, the bomber had slipped in his haste and cascaded off the tile roof, thudding to the ground, feet first, right outside the police station windows. The cops claimed he had been gathered up by other arm-banded rads, who carried him away, his foot, or ankle, or lower leg severely injured. Emergency rooms throughout the Bay Area had been combed, but the bomber was not identified.

On campus and on the Boul the talk for days afterwards focused on how it all went wrong. The campus police announced that Eddgar was under investigation for inciting to riot and claimed that his boisterous, singing quotation from The Little Red Book was the cue for the rocks to fly. But I spoke to dozens of people who had been at the head of the crowd and were certain the cops had struck first, clubbing a woman whose dog had innocently approached the police line. Pressed, most of these witnesses admitted they had merely seen her bloodied face. No one seemed to recall the batons falling on her. Some said she wore a One Hundred Flowers sash, and others were clear she hadn't. The woman could not be found. Eddgar calmly denied any role in the provocation.

'How foolish do you think I am, Seth?' he asked when I finally attempted to talk to him about it the following week. 'Do you really believe the faculty apparatchiks? The administration's theories -why, they're actually amusing. I'm not fooling. They paint me as the arch manipulator, the grand schemer with control over scores of lumpen rebels. And yet they want to claim I would stand in public and issue signals to a mob? Does that sound like a well-conceived attempt to subvert anyone but myself?'

I knew that this speech was rehearsed, that it had been given a dozen times already. Only last week, I had heard Eddgar quote Sun-tzu to June. 'War is deception,' he had said. Eddgar never explained – nor did I dare ask – how the smoke bomber, with his broken leg, arrived under our stairwell. But I wanted to believe him when he denied orchestrating violence.

Sonny was far more skeptical. We quarreled about Eddgar all the time.

'At least he's not like the head cases out on Campus Boul saying, "How can I make the world better for me?" ' I explained to her one night. 'He doesn't say, "Let's change everything, but make sure there's still plenty of LSD and lots of cool James Bond movies and someone to do my cleaning." What I think is that he's said to himself, "If I was poor, if I was dispossessed, if I was, you know, like Fanon says, one of the wretched of the earth, how would I react? If I had these smarts, what would I do? Would I put up with this crap for an instant?" And he's being honest when he says the answer is no. He'd want to smash everything that kept him from being equal and free.'

'And you agree with him?'

' "Agree?" No. Not completely. But I mean, I'm more with him than against him. "Whoever sides with the revolutionary people is a revolutionary." Right?' I smiled puckishly and Sonny made a face. 'Christ,' I said, 'why do I have to explain this to you. You're the one who was raised as a Commie.'

‘I wasn't "raised as a Commie." It's not like being a Baptist, baby. My mother belonged to the Party. Not me. And that doesn't make her the same kind of Stalinist zealot Eddgar is. He'd think she's a Trotskyist.'

Sonny always stuck up fiercely for her mother. During her term as president of her pipefitters' local, during World War II, Zora had appeared on the cover of Life – Wendy the Welder – with her acetylene torch glimmering like the Lamp of Liberty on the lowered visor of her mask. She was famous then. But because she was a Communist, and female, she was hounded from leadership and, eventually, from the union once the men came back. At the height of the McCarthy years, Zora had packed canned goods and blankets in two suitcases, expecting the army any day to take Sonny and her to the camps.

Sonny was cheerfully tolerant of her mother's eccentricities. Zora tended to call out of the blue and would keep Sonny on the phone forever. She would sit locked in the bedroom, even when we had guests in the apartment or people waiting elsewhere. By habit, Sonny never disagreed with her. She was silent. Zora talked.

'So what did she say?'

'Not much.'

'In an hour and a half?'

Sonny shook her head. It went beyond her power to explain. 'You know her.'

I didn't really. I had met Zora on only a few occasions. She was a tiny woman, not more than five feet, if that, always smoking Chesterfields. She had one walleye and heavy glasses and barely filled out her shirtwaist dress. I recall being impressed by the strings of muscles in her forearms. A tough bird, you'd say. The few times Sonny brought me by, Zora had not directed a single word to me, including hello. Instead, she soon launched into an account for Sonny's benefit of some recent outrage she had suffered – unemployment, landlord troubles, a union steward who had become a management whore. Small and quick, racing back and forth, Zora reminded me of a hamster in a cage. She screamed, spat words, raged her hands through the air, as she rambled at enormous speed and volume.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Laws of our Fathers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Laws of our Fathers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Laws of our Fathers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.