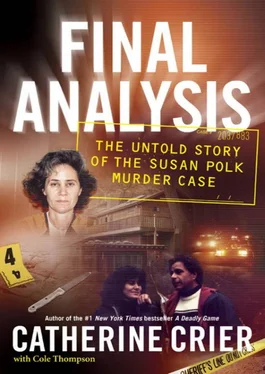

After eleven days of jury selection, the trial finally got underway that Tuesday with O’Connor’s blow-by-blow recounting of the night that Gabriel Polk discovered his father’s “motionless body” covered in blood and lying on the floor of the family’s guest cottage.

A commanding figure at well over six feet, O’Connor grabbed the courtroom’s attention when he stood to address the jurors. In his opening remarks, he told the panel of six women and six men that the Polks were in the middle of a “heated divorce” when Susan confronted Felix that October night. According to O’Connor, Susan was furious after learning that a judge had awarded Felix custody of their minor son and given him sole occupancy of the house while she was out of town. Even worse, Felix had managed to have her monthly support payments slashed from six thousand eight hundred dollars to one thousand seven hundred dollars.

It was enough to kill for, according to O’Connor. Felix’s injuries were “of a man fighting for his life,” he continued. “In contrast, the defendant had almost nothing. Clearly, it was a one-sided battle.”

The prosecutor pointed out that Felix had been stabbed numerous times; sustaining six incise wounds and defensive-type wounds on his hands, forearms, and the soles of his feet. Police observed redness around Susan’s eye and small cuts on her hand. It was most telling, though, that she publicly denied any involvement in her husband’s death for some time, although she claimed to have privately admitted her role to family members and her attorneys soon after her arrest in October 2002.

“Now she claims she killed him in self-defense,” O’Connor said, resting his gaze on the jurors. “The defendant is nothing but a cold, callous, calculating murderer. She got wind of what was happening in the divorce proceeding. She became angry… and came home [from Montana] to take care of business.”

Rising from his seat at the defense table, Dan Horowitz disputed the prosecutor’s allegations. “My client defended her life against an attack by a rage-filled, brutal, aggressive man who was also her husband,” Horowitz began in a soft voice.

Promising to dispel the prosecution’s claim that his client killed her husband for financial gain, he said, “This concept of the financial divorce is wildly unsupported.”

Susan wore a blank expression as her lawyer pointed out that she was the one who kept the family finances and was aware that once the court-appointed accountant reviewed the couple’s financial background it would become clear that the information Felix had provided to the court was inaccurate.

“Susan Polk was going to get her money back retroactively,” Horowitz insisted.

The defense attorney used his opening remarks as an opportunity to relate details of Susan’s childhood and to tell jurors of her early sessions with Felix Polk as a fifteen-year-old patient. He described the therapist as a delusional narcissist who “hyper-controlled” his wife and children and proclaimed that Susan and her family members would take the stand to testify as much.

At one point, he even drew a parallel between Felix Polk and fanatical cult leader James Warren “Jim” Jones, the American founder of the Peoples Temple Church in San Francisco and later Jonestown in Guyana. It was Jones who organized the mass suicide of 914 of his followers, including nearly three hundred children, and convinced them to collectively drink a Kool-Aid cocktail laced with poison in November 1978.

Horowitz insisted that just as Jones gained control over his disciples, Felix won psychological control over Susan by molesting her under hypnosis at the tender age of sixteen, and then continuing the abuse with threats and beatings over the course of their marriage.

From the front row of the gallery, Horowitz’s wife, Pamela Vitale, listened intently as her husband next introduced Felix’s little-known secret: that he had been committed to a psychiatric hospital after suffering a “schizophrenic reaction” in the mid-fifties while serving as a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy. It was news to many in the courtroom that Dr. Polk had spent nearly one year in a locked ward of a U.S. Naval Hospital. Horowitz promised more on Felix’s hospitalization through testimony from a defense expert who would explain how Felix’s mental condition made him prone to “outbursts of rage, violence, and anger.”

“Susan Polk defended her life against an attack by a vengeful, rageful, aggressive man,” Horowitz insisted. “She was on her back. She fought him off and lived.”

In spite of Horowitz’s strong opening, the trial did not get off to a good start. Jurors seemed skeptical of the defense’s claim that police had mishandled evidence. In addition, Horowitz’s explanation for Susan’s initial denial and subsequent cover-up of the crime did not appear to ring true with the twelve jurors—especially after they heard the prosecutor describe her elaborate efforts to cover up the crime during his opening remarks. O’Connor pointed out that Susan cleaned and hid the knife used in the attack, got rid of her bloody clothing, and placed her husband’s car at the train station in an effort to cover her tracks. Those were hardly the actions of an innocent woman, he insisted.

The following morning, jurors boarded a bus for the Polk’s hillside residence to get their first look at the Miner Road crime scene. The group spent several hours viewing the pool area and the guesthouse where Gabriel found his father’s bloodied body.

That Wednesday, the jury heard from prosecution witnesses, among them the 911 operator who took Felix Polk’s call on October 6, exactly one week before the murder, to report that his wife had threatened his life.

“I remember the caller saying, ‘My wife threatened to kill me,’” police dispatcher Randee Johnson testified.

Another witness, Deputy Sheriff Shannon Kelly, one of the first officers on the scene, testified that Susan denied having done anything wrong during the ride to police headquarters on the night of October 14,2002. Although his role in the criminal investigation was limited, Kelly endured two hours of cross-examination by Horowitz, who was trying to cast doubt on police competence at the crime scene. This strategy proved lost on jurors, two of whom were overheard in the men’s room trying to figure out why Horowitz had spent so much time with Kelly. Apparently the men were unaware that defense lawyer, Ivan Golde, was also in the bathroom at the time.

“They didn’t see me,” Golde later complained to Judge Brady. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing.”

The judge denied Horowitz’s request to have the two jurors removed from the case, but warned the men to refrain from further discussion of the case. “I know this is not like what you see on TV, but it is important,” Judge Brady told the jurors.

O’Connor closed the first week of testimony with a victory, as the judge accepted into evidence the letter Susan wrote describing Felix’s alleged involvement with the Mossad. The defense was successful in convincing Judge Brady to admit a second letter that Susan wrote to her children in which she detailed the alleged abuse she suffered at the hands of Felix.

But the trial would take an unexpected turn when, four days into the case, Daniel Horowitz made a grisly discovery.

It was just before 6 PM on Saturday, October 15, when the lawyer punched in the security code for the locked gates barring entrance to his home at 1901 Hunsaker Canyon Road. He steered his red Honda S2000 up the winding dirt driveway. At the top of the remote hill was an expansive construction site, where Horowitz and his wife, Pamela Vitale, were building a lavish, seven-thousand-square-foot Italian-style mansion. Off to one side was a rundown trailer where the couple had been living with their dogs for nearly a decade while they oversaw the construction of their dream house.

Читать дальше