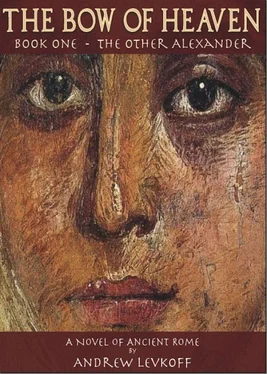

Andrew Levkoff - The other Alexander

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Andrew Levkoff - The other Alexander» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The other Alexander

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The other Alexander: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The other Alexander»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The other Alexander — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The other Alexander», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Andrew Levkoff

The other Alexander

Prolog

20 BCE — Summer, Siphnos, Greece Year of the consulship of Marcus Appuleius and Publius Silius Nerva

The boy comes bearing honeyed tea onto the blue tiled terrace with its too-white stuccoed walls. I shan’t call him ‘boy’ to his face, though, or risk forfeiting my foot massage. Say what he will, his scars are almost thirty years younger than mine. Though his were earned in battle and mine are of a different nature entirely, to me Melyaket will always be “boy.” Now he waits patiently for me to set down the stilus. I have long stopped trying to convince him that it is I who should serve him, for I know he will but smile thinly and ignore me as always. So be it. I am ancient and frail and the tea is hot and aromatic. Of course there is also the matter of my feet.

Enough of the Parthian bowman; how he and I came to this island sanctuary is a tale for another telling. This recounting does not belong to Melyaket, nor would I presume to lay claim to it for myself. This is my lord’s story, and I pray the gods grant me strength and time to tell it. My master is long dead; few mourned his passing; fewer still recall his name with kindness. More than thirty years have passed since his ignoble death in the dirt at the feet of his enemies. The memory of that heat-drenched day, encrusted with grime and blood and clouded by the dusty haze of battle yet returns to me with glittering clarity. His mocking Parthian captors, their barbarism and bloodlust palpable as they towered over him, pricked him with their taunts and jeers, swords poised to pierce his unarmored heart. Yet when the moment came, they were robbed of the release the mortal blow would have granted both murderers and murdered. For it was Melyaket who slew my lord.

There is much to tell. Nicias has sent men to scour the town for ink, reeds and parchment. I am anxious for their return, for these tablets are all but useless for my intention. It would take a forest of their frames to fill my need. I shall use them for my notes and musings. Now they sit before me, prepared with freshly melted wax, piled so high on my writing table that unless I rise from this cushioned chair, a feat for which I find I lack both the strength and the inclination, the splendor of the sea below, bronzed and burnished by the setting sun, can only wink at me between the cracks. I pull a simple string necklace from around my throat and find the single scallop shell that adorns it. With my thumb I absentmindedly rub its inside surface, grown glossy with age and use, admitting a rising tide of memory.

News has reached us from Rome: the standards of my master’s legions, pried from the twisted fingers of their fallen bearers and flaunted under the shamed chin of Rome for each day of their captivity have finally been ransomed, by no less a negotiator than Caesar Augustus himself. For thirty-five years they were held hostage behind the throne at Ctesiphon, the Parthian capital, a mockery of the invincibility of Rome. Though my body wrinkles and shrivels like a Persian peach forgotten in the desert sun, the memory of the day they were lost remains as ripe and raw as a newly drawn knife cut.

To the cruel and superstitious Roman, whether soldier or senator, these are more than poles covered in hide and metal, wood and bone. They are the very essence of Rome, imbued by the gods themselves with the divine mystery of its dominance and superiority. But to me they have always been absent and ironic reminders both of liberty and of loss. I care not, after all these years, that these eagle-festooned sticks have been returned to the bosom of Rome, a poisonous breast where I shall be pleased never to rest my head again.

Tulio writes that the return of the standards has caused such riotous celebration in the streets it is as though Parthia itself had been vanquished. The rabble’s ignorance is as supple and resilient as its memory is arthritic. And what of the nobles who cling with a slippery and tenuous grasp to the tether that holds the mob in check? They must remain blameless, their pristine togas unblemished by any crimson reminders of our misadventure.

PART I — Slave to Master

Chapter I

86 BCE — Summer, Rome Year of the consulship of Gaius Marius the Elder and Lucius Cornelius Cinna

If you are a citizen of Rome, you will not know the count of the year, because history, being a thing of the past, is of little interest to you. Rome concerns itself with today and tomorrow, but cares little for yesterday. So while we Greeks (the learned ones, that is) know that 690 years had passed since the first Olympiad, you Romans know only that which concerns you most: who is in power now. Which I suppose is a very modern, forward-looking attitude, for who can remember who was in charge seventy or eighty years ago? Should a Roman astound you with the ability to recall such a year, you may assume with some assuredness that some costly and bloody war was fought, a renegade noble took political matters into his own hands, or a rebellion of one sort or another was put down. Or perhaps a bit of each.

When I was little more than a boy, time had stopped altogether: the count of the year reset itself to 1, and would remain there the following year and the one after that, for so many turns of the calendar I cannot recall the count. Ah, invincible, immortal youth. You see, free men may make use of the passage of time as if each golden coin may forever be newly minted: lay plans, set goals, chart achievements. But never mind. However you set your clock, what I speak of now transpired sixty-six years ago. I was 19, about to be imprisoned for the next thirty-three years of my life, not in a cell, but to the will a single man.

My, Alexandros, you whine like a stuck boar. Reader, pay no attention to the sniveling of a melodramatic ancient who has outstayed his welcome above ground. I have had more than my fair portion of satisfaction and accomplishment. I have even known love. And as you see, I am quite accomplished in the art of digression. Move along, Alexandros, move along.

Who am I, you may protest, and with what credentials do I claim the right to chronicle the life of one of Rome’s once venerable patriarchs? I am no one. I am less than no one. But I was there through it all, and now I shall bear witness. You of breeding and substance, you senators and aristocrats may dismiss with a wave of your soft hands the thread of my narrative should it not unravel to your liking. Nonetheless, I shall tell what I know for truth’s sake and my master’s honor, and the glory of Rome be damned!

My name is Alexandros, son of Theodotos of Elateia. I may be bald, half-blind and more than a little wobbly on these eighty-five year-old willow branches that serve for legs, but my mind has yet to fail me; it is as keen today as the day I was made a slave of Rome.

Now there’s a dull word for you, commonplace and prosaic, like the chalky base coat of a mural, necessary to fortify the coming of the artist’s colorful strokes but ultimately invisible, its worth unseen. It is a word without bias or weight, like ‘water,’ or ‘tree.’ Unless you happen to be one. Then, the world becomes a simple but lopsided place. There are owners and there are the owned. And the latter, those afflicted with fits of common sense and introspection, must soon come to ask themselves in the black, sleepless hours, why? Why would the gods, in their unfathomable wisdom, give us life only to watch us fall to a state as low as this? What good could ever come of such a fate? There were those of us, I among them, who once blithely sought answers to the essence of being, who contemplated the meaning of existence with a pomposity only the truly ignorant may display. Without warning, the focus of our contemplation was wrenched from such esoteric heights and narrowed most effectively to the chafing sores of our ankle chains. The pursuit of knowledge is an inaudible whisper lost in the stentorian debate of an empty stomach, drowned out even by the quiet discourse of muffled sobs in the night.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The other Alexander»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The other Alexander» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The other Alexander» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.