A few nights before he was to be returned to Devil’s Island, Bougrat decided not to go back. Annette put up some money and they quickly spread it around. Next thing anyone knew, Bougrat’s little raft, equipped with a sail, had arrived at the shore along with seven burley prisoners from the penal colony to act as a crew.

And then he took off on August 30, 1928.

They began a sea journey that has become part of French prison folklore, encountering high winds, currents, storms and a dozen days when they were marooned on a mud bank. But eventually the boat found its way northward along the coast and eventually up the Orinoco River and into Venezuela. He eventually landed at the little town of Iripa. As fate would have it, the town was in the middle of an epidemic of dengue fever a nasty mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. There had already been fatalities.

Bougrat knew when he needed to go to work. He offered his expertise in medicine and treated patients with boundless dedication, although he was hit himself by the disease. He threw himself into his work for months, refusing to send for Annette until the epidemic had died down.

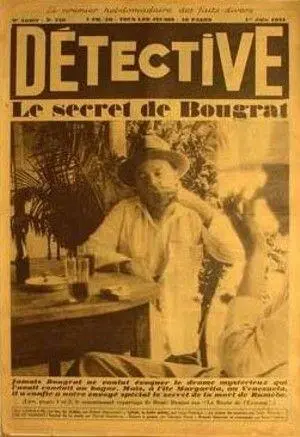

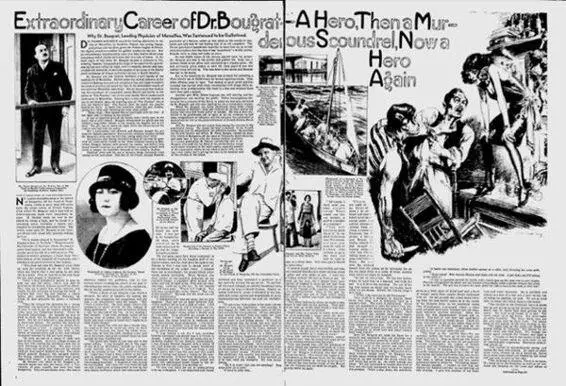

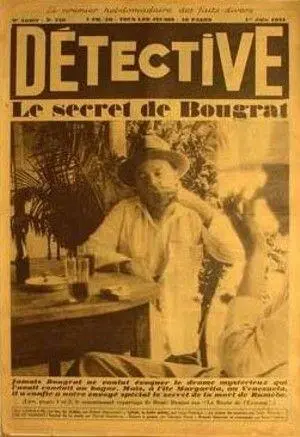

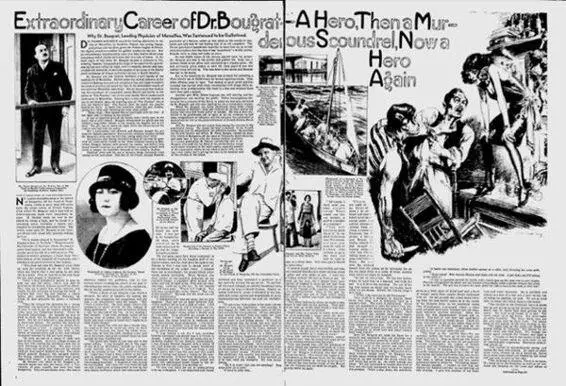

Meanwhile, French authorities had learned of his whereabouts and demanded his extradition, as well as those of his breakaway companions. But there was no extradition treaty between the two countries at the time. Pictures and stories began to appear in the French press about the dissolute doctor who had been condemned to Devil’s Island but was now living openly in South America.

Venezuela at the time was governed by an ornery strongman named Juan Vicente Gomez. His rule was absolute for decades and he was particularly cunning about juggling relations at home and abroad. But Gómez was also busy on other fronts. He never married but he had two beautiful mistresses by whom he had sixteen children. Gómez also fathered many other children in brief relationships, somewhere between sixty and ninety. So the strongman didn’t have a lot of time to ponder requests from distant foreign governments. Thus he decided that he would return the other escapees (some having had the stupidity to commit various new crimes) to French authorities. But Bougrat, the busy medical man, the emerging local hero, was useful. He could stay. Thereupon, Dr. Bougrat sent for Annette whom he eventually married.

Bougrat quickly learned that there was a shortage of physicians in Caracas. So he and Annette got married and set up a home, on her money, in the capital. Bougrat applied for a license to practice. The medical authorities in Venezuela declined to let him work in the capital but had no problem with him working out in the remote hinterlands. So Dr. Bougrat took a new look around for a soft landing.

He found one soon. Fully integrated in the country, now proficient in Spanish, married with two daughters, he settled in Margarita Island, a pleasant place off the mainland not too far from Caracas. He opened a small private hospital in the community of Juan Griego, never refusing to treat the needy for free. Comfortably, he sat out the Great Depression of the 1930’s as well as World War Two. Bougrat, with his sex problems solved right in his own home, didn’t do any chasing in Venezuela. His mind on his work, he soon gained the respect of his professional colleagues.

He also never stopped protesting his innocence of murder. He may have been guilty of many things back in France, he insisted, but killing his friend Rumèbe was not one of them.

(Dr. Bougrat in Venezuela with child believed to be his daughter, circa 1930.)

Eventually, those back in France began to listen. After the Second World War, he received a pardon and was invited to return. But he insisted that he had found happiness in South America and there was no need for a pardon since he hadn’t done what he had been convicted of. If his conviction had been set aside, it would have been one thing, he said. But a pardon was not something he would accept. Nor was he interested in leaving his remote island paradise. There he was known as “the miracle doctor” whom God had sent to look after the poor.

So he stayed on his island for thirty-eight years. He lived modestly but comfortably with his family and surrounded by an adoring community. He died in his new home in 1962 at the age of seventy-two.

Eight years later in 1970, a local committee of Venezuelans erected a monument on his tomb. The monument endures to this day, almost a full century after Dr. Bougrat’s Jekyll-Hyde existence in the south of France. Fresh flowers appear on the tomb in perpetuity, continuing remembrances from the people of Juan Griego whom Dr. Bougrat served in the better years of his life.

And now, a bonus track…

THE CASE OF ARSENIC, OLD LACE AND SISTER AMY ARCHER

The eerie sound of the hearse creaking to a stop in front of The Archer Home for old folks and chronic invalids in the ink-black pre-dawn hours of the steaming August night awakened the two old maids who lived in the snug brick house across the street.

“Heavens!” said Mabel Bliss to her sister, Patricia, as she drew the bedroom curtain aside and peered out. “That’s the third time somebody’s died over there in less than a month! And always in the middle of the night.”

A light went on in the vestibule of The Archer Home and the front door opened to admit two burly men who had jumped down from the driver’s seat of the death wagon, opened the rear door and dragged out a box six feet long. They weren’t inside very long when they reappeared with the box, which seemed to be more of a burden to carry now. They shoved it into the hearse and clattered into the gloom.

Now a light went on in the parlor and the Bliss sisters could see Sister Amy Archer, founder of the home bearing her name, wearing nothing but a very fancy nightgown, settling herself at a little organ. (The “Sister” was a title she had bestowed on herself. It had nothing to do with any religious order.) The windows were open and presently there wafted across the narrow street the sweet sad strains of Nearer, My God, To Thee, accompanied by Sister Amy’s pleasant soprano.

Sister Amy Archer, one of the few arch-murderess in criminal history who could quote passages from the Bible from Genesis to Exodus, was only half way through the hymn when a second figure appeared, a brooding giant of a man with a red puffy face and walrus moustache, in nightshirt and bare feet. This was Big Jim Archer, Sister Amy’s fifth spouse, a coarse type in his forties who seemed to be an odd sort of a mate for our heroine. Sister Amy, though in her late thirties, looked a good decade younger, and, though sharp-featured, was a very attractive little woman with snow-white skin, jet-black hair and a divine form that even the starch in her professional uniform simply couldn’t hide. Not that she was hiding much that August night after the hearse left, nor was Big Jim hid-ing anything, either, when the music stopped and the lights went out.

It was Sister Amy’s views on sex that puzzled the Bliss sisters. For somebody who was so devout and stern, and who was so unalterably opposed to alcohol and tobacco in any form, Sister Amy was simply mad about sex. Nor did she make any bones about it.

Читать дальше