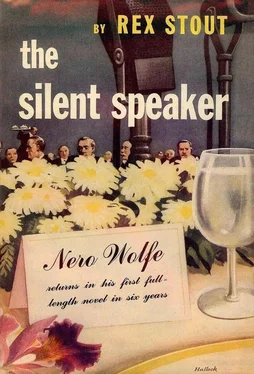

Rex Stout

The Silent Speaker

Seated in his giant’s chair behind his desk in his office, leaning back with his eyes half closed, Nero Wolfe muttered at me:

“It is an interesting fact that the members of the National Industrial Association who were at that dinner last evening represent, in the aggregate, assets of something like thirty billion dollars.”

I slid the checkbook into place on top of the stack, closed the door of the safe, twirled the knob, and yawned on the way back to my desk.

“Yes, sir,” I agreed with him. “It is also an interesting fact that the prehistoric Mound Builders left more traces of their work in Ohio than in any other state. In my boyhood days—”

“Shut up,” Wolfe muttered.

I let it pass without any feeling of resentment, first because it was going on midnight and I was sleepy, and second because it was conceivable that there might be some connection between his interesting fact and our previous conversation, and that was not true of mine. We had been discussing the bank balance, the reserve against taxes, expectations as to bills and burdens, one of which was my salary, and related matters. The exchequer had not swung for the third strike, but neither had it knocked the ball out of the park.

After I had yawned three more times Wolfe spoke suddenly and decisively.

“Archie. Your notebook. Here are directions for tomorrow.”

In two minutes he had me wide awake. When he had finished and I went upstairs to bed, the program for the morning was so active in my head that I tossed and turned for a full thirty seconds before sleep came.

That was a Wednesday toward the end of the warmest March in the history of New York. Thursday it was more of the same, and I didn’t even take a topcoat when I left the house on West Thirty-fifth Street and went to the garage for the car. I was fully armed, prepared for all contingencies. In my wallet was a supply of engraved cards reading:

ARCHIE GOODWIN

With Nero Wolfe

922 West 35th Street PRoctor 5–5000

And in the breast pocket of my coat, along with the routine cargo, was a special item just manufactured by me on the typewriter. It was on a printed Memo form and, after stating that it was FOR Nero Wolfe and FROM Archie Goodwin, it went on:

Okay from Inspector Cramer for inspection of the room at the Waldorf. Will report later by phone .

At the right of the typing, scribbled in ink, also my work and worthy of admiration, were the initials LTC.

Since I had got an early start and the office of the Homicide Squad on Twentieth Street was less than a mile downtown, it was only a little after nine-thirty when I was admitted to an inside room and took a chair at the end of a crummy old desk. The man in the swivel chair, frowning at papers, had a big round red face, half-hidden gray eyes, and delicate little ears that stayed close to his skull. As I sat down he transferred the frown to me and grunted:

“I’m busy as hell.” His eyes focused three inches below my chin. “What do you think it is, Easter?”

“I know of no law,” I said stiffly, “against a man’s buying a new shirt and tie. Anyhow, I’m in disguise as a detective. Sure you’re busy, and I won’t waste your time. I want to ask a favor, a big favor. Not for me, I’m quite aware that if I were trapped in a burning building you would yell for gasoline to toss on the flames, but on behalf of Nero Wolfe. He wants permission for me to inspect that room at the Waldorf where Cheney Boone was murdered Tuesday evening. Also maybe to take pictures.”

Inspector Cramer stared at me, not at my new tie. “For God’s sake,” he said finally in bitter disgust. “As if this case wasn’t enough of a mess already. All it needed to make it a carnival was Nero Wolfe, and by God here he is.” He worked his jaw, regarding me sourly. “Who’s your client?”

I shook my head. “I have no information about any client. As far as I know it’s just Mr. Wolfe’s scientific curiosity. He’s interested in crime—”

“You heard me, who’s your client?”

“No, sir,” I said regretfully. “Rip me open, remove my heart for the laboratory, and you’ll find inscribed on it—”

“Beat it,” he grated, and dug into his papers.

I stood up. “Certainly, Inspector, I know you’re busy. But Mr. Wolfe would greatly appreciate it if you’ll give me permission to inspect—”

“Nuts.” He didn’t look up. “You don’t need any permission to inspect and you know damn well you don’t. We’re all through up there and it’s public premises. If what you’re after is authority, it’s the first time Wolfe ever bothered to ask for authority to do anything he wanted to do, and if I had time I’d try to figure out what the catch is, but I’m too busy. Beat it.”

“Gosh,” I said in a discouraged tone, starting for the door. “Suspicious. Always suspicious. What a way to live.”

In appearance, dress, and manner, Johnny Darst was about as far as you could get from the average idea of a hotel dick. He might have been taken for a vice-president of a trust company or a golf club steward. In a little room, more a cubbyhole than a room in size, he stood watching me deadpan while I looked over the topography, the angles, and the furniture, which consisted of a small table, a mirror, and a few chairs. Since Johnny was not a sap I didn’t even try to give him the impression that I was doing something abstruse.

“What are you really after?” he asked gently.

“Nothing whatever,” I told him. “I work for Nero Wolfe just as you work for the Waldorf, and he sent me here to take a look and here I am. The carpet’s been changed?”

He nodded. “There was a little blood, not much, and the cops took some things.”

“According to the paper there are four of these rooms, two on each side of the stage.”

He nodded again. “Used as dressing rooms and resting rooms for performers. Not that you could call Cheney Boone a performer. He wanted a place to look over his speech and they sent him in here to be alone. The Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf is the best-equipped—”

“Sure,” I said warmly. “You bet it is. They ought to pay you extra. Well, I’m a thousand times obliged.”

“Got all you want?”

“Yep, I guess I’ve solved it.”

“I could show you the exact spot where he was going to stand to deliver his speech if he had still been alive.”

“Thanks a lot, but if I find I need that I’ll come back.”

He went with me down the elevator and to the entrance, both of us understanding that the only private detectives hotels enjoy having around are the ones they hire. At the door he asked casually:

“Who’s Wolfe working for?”

“There is never,” I told him, “any question about that. He is working first, last, and all the time for Wolfe. Come to think of it, so am I. Boy, am I loyal.”

It was a quarter to eleven when I parked the car in Foley Square, entered the United States Court House, and took the elevator.

There were a dozen or more FBI men with whom Wolfe and I had had dealings during the war, when he was doing chores for the government and I was in G-2. It had been decided that for the present purpose G. G. Spero, being approximately three per cent less tight-lipped than the others, was the man, so it was to him I sent my card. In no time at all a clean efficient girl took me to a clean efficient room, and a clean efficient face, belonging to G. G. Spero of the FBI, was confronting me. We chinned a couple of minutes and then he asked heartily:

Читать дальше