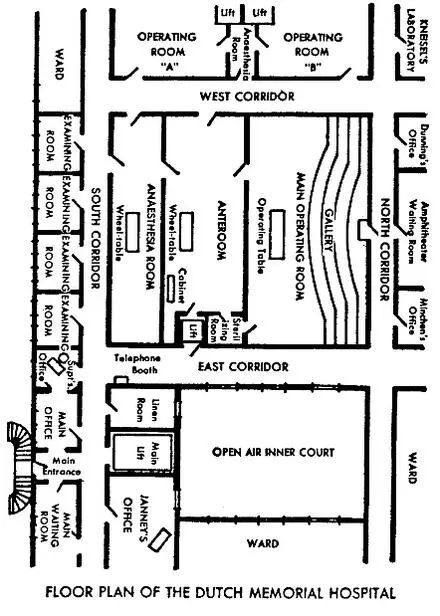

“Janney’s office is down there,” said Minchen, shrugging. “Queer sort of cuss, isn’t he, Ellery? But as great as they come... Let’s go back to my office. There’s still a good quarter of an hour before the operation.”

They turned the corner and walked with leisurely steps up the West Corridor.

“Reminds me of a bird, somehow,” said Ellery thoughtfully. “They way he holds his head, keeps darting those avian eyes of his about... Interesting little fellow. About fifty, isn’t he?”

“Thereabouts... Interesting in more ways than one, Ellery.” Minchen spoke boyishly. “There’s one medical man who’s really devoted his life to his profession. He’s spared neither himself nor his personal fortune. I’ve never known him to refuse a case on grounds of a small fee. In fact he’s done scores of jobs for which he never saw a cent, and didn’t expect to... Don’t get him wrong, Ellery; you’ve just met a genuine personage.”

“If what you said about his relationship with Mrs. Doorn is true,” commented Ellery, smiling, “I don’t suppose Dr. Janney has much to worry about financially.”

Minchen stared. “Why, how did you—? Well, of course,” he chuckled sheepishly, “it’s probably evident. Yes, Janney is due for a whacking big legacy on Abby’s departure from this world. Everybody knows that. He’s been quite like a son to her... And here we are.”

They had reached Minchen’s office. Minchen telephoned briefly, seemed satisfied with what he heard.

“They have Abby in the Anteroom already,” he stated, putting down the instrument. “They got her blood sugar down to 110 milligrams — it’s a question of minutes now. Well, I’ll be glad when it’s over.”

Ellery shivered slightly. Minchen pretended not to notice. Over cigarettes, they sat in silence; an indefinable gloom hovered between them.

With an effort Ellery shrugged his shoulders and exhaled a cloud of smoke. “About this co-authorship, John,” he said lightly. “I never suspected that you’d succumb to the writing bug. What’s it all about?”

“Oh, that” Minchen laughed. “Most of the work is bound up with actual case histories, proving a theory which both Janney and I hold in common; and it is possible to predict the predisposition to specific ailments of embryos by careful analysis of congenital influences. Complicated?”

“Overwhelmingly scientific, professor,” murmured Ellery. “How about letting me peep at the manuscript? I might be able to give you a few pointers in a literary way.”

Minchen flushed. “Thunder! Can’t do that, old son,” he said awkwardly. “Janney’d have my life. As a matter of fact, both the manuscript and the case records we are using in the book are kept absolutely private; Janney guards ’em as jealousy as his life. Why, the old man recently cashiered an interne who had the unhappy impulse to root around in Janney’s filing-cabinet — merely out of academic curiosity, I suppose... Sorry, Ellery. The only people who can see those records are Janney, myself and Miss Price, Janney’s assistant — she’s a trained nurse — and she does only the routine clerical work.”

“All right, all right!” grinned Ellery, closing his eyes. “I surrender. I just wanted to help you, you blamed old codger... Of course you remember your Iliad? ‘Light is the task when many share the toil.’ If you spurn my assistance...”

They laughed together.

Ellery Queen, dilettante of criminology, had no stomach for blood. Raised on stories of crime, fed with tales of murder, in daily contact with desperadoes and manhunters, he nevertheless endured the sight of maltreated flesh with difficulty. His position as son of a policeman; his association with brutality and warped minds; his own literary dabblings in the mire of criminal psychology — these had not inured him to the reeking evidences of man’s inhumanity to man. On the scene of a slaughter his eyes were keen, his judgment swift, but always his heart was sick...

He had never attended a surgical operation. Dead bodies he had seen galore; mangled corpses in morgues, fished out of rivers and the sea, huddled on railroad tracks, lying still in the streets after gang-fights — of death at its unprettiest he had bitter and plentiful knowledge. But chilled steel biting into warm flesh, cutting through live tissue, severing veins through which red blood spurted — the thought nauseated him.

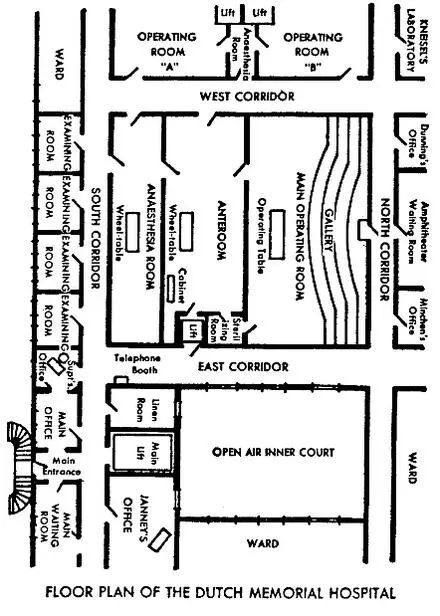

It was with a sensation of mingled dread and excitement, then, that he took his seat in the gallery of the Dutch Memorial Hospital Amphitheater, eyes glued on the scene of calm noiseless activity being enacted twenty feet away in the orchestra of the theater. Dr. Minchen lolled in a chair by his side, quick blue eyes missing nothing of the preparations for the operation... A whisper of conversation came dimly to their ears from a group of people seated about them in the gallery. Directly in the center was a handful of white-garbed men and women — internes and nurses gathered to watch the professional handiwork of the surgeon. They were very still. Behind Ellery and Dr. Minchen sat a man, also in hospital regalia, and a fragile-looking young woman in white who whispered intermittently in his ear. The man was Dr. Lucius Dunning, Chief Internist; the girl his daughter, attached to the Social Service Department of the institution. Dr. Dunning was grey, with a startling seamed face from which mild brown eyes peered. The girl was fair and unhandsome. There was an appreciable tic in one eyelid.

The gallery rose from the floor of the theater, separated from the orchestra by a high impassable barrier of white wood. The rows of seats ascended steeply toward the rear — much as in the balcony of a theater for the drama. At the rear wall was a door, opening outward on a circular staircase which led to the floor below and gave directly on the North Corridor.

The sound of footsteps now became audible, the door swung open, and Philip Morehouse stepped nervously into the gallery, his eyes roving. His brown overcoat and hat had disappeared. Spying the Medical Director, he ran down the stepped ramp and bent over to whisper into Minchen’s ear.

Minchen nodded gravely, turned to Ellery. “Meet Mr. Morehouse, Ellery — Mr. Queen.” He waved his fingers. “Mrs. Doorn’s attorney.” The two men shook hands; Ellery smiled mechanically, turned back to watch the orchestra.

Philip Morehouse was a lean man with steady eyes and a stubborn jaw. “Hulda, Fuller, Hendrik Doorn — they’re downstairs now in the Waiting Room. Can’t they possibly be present during the operation, Doctor?” he whispered urgently. Minchen shook his head. He indicated the seat next to him. Morehouse frowned, but sank into the chair and instantly became absorbed in the movements of the nurses below.

An old man in white shuffled up the steps, peered into the gallery, caught the eye of an interne, nodded violently, and at once disappeared. The click of the lock in the door held a note of finality. For an instant the old man could be heard rustling about behind the door; then even the sound of his movements died.

The orchestra of the Amphitheater had settled down now to a hushed expectancy. Ellery thought it very like the moment in a legitimate theater just before the rise of the curtain, when the audience holds its breath and absolute quiet descends on the house... Under a triple brace of electric globes of immense size, emitting a cold, steady and brilliant light, stood an operating-table. It was denuded, pitiless in its lack of color. Near it was a table stacked with bandage, antiseptic cotton, small bottles of drugs. A glass-covered case of shining, wicked-looking steel instruments was being watched over by an interne, who kept sterilizing them in a compact little machine at his right hand. At one side of the room two white-gowned surgical assistants — men — stood over porcelain bowls carefully washing their hands in a bluish fluid. One imperiously reached for a towel handed him by a nurse; he dried his hands quickly and on the instant bathed them once more, this time in a watery-looking fluid.

Читать дальше