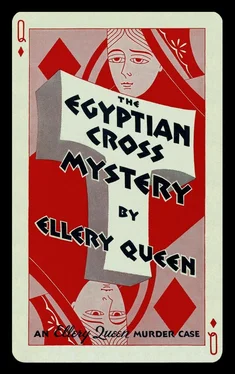

Ellery Queen

The Egyptian Cross Mystery

Ellery Queen — The cosmopolitan, pince-nezed special investigator knew his logic could solve anything, but he had trouble making sense out of T squares

Andrew Van — The withdrawn, correct schoolmaster lived a quiet life in Arroyo, hiding more from the town than his money-stuffed mattress

Ol’ Pete — The slightly daffy, rag-clad hillman lived behind barbed wire because he liked privacy, but his primed shotgun guarded something else

Harakht — The shaggy-bearded Healer of the Weak led a flock of naked disciples to salvation and kept solvent by selling “elixir of youth” — a possibly lethal brew

Velja Krosac — The “furrin’-looking” vendettist was the No. 1 suspect. The limping man appeared at every murder scene

Professor Yardley — Ellery’s old prof joined a country-wide search that led him far from the Halls of Ivy and had him learning lessons from his famous student

Margaret Brad — The well-cushioned but handsome matron couldn’t offer any information about her husband — she was more concerned about her future than his past

Helene Brad — Margaret’s lovely daughter kept a suitor on land and another at sea, then both came running without an S.O.S.

Jonah Lincoln — The lean, levelheaded New Englander had one eye on Helene and the other on money. He might have won both, but his employers lost their heads

Paul Romaine — The tanned, well-muscled Adonis had a string of women, but the police were more interested in his male associates

Hester Lincoln — Jonah’s plain-faced sister with a not-so-plain body left her clothes trailing from Bradwood to the Island nudist colony, but she was conventional about one thing — murder

Victor Temple — The retired army doctor pursued his lady-love during the day and eavesdropped under open windows at night

Stephen Megara — The globe-trotting yachtsman hesitated to reveal his past — it could only shorten his future

There is one minor mystery connected with the various major mysteries of The Egyptian Cross Mystery and that is a puzzle which has little, if anything, to do with the story itself. It might properly be called “the mystery of a title.” It was brought to my attention by the author himself — my friend, Ellery Queen — in a note appended to the manuscript, which he had sent on from his little place in Italy after urgent solicitations by cable from his very devoted servant.

The note said, among other things: “Give ’em hell, J. J. This isn’t the usual claptrap on le crime égyptologique. No pyramids, no Coptic daggers in the midnight dark of a creepy museum, no fellahin, no Oriental pooh-bah of any sort... in fact, no Egyptology. Why, then, The Egyptian Cross Mystery, you ask? With, I admit, justification. Well, the title is provocative, for one thing; it positively magnetizes me. But if there’s no Egyptian significance! Ah, there’s the beauty of it. Wait and see.”

Typical Elleryana, observe; which, as Ellery’s readers are apt to know, are always interesting and often cryptic.

The investigation of these appalling murders was one of my friend’s last jobs. It is the fifth Ellery Queen case to be presented to the public in fiction form. It is composed of extraordinary elements: a peculiar and unbelievable concoction of ancient religious fanaticisms, a nudist colony, a seafarer, a vendettist from the hotbed of Central European superstition and violence, an oddly mad “reincarnated god” of Pharaonic Egypt... on the surface a potpourri of impossible and fantastic ingredients; in actuality the background of one of the most cunning and horrible series of crimes in modern police annals.

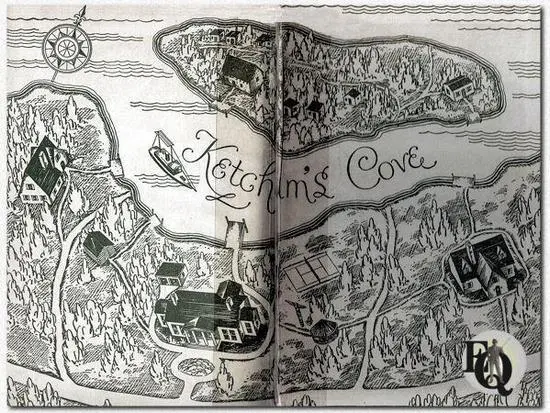

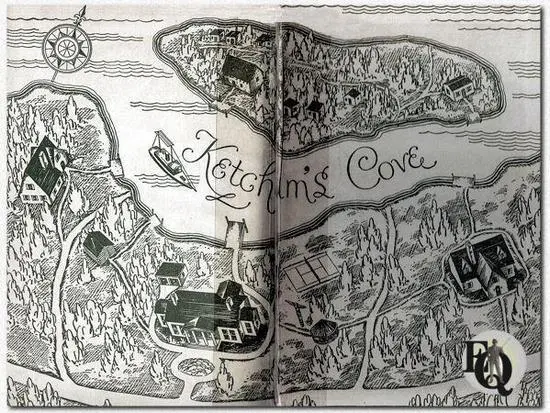

If you are disappointed at the absence of that rare old codger of a manhunter, Inspector Richard Queen — I always insist that Ellery doesn’t half do his father justice — let me reassure you. He will be back. In The Egyptian Cross Mystery, however, Ellery played a peculiarly lone hand, due to certain geographical ramifications of the case. I was tempted to request the publisher to recommend an atlas as supplementary reading to this novel, or to issue as the frontispiece a map of the United States. It began in West Virginia...

But there I go. After all, this is Ellery’s story. Let him tell it.

J. J. McC.

RYE, N.Y.

August, 1932

Part One

Crucifixion of a Schoolmaster

“A working knowledge of psychiatry has been of invaluable assistance to me in my profession of criminology.”

— Jean Turcot

It began in West Virginia, at the junction of two roads half a mile out of the little village of Arroyo. One was the main road from New Cumberland to Pughtown, the other a branch leading to Arroyo.

The geography, Ellery Queen saw at once, was important. He saw many other things in that first glance, too, and felt only confusion at the contradictory nature of the evidence. Nothing matched. It was necessary to stand off and think.

How Ellery Queen, a cosmopolite, happened to be standing beside a battered old Duesenberg racing car in the muddy cold of the West Virginia panhandle at two o’clock post meridiem of a late December day requires explanation. So many factors contrived to bring about this extraordinary phenomenon! One — the primary one — was a busman’s holiday instigated by Inspector Queen, Ellery’s father. The old man was knee-deep in what might be termed a policemen’s convention; affairs in Chicago as usual were wretched, and the Commissioner had invited prominent police officials from major cities to lament with him the deplorable lawlessness in his bailiwick.

It was while the Inspector, in rare fettle, was scurrying from his hotel to Chicago’s police headquarters that Ellery, who had accompanied him, learned of the puzzling crime near Arroyo — a crime which the United Press piquantly dubbed “The T Murder.” There were so many elements of the newspaper accounts which titillated Ellery — the fact, for example, that Andrew Van had been beheaded and crucified on Christmas morning! — that he peremptorily yanked his father from the smoky Chicago conferences and headed the Duesenberg — a second-hand relic capable of incredible speed — eastwards.

The Inspector, although a dutiful father, immediately surrendered his good humor, as might have been expected; and all the way from Chicago — through Toledo, through Sandusky, through Cleveland, Ravenna, Lisbon, a host of Illinois and Ohio towns, until they came to Chester, West Virginia — the old man maintained a threatening silence, punctuated by Ellery’s sly monologues and the roar of the Duesenberg’s exhaust.

They were through Arroyo before they realized they had been in it; a tiny place of some two hundred souls. And... the junction.

The signpost with its crossbar at the top was visible in stark silhouette for some distance before the car rolled to a stop. For the Arroyo road ended there, meeting the New Cumberland-Pughtown highway at right angles. The signpost therefore faced the exit of the Arroyo pike, one arm pointing northeast to Pughtown, the other southwest to New Cumberland.

The Inspector growled: “Go on. Make a fool of yourself. Of all the dumb poppycock! Hauling me down here... just another crazy murder... I won’t be—”

Ellery switched off the ignition key and strode forward. The road was deserted. Touching the steel sky above posed the mountains of West Virginia. Underfoot the dirt was cracked and stiff. It was sharply cold, and a keen wind blew the tails of Ellery’s overcoat about. And ahead stood the signpost upon which Andrew Van, eccentric schoolmaster of Arroyo, had been crucified.

Читать дальше