But when, on reading the diary, I discovered the awful facts surrounding Hulda’s birth... Inspector, can you blame me for withholding the information and destroying the diary? Not for myself — the shame means nothing to me — but think of what it would mean to such an untainted young girl as Hulda to have the world know that she is the illegitimate child of her own housekeeper.

There is only one other item in this connection... which may be verified by consulting the will now filed for probate. That is, that Hulda inherits the major portion of the Doorn estate with no reservations of birth or parentage, but rather as the legal daughter of Abigail Doorn, which she is. Her true parentage can in no way affect the bequest to her. Consequently, my reticence regarding the whole shameful story cannot be construed as having been animated by selfish motives, such as might be ascribed to me if Hulda’s inheritance hinged upon her being a blood relation of the deceased...

Mr. Queen was also correct in his surmise that Abigail and Sarah Fuller quarreled incessantly over the secret of Hulda’s birth. The diary stated specifically that Sarah had regretted her bargain, and that she was perpetually threatening to disclose her motherhood unless the girl were returned to her. With the passage of the years Abigail had grown to regard Hulda with genuine maternal love; and it was only her fear that Sarah would tell the story to the world that prevented her from discharging the middle-aged and by now fanatical woman in her employ.

Since the death of Mrs. Doorn I have confidentially spoken with Sarah Fuller and have received her positive assurance, now that Abigail — the object of her hate — is dead, and that I, whom for no reason that I can see she likes, am to marry Hulda — that she will not reveal the secret Dr. Dunning for selfish reasons may be depended upon to keep his mouth shut; his entire career and reputation depend upon his silence.

It is not difficult to guess, as Mr. Ellery Queen did, that it was this matter of Hulda’s parentage and the course they should adopt which caused Sarah Fuller to seek out Dr. Dunning at various times in the past few days. Strangely enough, she bears him no ill will. The crazy whims of a crazy woman! She told me yesterday that they discussed the matter from every angle; and with a shy pride announced that Dunning had persuaded her to let the girl live out her life thinking she was a Doorn.

Another matter disclosed by the diary was important in that it described Dr. Janney’s part in the affair. As you may or may not be aware, Dr. Janney was Mrs. Doorn’s confidant at all times; particularly since he was one of the handful who knew the real facts of Hulda’s birth. Dr. Janney’s attitude, the diary stated in one place, toward Dunning was quite unaffected by his knowledge of Dunning’s virtual rape; it seems that Dunning got by with the worldly view that a man may be forgiven sowing his wild oats. At any rate, Janney often upbraided Sarah for her trouble-making propensities, her willingness to ruin Hulda’s life merely to satisfy her own thwarted maternal instincts. Queer, isn’t it? Perhaps his broad-minded attitude toward Dunning was due to his honest admiration of Dunning’s ability professionally and his own sophistication.

In every sense of the word, Dr. Janney was a friend of Mrs. Doorn’s. He defended her every action; there was never the slightest hint of disaffection or disloyalty between them.

Please pardon me if I renew my plea for your silence. Not for myself; I think you know that. But for the sake of Hulda, who to me is everything worth living for.

Sincerely,

PHILIP MOREHOUSE.

P.S.: I should greatly appreciate your destroying this letter, of which there are no duplicates, as soon as you have read it.

P.M.

The only other incident of that serene Friday which Inspector Queen afterward had reason to recall, was a telephone message for Ellery Queen at 6:30 Friday evening.

Ellery’s attitude in the past twenty-four hours had subtly altered. He no longer chafed, nor did he pace the floor with the fierce absent energy which had characterized his movements during the hectic days before.

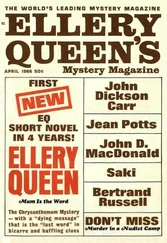

All day Friday he remained at the living-room window, reading and, for one interval of two hours, typing at his creaky, cranky old machine. Inspector Queen, who flew into the apartment at noon for a hasty luncheon and a telephone consultation with various subordinates at Headquarters, peered over his son’s shoulder and saw that Ellery was writing away at a detective novel — one which had been begun long months before but which had been tossed aside and neglected during a fitful period enduring for weeks. [7] The manuscript of Murder of the Marionettes, one of the detective stories Ellery wrote under his own name. — J. J. McC.

The old man grunted, but there was a smile beneath his grey mustache. It was a good sign. He had not seen his son wear such an air of detachment and peace in many moons.

The eventful telephone call came just after the Inspector had reappeared in the apartment after another barren afternoon. Lines of discouragement lengthened his face. They dissolved and his features stiffened into an intent mask as he heard Ellery’s voice from the bedroom.

It was an excited voice — a fresh and joyous voice — such a voice as Ellery employed only at rare intervals.

The Inspector closed the outer door softly and stood listening, scarcely breathing.

“Pete! Where are you?” At first there was a note of anxiety. Then the voice deepened, grew gay. “Marvelous! Marvelous, Pete! Connecticut, eh? Reasonable enough... Hard time? Well, no matter... Good man! Guard it with your life. You got the paper? Great!... Well, no. Make a copy and let me have it the moment you return to town — three o’clock in the morning, if necessary. I’ll be waiting up for you... Right. Hurry!”

The Inspector heard the crash of the receiver and Ellery’s strong voice shouting, “Djuna! It’s over!”

“What’s over?” demanded the old man as Ellery bounded into the living-room.

“Oh, dad!” Ellery grasped his father’s arm and shook it gently. “My case is complete. Finis. Pete Harper—”

“Pete Harper, eh?” The Inspector was grim. Lines of fatigue bordered his old mouth. “And if you had work for somebody, why didn’t you let my boys take care of it?”

“Now, dad,” chuckled Ellery, forcing the old man into the armchair, “you should know better than to ask that question. There was a reason — case wasn’t complete. And I didn’t want the official mark on the work Pete did for me. If it hadn’t worked out there would have been a lot of explaining to do...

“It’s all over but the shouting. When Pete gets here tonight and delivers to me that very interesting document... A leetle more patience, sire.”

“All right, son.” The old man looked tired. He lay back in the chair and closed his eyes. “I’m due for a rest...” The wise old eyes flew open. “You didn’t seem particularly pleased about these murders twenty-four hours ago.”

Ellery raised his long arms in mock adoration of an invisible idol. “But I wasn’t successful then!” he cried. “And to-day I am. For — to quote the irrepressible Disraeli — ‘Success is the child of audacity’ — and I have been so audacious in my reasoning, good father, as even you would not believe... Hereafter I’ll follow as a blessed rule the Gallic precept of Toujours Audace!”

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Argumentation

Always, toward the climax of a case, the tension which the Queens inevitably experienced communicated itself to the atmosphere of their apartment. It was something in the air — an effluvium of excitement which they neither controlled nor concealed, revealing itself in the jumpiness of Djuna, the silent irritability of the Inspector, the vigorous certainty of Ellery.

Читать дальше