“Theilman phoned his wife about eight?” Mason asked.

“Yes.”

“Did he use your office phone?”

“No. We were leaving a restaurant. He used a phone booth.”

“Did you hear the conversation?”

“No.”

“How do you know he phoned his wife?”

“He said he was going to phone her and went to the phone booth.”

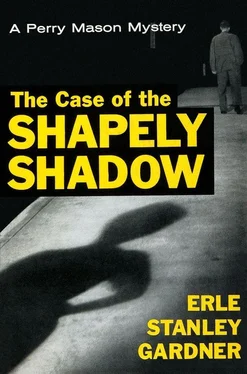

“Let’s go back to this shapely shadow,” Mason said. “You were at your office window?”

“Yes.”

“You watched Theilman after he came in sight?” Mason asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Then you saw the shadow of this young woman?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And you say that after she became visible, that is, after she had moved out into your line of vision, you continued to watch her until she vanished around the corner?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And she was about how far behind Mr. Theilman?”

“I would say twenty feet.”

“Now, let’s approximate the distance on this diagram. How wide is this street, do you know?”

“I think it is sixty feet.”

“And the sidewalks are about how wide?”

“Oh, perhaps ten feet.”

“So that would be a distance of eighty feet across the street.”

“Yes.”

“That is in a straight line, however. On a diagonal the distance would be greater.”

“Yes.”

“How much greater?”

“Oh, perhaps... perhaps a hundred and twenty feet.”

“Now,” Mason said, “you have testified that you watched Mr. Theilman cross the street and lost sight of him when he went around the corner where the building obstructed your view.”

“That’s right.”

“But you have also testified that you were watching this young woman from the time you first saw her, and evidently you saw her when Theilman had covered only some twenty feet of the distance. Now, which were you watching, the young woman or Theilman?”

“I was watching them both.”

“On whom were your eyes focused, Theilman or the woman?”

“On... well, I guess sort of in between them.”

“Then you weren’t watching the woman?”

“I was watching her but my eyes weren’t focused on her.”

“And you weren’t watching Theilman?”

“I was watching him but my eyes weren’t focused on him.”

“In other words, while a good-looking woman with a seductive figure was crossing the street, you didn’t look at her but kept your eyes focused at a point approximately ten feet ahead of her?”

“Well... No, I guess that’s not right. I... I was looking back and forth at both of them.”

“Can you describe this woman’s walk?”

“It was very graceful, very sinuous, very... well, hippy.”

“And you took your eyes off that seductive walk, off that graceful glide, off those swaying hips in order to watch Theilman, who was some twenty feet ahead of her?”

“Well, no,” Troy admitted. “When you come right down to it and put it that way, Mr. Mason, I don’t think I did. I kept my eyes on the girl.”

“Then you were mistaken in saying that you were watching Theilman?”

“Yes. I saw him generally but I was watching the girl. My eyes were on her.”

“Then you were completely mistaken in stating that your eyes were focused at a point midway between the young woman and Theilman?”

“I hadn’t given it any thought when I answered that question, Mr. Mason.”

“In other words, you answered a question while you were under oath without thinking?”

“Well, I guess I did.”

“And so gave a wrong answer?”

“Yes, sir, I did. I must have.”

“Thank you,” Mason said, with exaggerated politeness. “I was quite satisfied you had. Were there any other questions you were asked which you answered without thinking?”

“No.”

“You’re thinking now?”

“Yes.”

“That is all,” Mason said.

“I will call Mrs. Morley L. Theilman to the stand,” Ruskin said.

The second Mrs. Theilman, attired in black, her eyes demurely downcast, moved slowly forward, held up her right hand and was sworn and took her place on the witness stand.

Ruskin’s voice as he questioned the witness held that note of synthetic sympathy which is the stock-in-trade of some prosecutors examining bereaved widows.

“Mrs. Theilman,” Ruskin said, “we have to perform the disagreeable duty of identifying the decedent. You are the widow of Morley L. Theilman and you were, I believe, called upon to identify his body after it had been found in the place referred to generally as the Palmdale subdivision?”

“That is right,” she said.

“You saw the body?”

“I did.”

“Can you identify it?”

“Yes, it was the body of my husband, Morley L. Theilman.”

“Now then,” Ruskin went on, “directing your attention to Tuesday, the third — that would be the day before the body was found — can you tell us about the time you last saw your husband, where he was and what he did?”

Slowly and in a low voice, the witness described how Theilman had returned from his office, stated that he wanted to go to Bakersfield; that he asked for a fresh suit of clothes; that while he was in the bathroom shaving she had gone through the pockets of the discarded suit, had found the threatening letter and the envelope in which it came, and had read the printed demand for money, then had put the letter and envelope in the pocket of the fresh suit that her husband was going to wear.

“And was this the suit that he was wearing at the time of his death?” Ruskin asked.

“It was,” she said.

“You may cross-examine,” Ruskin said.

Mason rose, walked a few paces toward the witness stand and stood facing the slender woman with the downcast eyes.

“Mrs. Theilman,” he said, “where did you first meet your husband?”

“In Las Vegas, Nevada,” she answered in a low voice.

“What were you doing at the time?”

“Objected to,” Ruskin said, “as incompetent, irrelevant and immaterial, not proper cross-examination. It makes no difference what she was doing. It makes no difference when she met the decedent or how she met him.”

“I think I will overrule the objection,” Judge Seymour said. “In a case of this sort I certainly intend to give the defendant every latitude in the field of cross-examination. Counsel undoubtedly has some point in mind or he wouldn’t have gone into this. You may answer the question.”

“I was working in a rather varied capacity.”

“Describe the varied capacities,” Mason said.

Her voice grew a little stronger. Her eyes raised long enough to flash a glance of gathering animosity at Mason. “I guess the best way to describe it is to say that I was a show girl.”

“You showed yourself in bathing suits, did you not?”

“At times, yes.”

“You were a hostess?”

“Yes.”

“A shill?”

“I don’t know what you mean by a shill.”

“You put on daringly cut evening gowns that were tight and clinging and circulated around the gambling tables?”

“All evening gowns that are any good are tight and clinging,” she said.

“And yours was tight and clinging?”

“Yes.”

“And you circulated around the gaming tables?”

“Yes.”

“And made yourself easy to pick up?”

“I wasn’t picked up.”

“We’ll put it this way,” Mason said. “It was easy to get acquainted with you?”

“I was a hostess.”

“And, as such, it was easy to get acquainted with you?”

“I was simply doing my duty as a hostess.”

“It was easy to get acquainted with you?”

“I suppose so.”

“You made it that way?”

“If you want to put it that way, yes.”

Читать дальше