She turned to face the judge and said, “I don’t suppose you’ll ever understand, but that’s the way it was. Leslie ran away from me and came down here to El Templo. It took me two or three days to find out where he’d gone. I came on down to join him. He told me that he was here on a business matter, and I couldn’t be with him, that it would ruin things if I should try to make trouble. Well, I found there was a vacant apartment next to his, and I moved in. I guess he really was working on a case, and...”

“Never mind what you guess,” District Attorney Copeland interrupted. “Just answer Mr. Mason’s questions, Miss Cromwell. If the Court please, I submit that this witness shouldn’t be allowed to make a statement of this nature. She should only answer the questions which are asked her on cross-examination.”

Judge Meehan leaned forward to regard the young woman. “Are you explaining the contradiction in your testimony, Miss Cromwell?” he asked.

“Yes, Judge.”

“Go right ahead,” Judge Meehan said.

She said, “Then Leslie told me that if I’d be a good girl and not rock the boat, that within a week or so we could go away and travel anywhere we wanted to. We could go down into Mexico or South America, or anywhere. He said that he was going to have lots of money and...”

“I’m not particularly concerned with what he said,” Judge Meehan broke in to say. “I want to know how it happened that you falsified a portion of your testimony and whether that is the only part in which you failed to tell the truth.”

“Well,” she said. “I’ve got to explain this so you’ll understand. Leslie told me the night he was killed that his business was all ready to close up, but that Sally Elberton was coming down to see him. He told me I’d been all wet about her. He said that his relationship with her had been built up just so he could get some information. That he’d been working on her so he could put across this deal. He said she was a vain, empty-headed little brat, and he had to kid her along in order to keep on getting information out of her.”

“Were you over in Leslie Milter’s apartment that night?” Judge Meehan asked.

“Well — yes. I was. I went over to have a talk with him, and he was fixing me a hot buttered rum. He didn’t expect Sally Elberton until right around midnight. Then the doorbell rang, and he got sore and said, ‘I gave that little brat keys to my apartment so she wouldn’t have to stand out in front of it ringing a bell with all the world to see. I suppose she’s lost her keys. You skip over to your apartment, and within half or three-quarters of an hour I’ll give you a signal that the coast is clear.’”

“What did you do?” Mason asked.

“I went out the back door and across to my apartment. I heard him lock the back door after I left. Then I heard him going toward the front of his apartment.”

“Did you look to see who was coming into the apartment?”

“No, sir, I didn’t. She’d have been in by the time I got to my window, anyway. I went in, sat down and listened to the radio.”

“Then what?”

“After a while I began to get nervous and just a little suspicious. I tiptoed out to the back porch, and I couldn’t hear a thing; then I put my ear to the wall and I thought I could hear someone moving around very quietly. Then I thought I heard voices. Well, I made up my mind I’d go and stand at the window and look down at the door and see exactly when she left. I went into the front room and stood by the window. I saw there was a car parked in front of the apartment, and then this man” — she pointed to Witherspoon — “came out and got in the car. I didn’t know that he was expecting any man, and I thought perhaps it might have been an officer.”

“Why an officer?” Mason asked.

She said, “Oh, I don’t know. Leslie was inclined to take chances at times. I — well, he’d had some trouble. Anyway, I took down the license number.’

“And then what?” Mason asked.

She said, “I thought I’d go down and ring Leslie’s bell. I thought that would make him come to the door, and anyone that was upstairs would remain upstairs. I–I wasn’t dressed, just had a robe on over some underthings. So I went back into my bedroom and dressed. Well then, I thought I’d try to peek in through the window in the back door. So I went out to the back porch again, climbed over the rail, and gently tried the back door. It was locked. There was a little diamond-shaped glass window up near the top. By standing on tiptoe, I could look through it. I could see that the kitchen was pretty well filled with smoke. I dragged a box over, and stood on it and looked through the diamond-shaped window. I could see a man’s feet with the toes pointed up, and could see that the pan of sugar and water had boiled dry. I pounded on the door, and got no answer. I tried the knob, and the door was locked. Well, I moved the box back, climbed over the porch rail, back to my apartment, and went downstairs as fast as I could. You were ringing the bell of his door, and so I didn’t dare to show too much interest, or try to force my way in. As soon as I could get away from you, I walked down the street and telephoned the police that something was wrong up at Leslie Milter’s apartment. Then I went to the bus depot, and waited — and so help me, that’s the truth and every bit of it.”

Judge Meehan looked down at Perry Mason. “Any further questions?” he asked.

“None, Your Honor,” Mason said.

District Attorney Copeland answered the judge’s inquiry by a somewhat dazed shake of his head.

“That’s all,” Judge Meehan told the witness. “You are excused.”

It wasn’t until she heard the kindly note in his voice that Alberta Cromwell burst into tears. Sobbing, she groped her way down from the witness box.

The bailiff walked over to District Attorney Copeland, tapped him on the shoulder, and handed him a folded note.

Copeland studied the note with a puzzled expression, then said to Judge Meehan, “Your Honor, I think I have uncovered a very strange and unusual situation. If the Court will permit me, I would like to call a hostile witness.”

“Very well,” Judge Meehan said.

The district attorney got up, walked across the railed-off enclosure, and paused to stand looking at the black-garbed, heavily veiled figure of Mrs. Roland Burr, who was sitting in the front row of the spectators. He raised his voice and said dramatically, “If the Court please, I now wish to put on the stand Diana Burr, the widow of Roland Burr. She will be my next witness. Mrs. Burr, will you please come forward and be sworn?”

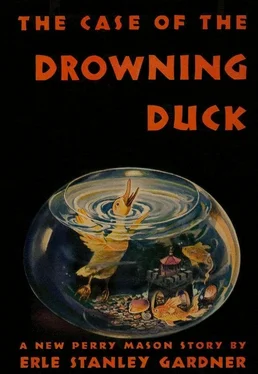

Mrs. Burr was surprised and indignant, but at Judge Meehan’s order to come forward, she walked to the witness stand, managing to look very tragic and dainty in her black mourning, and held up her hand and was sworn. She gave her name and address, then waited expectantly while District Attorney Copeland glanced around the courtroom to make certain that he had the undivided attention of the spectators. “Did you ever see a duck drown?” he asked dramatically.

This time there was no levity from the courtroom. It needed but a glance at Mrs. Burr’s countenance to make it plain that this was a moment filled with tense drama.

“Yes,” Mrs. Burr said, in a low voice.

In the silence which descended upon the courtroom, it was possible to hear the sounds of breathing and rustling garments as people moved uneasily in their chairs, straining to get a better view of the witness.

“Where?” District Attorney Copeland asked.

“At the home of John L. Witherspoon.”

“When?”

“About a week ago.”

“What happened?”

She said, “Marvin Adams talked about a drowning duck. My husband laughed at him, and Adams brought in a young duck and a fish bowl. He put something in the water, and the duck began to sink.”

Читать дальше