Copeland said, “Your Honor, I object. This is not proper cross-examination.”

“Why not?” Mason asked. “You’ve sought to connect the defendant with the murder of Milter.”

“But only for the purpose of showing familiarity with that particular method of perpetrating a murder,” the district attorney said.

“I don’t care what your purpose is or was,” Mason told him. “I’m going to prove that John L. Witherspoon couldn’t have had anything to do with the murder of Milter. I’m going to prove that Milter was dead before Witherspoon ever started up the stairs to that apartment. I m going to prove it by your own witnesses as well as by some of mine. And then I’m going to hurl your argument right back into your teeth. You’ve walked into this and...”

Judge Meehan pounded with his gavel. “Counsel will refrain from personalities,” he said. “Counsel will address his argument to the Court. ”

“Very well,” Mason said with a smile. “Your Honor, I submit that the district attorney has sought to introduce certain evidence for a limited purpose. There was no objection on the part of the defense to that evidence. He has shown the part of it which he thought would benefit his case. We’re entitled to show it all.”

“So far as this specific question is concerned,” Judge Meehan said, “the objection is overruled. The witness will answer it.”

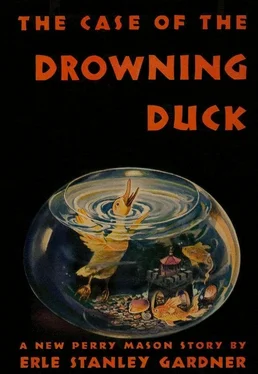

“That’s right. There was a duck in that goldfish bowl,” Haggerty said.

“And was there anything peculiar about that duck?”

“Yes”

“What?”

“Well, it seemed to be — it was sort of paddling around in the water — it looked like a duck that didn’t know how to swim — looked like it was drowning.”

The roar of laughter which came up from the courtroom drowned out the beating of the judge’s gavel.

Haggerty shifted his position uncomfortably on the stand, but glared dogged defiance at the laughing spectators.

“This being an agricultural community,” Mason conceded with a smile, when the uproar had subsided, “I take it that the idea of a duck that hasn’t learned how to swim, and drowns in a goldfish bowl is rather amusing to the spectators. Are you certain that the duck was drowning, Mr. Haggerty?”

Haggerty said, “There was something wrong with that duck. I don’t know what it was, but it was sunk down under the water. Just a little of it was sticking up.”

“Have you ever heard of ducks diving ?” Mason asked.

A titter ran around the courtroom.

Haggerty said, “Yes,” and then added, “But this was the first time I ever saw one dive stern first.”

A gale of laughter swept the courtroom before it was silenced.

“But you’re certain there was something wrong with the duck when you entered that room?” Mason asked, when order had been restored.

“Yes. It wasn’t sitting right. It was about two-thirds sunk.”

“What happened to the duck after that?” Mason asked.

“Well, the duck seemed to get well. I was pretty much all in myself from getting a whiff of that gas. Then, when I got to feeling better, I looked at the duck again. That time, it was floating on the water all right.”

“Was the duck still in the fish bowl when the defendant entered the apartment?” Mason asked.

“Yes.”

“Did the defendant make any statement about that duck?”

“Yes.”

“What?”

“He said it was his duck.”

“Anything else?”

“He said that Marvin Adams, a young man who had been calling at the house, had taken the duck away with him that evening.”

“And the defendant identified the duck positively?”

“Yes, absolutely. He said that he’d swear to it anywhere. It was his duck.”

Mason bowed and smiled. “Thank you very much, Officer Haggerty, for having made a very good witness. I have no further questions.”

District Attorney Copeland hesitated a moment, then called, “Alberta Cromwell.”

Alberta Cromwell marched down the aisle of the courtroom, held up her hand, took the oath, then seated herself in the witness chair. Once she glanced at Perry Mason, and her eyes were hard and defiant, the eyes of a woman who had made up her mind as to exactly what she is going to say, and has determined to deny those things she is not willing to admit.

Copeland was suave once more. This time he was on more familiar legal grounds, and his manner and the tone of his voice showed it. “Your name is Alberta Cromwell and you live here in El Templo?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And did so live on the night when this crime was alleged to have been committed?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You lived at eleven sixty-two Cinder Butte Avenue in an apartment house?”

“Yes, sir.”

“The same apartment house where the decedent, Leslie Milter lived?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And where was your apartment with reference to his?”

“My apartment was right next to his. There were two apartments on the second floor. He had one, and I had the other.”

“Was there any connecting door or any means of communication?”

“No, sir.”

“Now, on the night in question, did you see the defendant in this case, Mr. John L. Witherspoon?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Where and when?”

“It was about twenty minutes to twelve, perhaps a quarter of twelve. I can’t be certain of the exact time. I know that it was after eleven-thirty and before midnight.”

“ Where did you see him?”

“Just leaving the apartment of Leslie L. Milter.”

“Are you certain of your identification?”

“Yes, sir. I not only saw the man, but I took down the license number of his automobile. I am certain it was Mr. Witherspoon.”

“Now, do you know whether he left the apartment of the decedent, or...”

“Yes, sir,” she interrupted in her eagerness to answer the question. “I know that he left the apartment. I heard his feet coming down the stairs; then I heard the lower door open and slam, and he walked across the porch.”

“How could you see all this?”

“From my window. The house has two bay windows on each side of the second floor. One is on Mr. Milter’s side, and one is on my side. From my bay window, I could look down and see the door of Mr. Milter’s apartment.”

“You may cross-examine,” Copeland said.

Mason got slowly to his feet, his eyes boring steadily into those of the witness. “You were acquainted with Leslie Milter in his lifetime.”

“Yes.”

“You had known him in Los Angeles?”

Her eyes were defiant. “Yes.”

“You were his common-law wife?”

“No.”

“You were not his wife?”

“Absolutely not.”

“Did you ever claim to be his wife?”

“No.”

“Did you ever live with him as his wife?”

“Objected to as incompetent, irrelevant, and immaterial, not proper cross-examination,” Copeland roared, indignantly. “That question, if the Court please, is asked purely for the purpose of debasing the witness. It has absolutely no bearing on...”

“The objection is sustained.”

Mason bowed acknowledgement of the Court’s ruling, said respectfully, “Your Honor, if I might be permitted to argue the point, I think that the bias of a witness is a material factor and...”

“This Court is not going to permit the question,” Judge Meehan stated. “You are entitled to ask the witness if she was the wife of the decedent, if she had ever claimed to have been his wife. You are entitled to ask her if she was friendly with him, but having received the answers that you did, the Court rules that you are not entitled to place this witness in an embarrassing position in view of the present state of the record. You will understand, Counselor, that the evidence concerning the murder of Leslie Milter is introduced for a very limited purpose. While your right of cross-examination as to the facts which the officers encountered in that apartment is not limited, your cross-examination of this witness as to motivation is limited. The Court rules that the relationship called for in your question, even if it did ever exist, would be too remote.”

Читать дальше