“Wait, Lem. No use of all this. This young fellow looks like a good honest boy, even if his name is on Phil Escott’s door.” Having halted Sammis, he turned around. “So your name’s Tyler Dillon. I understand the sheriff and county attorney asked you some questions that had to do with Delia Brand and you refused to answer. That right?”

“It is.”

Anson nodded with a minimum of effort. “This morning Delia told me that she went to see you yesterday for legal advice. Naturally that made you her counsel.”

“That’s what I say, I’m her counsel.”

“Of course you are. But do you say that she specifically engaged you to defend her on this murder charge?”

“How could she?” Dillon was truculent. “There hadn’t been any murder—”

“Did she?”

“No.”

“Has anyone?”

“Not yet.”

Anson smiled the ghost of a smile. “Then it’s quite simple. There’s no occasion for any fuss. You’re not defending her on the murder charge and you’re not going to. I am. But you are her counsel, you know in what connection, I don’t.” He turned to confront the county attorney and his voice, though it remained scanty as to volume, was suddenly full of bite. “Ed, have you ever tried reading any law? And would you like to see a list of the Bar Association members of the committee that deals with infractions of ethics like trying to coerce information from a counselor regarding a privileged communication? And would you like to get Washington on long distance, as you did at twenty minutes past four this morning, and ask Carlson what job he has to suggest for you in case you happen to lose the one you’ve got now?”

Baker opened his mouth and shut it again.

Tyler Dillon demanded of the room and all in it, “I want to see Delia Brand! I have a right to see her!”

“Not now, my boy,” said Harvey Anson. “I’m sorry, but not just at present. Why don’t you drop in at my office this afternoon? Maybe we ought to have a little talk.”

Dillon looked around at the faces and saw it was hopeless. There was no one there susceptible to any appeal or pressure within his power. Sammis was still choleric, Phelan was impotent, Tuttle was hostile, Baker was speechless and Anson was impervious. There was nothing he could do. He wanted most of all to see her; he had a feeling that if only he could see her, for a brief moment even, he would then be able to think of things and do them — startling and efficient and conclusive things. He had gone about it wrong, he saw that now, but he must and would see her...

He turned on his heel and left the room.

Halfway down the gloomy basement corridor he heard quick light footsteps behind him and then was stopped by a hand on his arm.

It was Clara.

“I’m sorry, Ty,” she said, looking up at him. “I mean that I didn’t make good on what I said. But I didn’t know Mr. Sammis would be there and I just couldn’t. Anyway, it’s all right now, since they can’t question you about that paper.”

“I hope to heaven it is,” he said morosely. “But I’ve got to see her. I’ve got to find out... and what are they going to do? What are they doing? Someone has to do something!”

“They are. Surely they are.”

“I wish I thought so. I’m going to the office and see Escott and put it up to him. He’s friendly with Baker and maybe he can arrange for me to see her. Do you want to come along?”

“I guess I’ll go back home.”

They were outside in the shaded areaway and were about to emerge into the sunshine. Two men and a woman stood at the foot of the stone steps, talking. There was an exchange of glances, and the men and Dillon lifted their hats. The woman left them and approached. The electronic dispersion seemed to work as well outdoors as within walls; it competed successfully even with the sunshine.

“How do you do,” said Dillon as she got to them. “Have you met—”

“Sure,” Wynne Cowles said brusquely. She passed him up for Clara. “You poor thing. Lord, what a mess! I was out at the ranch and slept late and didn’t hear about it until eleven o’clock. I couldn’t get you on the phone, so I drove in, and you weren’t home so I came here. They told me you were inside and I’ve been waiting. You poor kid!” Her strange eyes probably made a display of compassion impractical, but it was in her voice. “What can I do?”

“Nothing,” said Clara. “There’s nothing you can do.”

“But there must be. I’ve never seen a situation yet where money couldn’t do something. And while I know you don’t want any charity, I would supply almost any amount, and call it a contribution to the public welfare, to keep that child from paying any price whatever for the removal of Dan Jackson.”

“She didn’t remove him. She didn’t do it.”

“No? Just as you say.” Wynne Cowles apparently allowed it as not worth arguing about. “But I mean it, Clara. Aren’t we partners? I’ll get a real lawyer from the coast, or the east, instead of one of these renovators — excuse it, Ty, my love, said only to offend — or I’ll buy a jury, I’ll buy the whole county which is nothing but volcano leavings anyhow, or I’ll round up a bunch of witnesses. I mean it. Anything.”

“Thanks, Mrs. Cowles, but—”

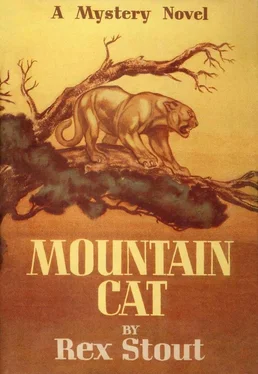

“Make it Wynne. We’re partners, aren’t we? Or M.C., that’s what they call me at the ranch. Short for Mountain Cat.”

“All right. But about being partners... I’m not sure—”

“Why not? You were yesterday.”

“Well — anyhow, it would have to wait.”

“Wait for what?”

“For this to be — my sister. I couldn’t discuss anything now — or start anything—”

“You’re a softie, Clara. It will do you good to be doing something. Don’t worry about your sister, we’ll take care of her. She’s a nice kid. Saw her yesterday. You ought to snap out of it; you look and talk as if someone had blackjacked you. Let’s go over to my suite at the Fowler and have a cocktail and some lunch and get your mind started working. Or out to the ranch — it only takes forty minutes—”

“I don’t want to go anywhere. Not today. I’m going home. Later I’m coming back here and see Delia.”

“Then I’ll go home with you. Let me go home with you?”

When they had settled for that, Dillon accompanied them to where Wynne Cowles’s long low convertible was parked before he headed for his office on Mountain Street. He hadn’t known that those two were acquainted and certainly not that they were partners.

At The Haven gambling parlors in the old Sammis Building on Halley Street, which, in a halfhearted sort of way, opened for business before noon, the awning was left down until the sun’s angle had passed beyond the perpendicular of the building line. Around three o’clock an employee in shirt sleeves emerged from the door with a crank in his hand. Before applying the crank and winding up the awning, he directed a look of appraisal at a man who stood near the door, in a niche between two stone pilasters. There was nothing extraordinary about the man — middle-aged, shoulders a little stooped — though he differed from the normal by having two strips of adhesive tape extending down his right cheekbone from under the brim of his hat, and by possessing a mustache of a quite unusual color, almost a fawn. The employee, having finished his task, glanced sharply at the man again and then disappeared inside.

In a few minutes the door opened again and the assistant manager of The Haven stepped out. With his habitual deadpan for a face, he went directly to the man in the niche and inquired, “You taking a census, brother?”

The man grunted and said, “I’m looking for a friend.”

Читать дальше