Ellery Queen

Cat of Many Tails

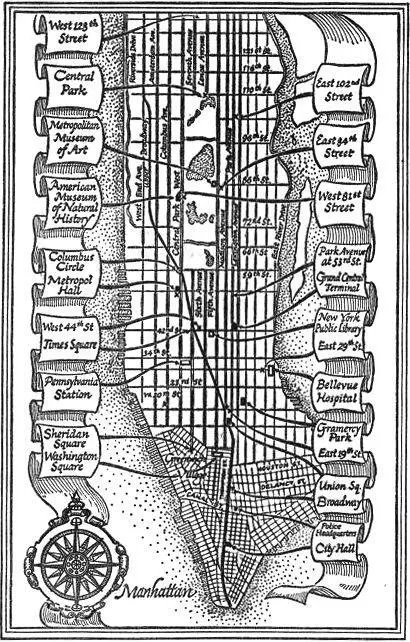

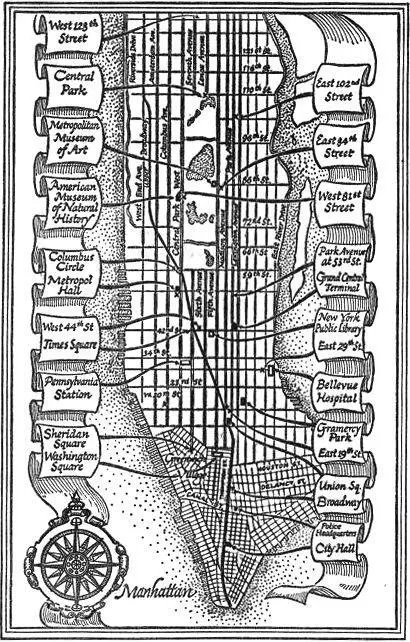

The strangling of Archibald Dudley Abernethy was the first scene in a nine-act tragedy whose locale was the City of New York.

Which misbehaved.

Seven and one-half persons inhabiting an area of over three hundred square miles lost their multiple heads all at once. The storm center of the phenomenon was Manhattan, that “Gotham” which, as the New York Times pointed out during the worst of it, had been inspired by a legendary English village whose inhabitants were noted for their foolishness. It was a not entirely happy allusion, for there was nothing jocular in the reality. The panic seizure caused far more fatalities than the Cat; there were numerous injured; and what traumata were suffered by the children of the City, infected by the bogey fears of their elders, will not be comprehended until the psychiatrists can pry into the neuroses of the next generation.

In the small area of agreement in which the scientists met afterward, several specific indictments were drawn. One charged the newspapers. Certainly the New York press cannot disclaim some responsibility for what happened. The defense that “we give John Public the news as it happens, how it happens, and for as long as it happens,” as the editor of the New York Extra put it, is plausible but fails to explain why John Public had to be given the news of the Cat’s activities in such necrotic detail, embellished by such a riches of cartoonical crape and obituary embroidery. The object of this elaborate treatment was, of course, to sell more newspapers — an object which succeeded so admirably that, as one circulation manager privately admitted, “We really panicked ’em.”

Radio was named codefendant. Those same networks which uttered approving sounds in the direction of every obsessionist who inveighed against radio mystery and crime programs as being the First Cause of hysteria, delinquency, seclusive behavior, idée fixe, sexual precocity, nailbiting, nightmare, enuresis, profanity, and other antisocial ills of juvenile America saw nothing wrong in thoroughly airing the depredations of the Cat, with sound effects... as if the sensational were rendered harmless by the mere fact of its being not fiction. It was later charged, not without justice, that a single five-minute newscast devoted to the latest horror of the strangler did more to shatter the nerves of the listening population than all the mystery programs of all the networks percussively put together. But by that time the mischief was done.

Others fished deeper. There were certain elements in the Cat’s crimes, they said, which plucked universal chords of horror. One was the means employed. Breath being life and its denial death, their argument ran, the pattern of strangulation was bound to arouse the most basic fears. Another was the haphazard choice of victims — “selection by caprice,” they termed it. Man, they stated, faces death most equably when he thinks he is to die for some purpose. But the Cat, they said, picked his victims at random. It reduced the living to the level of the sub-human and gave the individual’s extinction no more importance or dignity than the chance crushing of an ant. This made defenses, especially moral defenses, impossible; there was nowhere to hide; therefore panic. And still a third factor, they went on, was the total lack of recognition. No one lived who saw the terrorizer at his chill and motiveless work; he left no clues to his age, sex, height, weight, coloration, habits, speech, origin, even to his species. For all the data available, he might well have been a cat — or an incubus. Where nothing was to be perceived, the agitated imagination went berserk. The result was a Thing come true.

And the philosophers took the world view, opening casements to the great panorama of current events. Weltanschauung! they cried. The old oblate spheroid was wobbling on its axis, trying to resist stresses, cracking along faults of strain. A generation which had lived through two global conflicts; which had buried millions of the mangled, the starved, the tortured, the murdered; which rose to the bait of world peace through the bloody waters of the age and found itself, hooked by the cynical barb, of nationalism; which cowered under the inexplicable fungus of the atomic bomb, not understanding, not wishing to understand; which helplessly watched the strategists of diplomacy plot the tactics of an Armageddon that never came; which was hauled this way and that, solicited, exhorted, suspected, flattered, accused, driven, unseated, inflamed, abandoned, never at peace, never at rest, the object of pressures and contrary forces by the night and the day and the hour — the real victims of the universal War of Nerves... it was no wonder, the philosophers said, that such a generation should bolt screaming at the first squeak of the unknown. In a world that was desensitized, irresponsible, threatened and threatening, hysteria was not to be marveled at. It had attacked New York City; had it struck anywhere in the world, the people of that place would have given way. What had to be understood, they said, was that the people had welcomed panic, not surrendered to it. In a planet shaking to pieces underfoot it was too agonizing to remain sane. Fantasy was a refuge and a relief.

But it remained for an ordinary New Yorker, a 20-year-old law student, to state the case in language most people could understand. “I’ve just been reading up on Danny Webster,” he said. “In one case he was mixed up in, trial of a fellow named Joseph White, Webster tossed this one over the plate: Every unpunished murder takes away something from the security of every man’s life. I figure when you live in our cockeyed kind of world, when some boogyman they call the Cat starts sloughing folks right and left and nobody can get to first base on it, and as far as Joe Schmo can see this Cat’s going to keep right on strangling the population till there’s not enough customers left to fill the left field bleachers at Ebbets Field — or am I boring you and by the way whatever happened to Durocher?” The law student’s name was Gerald Ellis Kollodny and he made the statement to a Hearst reporter on sidewalk-interview assignment; the statement was reprinted in the New Yorker, the Saturday Review of Literature, and Reader’s Digest; M-G-M News invited Mr. Kollodny to repeat himself before its cameras; and New Yorkers nodded and said that was just about how it had stacked up.

August 25 brought one of those simmering subtropical nights in which summer New York specializes. Ellery was in his study stripped to his shorts, trying to write. But his fingers kept sliding off the keys and finally he turned off his desk light and padded to a window.

The City was blackly quiet, flattened by the pressures of the night. Eastward thousands would be drifting into Central Park to throw themselves to the steamy grass. To the northeast, in Harlem and the Bronx, Little Italy, Yorkville; to the southeast, on the Lower East Side and across the river in Queens and Brooklyn; to the south, in Chelsea, Greenwich Village, Chinatown — wherever there were tenements — fire escapes would be crowded nests in the smother, houses emptied, streets full of lackadaisical people. The parkways would be bug trails. Cars would swarm over the bridges — Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, Queensborough, George Washington, Triborough — hunting a breeze. At Coney Island, Brighton, Manhattan Beach, the Rockaways, Jones Beach, the sands would be seeded by millions of the sleepless turned restlessly to the sea. The excursion boats would be scuttling up and down the Hudson and the ferries staggering like overloaded old women to Weehawken and Staten Island.

Читать дальше