“Darned if I’m not growing romantic in my old age,” he growled. “The influence of a fiction-writing rascal of a son.”

He picked up the miscellaneous articles he himself had found on Tuesday in the pockets of the closet coats. Ellery was scowling now; Cronin was beginning to wear a forlorn, philosophical expression; the old man shuffled abstractedly among the keys, old letters, wallets, and then turned away.

“Nothing in the desk,” he announced wearily. “I doubt if that clever limb of Satan would have selected anything as obvious as a desk for a hiding place.”

“He would if he’d read Edgar Allen Poe,” murmured Ellery. “Let’s get on. Sure there is no secret drawer here?” he asked Cronin. The red head was shaken sadly but emphatically.

They probed and poked about in the furniture, under the carpets and lamps, in bookends, curtain rods. With each successive failure the apparent hopelessness of the search was reflected in their faces. When they had finished with the living room it looked as if it had innocently fallen in the path of a hurricane — a bare and comfortless satisfaction.

“Nothing left but the bedroom, kitchenette and lavatory,” said the Inspector to Cronin; and the three men went into the room which Mrs. Angela Russo had occupied Monday night.

Field’s bedroom was distinctly feminine in its accoutrements — a characteristic which Ellery ascribed to the influence of the charming Greenwich Villager. Again they scoured the premises, not an inch of space eluding their vigilant eyes and questing hands; and again there seemed nothing to do but admit failure. They took apart the bedding and examined the spring of the bed; they put it together again and attacked the clothes closet. Every suit was mauled and crushed by their insistent fingers — bathrobes, dressing gowns, shoes, cravats. Cronin halfheartedly repeated his examination of the walls and moldings. They lifted rugs and picked up chairs; shook out the pages of the telephone book in the bedside telephone table. The Inspector even lifted the metal disk which fitted around the steam-pipe at the floor, because it was loose and seemed to present possibilities.

From the bedroom they went into the kitchenette. It was so crowded with kitchen furnishings that they could barely move about. A large cabinet was rifled; Cronin’s exasperated fingers dipped angrily into the flour and sugar bins. The stove, the dish closet, the pan closet — even the single marble washtub in a corner — was methodically gone over. On the floor to one side stood the half empty case of liquor bottles. Cronin cast longing glances in this direction, only to look guiltily away as the Inspector glared at him.

“And now — the bathroom,” murmured Ellery. In an ominous silence they trooped into the tiled lavatory. Three minutes later they came out, still silently, and went into the living room where they disposed themselves in chairs. The Inspector drew out his snuffbox and took a vicious pinch; Cronin and Ellery lit cigarettes.

“I should say, my son,” said the Inspector in sepulchral tones after a painful interval broken only by the snores of the policeman in the foyer, “I should say that the deductive method which has brought fame and fortune to Mr. Sherlock Holmes and his legions has gone awry. Mind you, I’m not scolding...” But he slouched into the fastnesses of the chair.

Ellery stroked his smooth jaw with nervous fingers. “I seem to have made something of an ass of myself,” he confessed. “And yet those papers are here somewhere. Isn’t that a silly notion to have? But logic bears me out. When ten is the whole and two plus three plus four are discarded, only one is left... Pardon me for being old-fashioned. I insist the papers are here.”

Cronin grunted and expelled a huge mouthful of smoke.

“Your objection sustained,” murmured Ellery, leaning back. “Let’s go over the ground again. No, no!” he explained hastily, as Cronin’s face lengthened in dismay — “I mean orally... Mr. Field’s apartment consists of a foyer, a living room, a kitchenette, a bedroom and a lavatory. We have fruitlessly examined a foyer, a living room, a kitchenette, a bedroom and a lavatory. Euclid would regretfully force a conclusion here...” He mused, “How have we examined these rooms?” he asked suddenly. “We have gone over the obvious things, pulled the obvious things to pieces. Furniture, lamps, carpets — I repeat, the obvious things. And we have tapped floors, walls and moldings. It would seem that nothing has escaped the search...”

He stopped, his eyes brightening. The Inspector threw off his look of fatigue at once. From experience he was aware that Ellery rarely grew excited over inconsequential things.

“And yet,” said Ellery slowly, gazing in fascination at his father’s face, “by the Golden Roofs of Seneca, we’ve overlooked something — actually overlooked something!”

“What!” growled Cronin. “You’re kidding.”

“Oh, but I’m not,” chuckled Ellery, lounging to his feet “We have examined floors and we have examined walls, but have we examined — ceilings?”

He shot the word forth theatrically while the two men stared at him in amazement.

“Here, what are you driving at, Ellery?” asked his father, frowning.

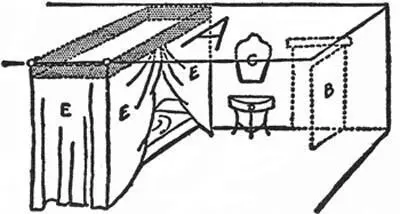

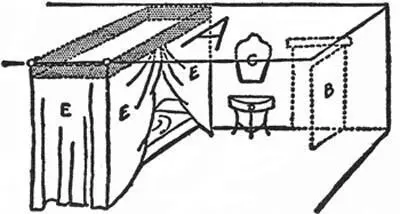

A — Ceiling

B — Door to Living Room

C — Mirror

D — Dressing Table

E — Damask curtains around bed, from ceiling to floor, concealing Shaded portino which represents panel containing hats.

Ellery briskly crushed his cigarette in an ashtray. “Just this,” he said. “Pure reasoning has it that when you have exhausted every possibility but one in a given equation that one, no matter how impossible, no matter how ridiculous it may seem in the postulation — must be the correct one... A theorem analogous to the one by which I concluded that the papers were in this apartment.”

“But, Mr. Queen, for the love of Pete — ceilings!” exploded Cronin, while the Inspector looked guiltily at the living room ceiling. Ellery caught the look and laughed, shaking his head.

“I’m not suggesting that we call in a plasterer to maul these lovely middle-class ceilings,” he said. “Because I have the answer already. What is it in these rooms somewhere that is on the ceiling?”

“The chandeliers,” muttered Cronin doubtfully, gazing upward at the heavily bronzed fixture above their heads.

“By jinks — the canopy over the bed!” shouted the Inspector. He jumped to his feet and ran into the bedroom. Cronin pounded hard after him, Ellery sauntering interestedly behind.

They stopped at the foot of the bed and stared up at the canopy. Unlike the conventional canopies of American style, this florid ornament was not merely a large square of cloth erected on four posts, an integral part of the bed only. The bed was so constructed that the four posts, beginning at the four corners, stretched from floor to ceiling. The heavy maroon-colored damask of the canopy also reached from floor to ceiling, connected at the top by a ringed rod from which the folds of the damask hung gracefully.

“Well, if it’s anywhere,” grunted the Inspector, dragging one of the damask-covered bedroom chairs to the bed, “it’s up here. Here, boys, lend a hand.”

He stood on the chair with a fine disregard for the havoc his shoes were wreaking on the silken material. Finding upon stretching his arms above his head that he was still many feet short of touching the ceiling, he stepped down.

“Doesn’t look as if you could make it either, Ellery,” he muttered. “And Field was no taller than you. There must be a ladder handy somewhere by which Field himself got up here!”

Читать дальше