Ellery Queen

The Greek Coffin Mystery

To

M. B. W.

WITH GRATITUDE

GEORG KHALKIS art dealer

GILBERT SLOANE manager, Khalkis Galleries

DELPHINA SLOANE Khalkis’ sister

ALAN CHENEY son of Delphina Sloane

DEMMY Khalkis’ cousin

JOAN BRETT Khalkis’ secretary

JAN VREELAND Khalkis’ traveling representative

LUCY VREELAND Vreeland’s wife

NACIO SUIZA director of Khalkis’ art-gallery

ALBERT GRIMSHAW ex-convict

DR. WARDES English eye-specialist

MILES WOODRUFF Khalkis’ attorney

JAMES J. KNOX millionaire art-connoisseur

DR. DUNCAN FROST Khalkis’ personal physician

MRS. SUSAN MORSE a neighbor

JEREMIAH ODELL plumbing contractor

LILY ODELL Odell’s wife

REV. JOHN HENRY ELDER SEXTON

HONEYWELL WEEKES Khalkis’ butler

MRS. SIMMS Khalkis’ housekeeper

PEPPER Assistant District Attorney

SAMPSON District Attorney

COHALAN D. A. detective

DR. SAMUEL PROUTY Assistant Medical Examiner

EDMUND CREWE architectural expert

UNA LAMBERT handwriting expert

“JIMMY” fingerprint expert

TRIKKALA Greek interpreter

FLINT, HESSE, JOHNSON, PIGGOTT, HAGSTROM, RITTER staff detectives

THOMAS VELIE detective sergeant

DJUNA

INSPECTOR RICHARD QUEEN

ELLERY QUEEN

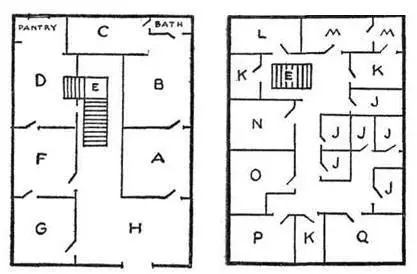

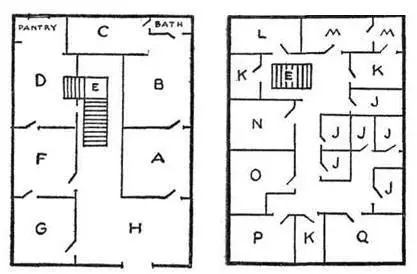

FLOOR PLAN OF KHALKIS HOUSE

A — Khalkis’ library

B — Khalkis’ bedroom

C — Demmy’s bedroom

D — kitchen

E — stairs to 2nd floor

F — dining room

G — drawing room

H — foyer

J — servants’ rooms

K — bathrooms

L — Vreelands’ room

M — Sloanes’ rooms

N — Joan Brett’s room

O — Dr. Wardes’ room

P — Cheney’s room

Q — second guest room

Attic not divided into rooms

“IN SCIENCE, IN HISTORY, in psychology, in all manner of pursuits which require an application of thought to the appearance of phenomena, things are very often not what they seem. Lowell, the illustrious American thinker, said: ‘A wise scepticism is the first attribute of a good critic.’ I think precisely the same theorem can be laid down for the student of criminology...

“The human mind is a fearful and tortuous thing. When any part of it is warped — even if it be so lightly that all the instruments of modern psychiatry cannot detect the warping — the result is apt to be confounding. Who can describe a motive? A passion? A mental process?

“My advice, the gruff dictum of one who has been dipping his hands into the unpredictable vapours of the brain for more years than he cares to recall, is this: Use your eyes, use the little grey cells God has given you, but be ever wary. There is pattern but no logic in criminality. It is your task to cohere confusion, to bring order out of chaos.”

— Closing Address by PROF. FLORENZ BACHMANN to Class in

Applied Criminology at University of Munich (1920)

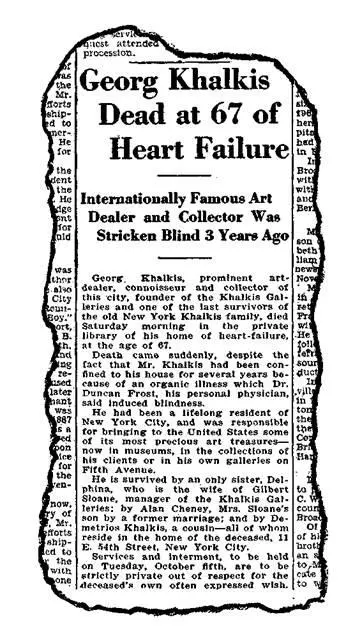

From the very beginning the Khalkis case struck a somber note. It began, as was peculiarly harmonious in the light of what was to come, with the death of an old man. The death of this old man wove its way, like a contrapuntal melody, through all the intricate measures of the death march that followed, in which the mournful strain of innocent mortality was conspicuously absent. In the end it swelled into a crescendo of orchestral guilt, a macabre dirge whose echoes rang in the ears of New York long after the last evil note had died away.

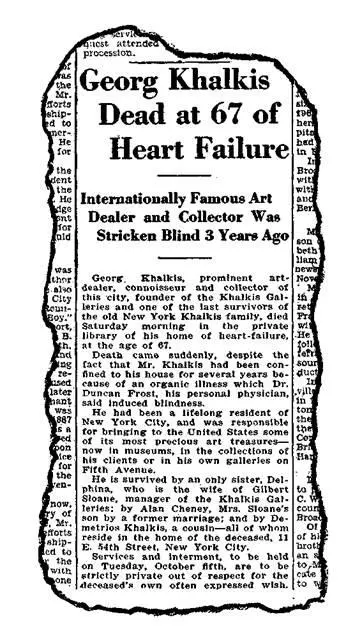

It goes without saying that when Georg Khalkis died of heart failure no one, least of all Ellery Queen, suspected that this was the opening motif in a symphony of murder. Indeed, it is to be doubted that Ellery Queen even knew that Georg Khalkis had died until the fact was forcibly brought to his attention three days after the blind old man’s clay had been consigned, in a most proper manner, to what every one had reason to believe was its last resting-place.

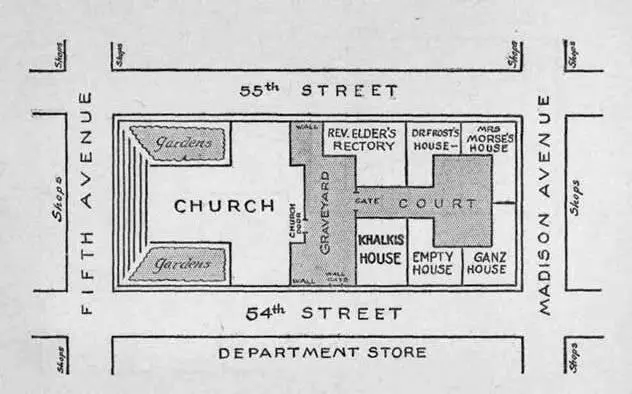

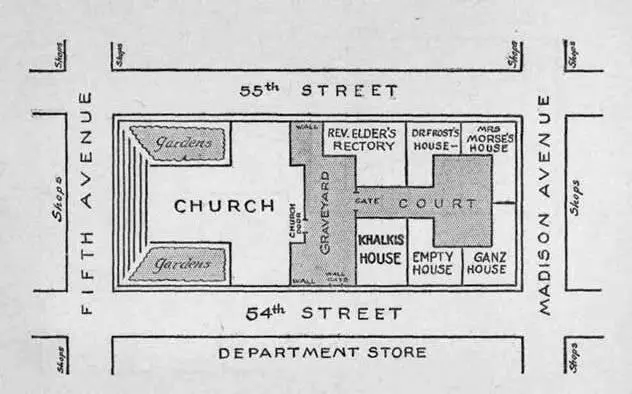

What the newspapers failed to make capital of in the first announcement of Khalkis’ death — an obituary tribute which Ellery, a violent non-reader of the public prints, did not catch — was the interesting location of the man’s grave. It gave a curious sidelight on old New Yorkana. Khalkis’ drooping brownstone at 11 East Fifty-fourth Street was situated next to the tradition-mellowed church which fronts Fifth Avenue and consumes half the area of the block between Fifth and Madison Avenues, flanked on the north by Fifty-fifth Street and on the south by Fifty-fourth Street. Between the Khalkis house and the church itself was the church graveyard, one of the oldest private cemeteries in the city. It was in this graveyard that the bones of the dead man were to be interred. The Khalkis family, for almost two hundred years parishioners of this church, were not affected by that article of the Sanitary Code which forbids burial in the heart of the city. Their right to lie in the shadow of Fifth Avenue’s skyscrapers was established by their traditional ownership of one of the subterranean vaults in the church graveyard — vaults not visible to passersby, since their adits were sunken three feet below the surface, leaving the sod of the graveyard unmarred by tombstones.

The funeral was quiet, tearless and private. The dead man, embalmed and rigged out in evening clothes, was laid in a large black lustrous coffin, resting on a bier in the drawing-room on the first floor of the Khalkis house. Services were conducted by the Reverend John Henry Elder, pastor of the adjoining church — that Reverend Elder, it should be noted, whose sermons and practical diatribes were given respectful space in the metropolitan press. There was no excitement, and except for a characteristic swooning entered upon with vigor by Mrs. Simms, the dead man’s Housekeeper, no hysteria.

Yet, as Joan Brett later remarked, there was something wrong. Something that may be attributed, we may suspect, to that superior quality of feminine intuition which, medical men are prone to say, is sheer nonsense. Nevertheless she described it, in her straight-browed and whimsical English fashion, as “a tightness in the air.” Who caused the tightness, what individual or individuals were responsible for the tension — if indeed it existed — she could not or would not say. Everything, on the contrary, seemed to go off smoothly and with just the proper touch of intimate, unexploited grief. When the simple services were concluded, for example, the members of the family and the scattering of friends and employees present filed past the coffin, took their last farewell of the dead clay, and returned decorously to their places. Faded Delphina wept, but she wept in the aristocratic manner — a tear, a dab, a sigh. Demetrios, whom no one would dream of addressing by any other name than Demmy, stared his vacant idiot’s stare and seemed fascinated by his cousin’s cold placid face in the coffin. Gilbert Sloane patted his wife’s pudgy hand. Alan Cheney, his face a little flushed, had jammed his hands into the pockets of his jacket and was scowling at empty air. Nacio Suiza, director of the Khalkis art-gallery, correct to the last detail of funereal attire, stood very languidly in a corner. Woodruff, the dead man’s attorney, honked his nose. It was all very natural and innocuous. Then the undertaker, a worried-looking, bankerish sort of man by the name of Sturgess, manipulated his puppets and the coffin-lid was quickly fastened down. Nothing remained but the sordid business of organizing the last procession. Alan, Demmy, Sloane and Suiza took their places by the bier, and after the customary confusion had subsided, hoisted the coffin to their shoulders, passed the critical scrutiny of Undertaker Sturgess, the Reverend Elder murmured a prayer, and the cortège walked firmly out of the house.

Читать дальше