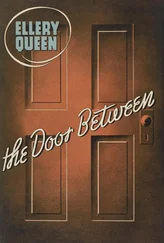

The three men hastened out of the office, to the astonishment of Mrs. Shane, and darted down the corridor. They turned the corner and ran to the left, stopping at the first door across the hall from the Kirk suite, the door Miss Diversey had used more than an hour earlier.

Ellery grasped the knob and turned. It moved, and he pushed; the door was unlocked. It swung inward slowly.

Ellery stood still, impaled by shock. Over his shoulder the faces of Donald Kirk and James Osborne worked spasmodically.

Then Kirk said in a flat shrinking voice: “Good God, Queen.”

The room looked as if some giant hand had plucked it bodily from the building, shaken it like a dice-cup, and flung it back. At first glance it seemed in a state of utter confusion. All the furniture had been moved. There was something wrong with the pictures on the wall. The rug looked odd. The chairs, the table, everything...

The goggling human eyes could not encompass more than a certain degree of destruction in one transfixed glimpse. There was primarily an impression of ruthless havoc, of furious dismantlement. But the impression was ephemeral; it could not withstand the single dreadful reality.

Their eyes were dragged to something lying across the room on the floor before the bolted door leading to the office. It was the stiff body of the stout middle-aged man, his bald skull no longer pink but white spattered with carmine, streaks of caked jelly radiating from a blackish depression at the top. He was lying face down, his short fat arms crumpled under him. Two unbelievable iron things, like horns, stuck out from under his coat at the back of his neck.

“Dead?” whispered Kirk.

Ellery stirred. “Well, what do you think?” he said harshly and took a forward step. Then he stopped, and his eyes flashed from one incredible part of the room to another as if they could not believe what they saw.

“Why, it’s murder,” said Osborne in a queer interrogatory voice. Ellery could hear the man swallowing rapidly and unconsciously behind him.

“A man doesn’t wallop himself over the head with a poker, Osborne,” said Ellery, unmoving. They all looked at it without expression; a heavy brass poker, apparently from the rack of firetools before the ornamental fireplace, lay on the rug a few feet from the body. It was daubed with the same red jelly that smeared the stout little man’s skull.

Then Ellery stepped forward, walking lightly as if he were afraid to disturb even the molecules of the air in the room. He knelt by the prone figure. There was so much to see, so much more to assimilate mentally... He shut his eyes to the astounding condition of the still little man’s clothes and felt beneath the body for the heart. No quiver of arterial life responded to his fingertips. He withdrew his own chilled hand and touched the skin of the man’s bland pale face. It was cold with the unearthly cold of death.

There was a suspicion of purple on the face... Ellery touched the dead chin with his fingers and tilted the head. Yes, there was a purplish patch of bruise on the left cheek and the left side of the nose and mouth. He had fallen like a stone to receive the hard kiss of the floor on that side of his face.

Ellery rose and silently retreated to his former position inside the doorway. “It’s a question of perspective,” he said to himself, never taking his eyes from the dead man. “You can’t see much close up. I wonder—” A fresh surge of astonishment flooded his brain. In all the years that he had seen dead men in the fixed surroundings of violence he had never witnessed anything so remarkable as this dead man and the things that had been done to him and to his last resting-place. There was something uncanny about the whole thing, uncanny and horrifying. The sane mind shrank from acceptance. It was unholy, blasphemous...

How long they stood there, the three of them, none of them knew. The corridor at their backs was very quiet. Only occasionally they heard the clang of the elevator-door and the cheerful voice of Mrs. Shane. From the street twenty-two stories below came the whispering sounds of traffic, wafted past the blowing curtains of one of the windows. For a weird moment the thought struck them simultaneously that the little man was not dead but merely taking a humorous rest on the floor, having selected his odd position and the extraordinary disruption of his surroundings out of some inscrutable whim. The thought was born of the benevolent smile on the dead man’s fat lips, for his face was turned toward them. Then the impression faded, and Ellery cleared his throat noisily, as if to grasp something real, if only a sound.

“Kirk, have you ever seen this fellow before?”

The tall young man’s breath whistled through his nostrils behind Ellery’s back. “Queen, I swear I’ve never seen him before. You’ve got to believe me!” He clutched Ellery’s arm with a muscular convulsiveness. “Queen! It’s a ghastly mistake, I tell you. Strangers are always coming to see me. I never saw—”

“Tch,” murmured Ellery, “get a stranglehold on your nerve’s, Kirk.” Without turning he patted Kirk’s rigid fingers. “Osborne.”

Osborne said with difficulty: “I can vouch for that, Mr. Queen. He’s never been here before. He was a total stranger to us. Mr. Kirk doesn’t know—”

“Yes, yes, Osborne. With all the other appalling things about this crime, I can well believe...” He tore his eyes from the prone figure and swung about, a businesslike note springing into his voice, “Osborne, go back to your office and ’phone down for the physician, the manager, and the house detective. Then call the police. Get Centre Street; speak to Inspector Richard Queen. Tell him I’m on the scene and to hurry over at once.”

“Yes, sir,” quavered Osborne, and slipped away.

“Now, close that door, Kirk. We don’t want any one to see—”

“Don,” said a girlish voice from the corridor. Both men swung about instantly, blocking her line of vision. She was staring in at them — a girl as tall as Kirk, with a slender immature figure and great hazel eyes. “Don, what’s the trouble? I saw Ozzie running... What’s in there? What’s happened?”

Kirk said in a quick hoarse voice: “Nothing, nothing at all, ’Cella,” and jumped out into the hall and placed his hands on his sister’s half-bare shoulders. “Just an accident. Go back to the apartment—”

Then she saw the dead man lying on the floor in the anteroom. The color washed out of her face and her eyes rolled over like a dying doe’s. She screamed once, piercingly, and tumbled to the floor as limply as a rag-doll.

At once, as if her scream had been a signal, bedlam howled about them. Doors across the corridor flew open and spewed forth people with glaring eyes and moving mouths. Miss Diversey, her cap askew, came padding down the hall. Behind her rolled the tall, hollow-boned, emaciated figure of Dr. Hugh Kirk, his wheelchair trundling swiftly; he was collarless and coatless, and his stiff-bosomed shirt lay open above his gray-haired chest. The tiny black-gowned woman, Miss Temple, came flying out of nowhere to drop on her knees beside the unconscious girl. Mrs. Shane puffed around the corner screeching questions. A bellboy sped past her, looking about wildly. A small bony British-looking man in butler’s panoply stared pasty-faced out of one of the Kirk doors as the others milled about the fallen girl, blundering into one another.

In the confusion Ellery, who had not stirred from the doorway, sighed and retreated, closing the door of the anteroom behind him. The sounds became live echoes. He stood guard with his back to the door, just looking at the dead man and the furniture and back at the dead man again. He made no move to touch anything.

Читать дальше