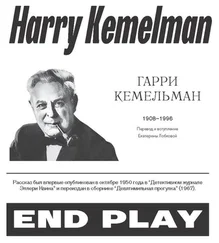

Гарри Кемельман - Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Гарри Кемельман - Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The fifth in a series of definitive editions of Rabbi David Small mysteries by award-winning author Harry Kemelman!

Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Sure. Let me get my shoes on and I'll run you down to the station. You can talk to him in my office if you'd like."

The young man was visibly surprised when he saw the rabbi. "Oh, it's you,” he said. "I thought it was the lawyer guy again." He walked the length of the room and looked out the window, then he faced around. "Cops!" he exclaimed. "They're not human. Do you think he'd bother to tell me who's here? He just says somebody wants to see me in the chiefs office, and when I tell him I don't care to go— thinking it was the lawyer or my old man— he says, 'On your feet, bigshot,’ and practically hauls me up here."

"He probably didn't know who it was either," the rabbi said mildly.

"Rabbi, you don't know these guys. You just haven't had the experience."

"All right," he said good-naturedly. "Now what's your objection to cooperating with the lawyer?"

Abner Selzer spread his hands and let his shoulders droop in exasperation. "Goodman! He didn't ask me a thing, he just said if I was planning on making a speech, forget it. I'd be standing before Judge Visconte and he's hard as nails, he'd throw the book at me. If the judge asks a question, he says. I'm supposed to stand up and address him as Your Honor. Otherwise, keep quiet, don't whisper with the others. Just sit up straight, look straight ahead at the judge, and look interested, that's planning a defense? Then he takes a look at me and tells me he wants me clean- shaven and wearing a regular suit when I come to court tomorrow morning. Rabbi, how can I communicate with a man like that? So I asked him how would it be if I wore a kilt and crossed my legs and showed part of my behind to the jury."

The rabbi laughed and the young man grinned. "What did he say to that?"

"He got sore and just said he'd see me in the court in Boston."

"I don't suppose it makes much difference." said the rabbi. "The arraignment is largely a formality, as I understand it, the law requires you to be brought before a magistrate within twenty-four hours of your arrest."

"But what if a guy's innocent?"

"That's not the judge's concern at an arraignment, Abner, he's there just to determine whether the police have enough evidence to hold you for the grand jury. If they want you held, the judge will usually go along, all right, I can understand about your lawyer, but why don't you want to see your father?"

"So he can yell at me? We can't talk for five minutes before he starts yelling."

"What does he yell about?" asked the rabbi curiously.

"Oh, almost anything, but mostly— until now, at least— about marks. 'Shape up.' he's always saying. Why don't I shape up, or sometimes. 'Shape up or ship out.' He was in the naval reserve for a while, that's where he got it. When I was in high school here, it wasn't so bad. I was one of the smart kids, and besides the other kids' fathers did the same thing. But at Harvard. I was up against all the other smart kids, and I wasn't living at home where he could keep tabs on me every night— C or even B-minus wasn't good enough for him. It had to be A's, and for a while. I tried, but the competition was tough and I thought, the hell with it."

"So you slacked off completely."

"Sure, why not? I was working so hard and got a B-minus, but it wasn't good enough for him. So I thought it won't be any worse if I have a little fun and get a C or even a C-minus."

"But you felt guilty about it."

The young man considered. "All right. I suppose I did— at first. I don't now."

"Are you sure?"

"Yeah, I'm sure. I'll tell you something. Rabbi. My father didn't care if I learned anything or not, he was just interested in my getting good marks so I could get into a good law school and get good marks there, even if I never learned any law, so I could get into a big law firm."

"I suppose he's trying to fit you for the world as he sees it."

"So what's wrong with trying to change it?" demanded Selzer."Well, you might change it for the worse." the rabbi observed wryly. "But in any case, by your own admission, whatever your father is doing, whether he's going about it the right way or not, he's doing it for you."

"Rabbi." said Abner solemnly, "this is going to shock you, but the fact is I don't care very much for my father. I don't respect him and—"But it was Abner who was shocked when the rabbi interrupted to say, "Oh, that's perfectly normal."

"It is?"

"I would say so, that's why it's one of the ten commandments. 'Honor thy father and mother.’ If it were perfectly natural, it wouldn't require a specific commandment, would it?"

"All right, so why should I accept help from somebody I don't respect?"

"Because it's childish and peevish to refuse help when you are in need." said the rabbi. "You're going to have a lawyer whether you want one or not. If you don't use your own, the court will appoint one for you, he may be better than Mr. Goodman, but it's not likely, and he's certain to be less experienced. Common sense would suggest that you get the best you can."

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

Judge Visconte's head nodded slightly as he read the complaint. When he put the paper aside, his head continued to nod, for he was an old man, well over seventy, with snow-white hair surrounding a high, slanting forehead. His handsome Italian face with its long Roman nose looked benign and grandfatherly.

He turned to Bradford Ames. "The Commonwealth has a recommendation on bail?"

"The Commonwealth has a recommendation. Your Honor." said Ames. "It is the Commonwealth's opinion that since a man was killed as a direct result of the explosion of a bomb, this is a case of felony murder and hence that bail should be denied."

The judge nodded vigorously in apparent agreement, then he inclined his head and nodded at a somewhat different angle, which the clerk interpreted as a sign that His Honor wanted to confer with him, he leaned over the judge's desk and they whispered together. It looked as though it was all over.

Paul Goodman rose beside the attorney's table. "May I be heard, Your Honor?"

The judge nodded graciously.

"To save the time of the Honorable Court, I am speaking not only for myself but for my three colleagues who are each representing one of these young defendants. It seems to me. Your Honor, that the recommendation of the Commonwealth is punitive rather than designed to insure the appearance of the defendants at their trial, these young people are not professional criminals; they have clean records, they are enrolled in college; if they are prevented from attending classes they will be unable to pass their courses. To hold them in jail pending their trial is to punish them before they have been proven guilty."

The judge nodded benevolently. "It's always punitive, isn't it?" he said gently. "A workman loses his wages; a businessman sometimes has to close down his business or office, and in every case, the family suffers."

"If I may, Your Honor." said Goodman. "Isn't that all the more reason not to hold these young people unnecessarily, since the danger of their not appearing for the trial is slight?"

"But the charge is murder. Counselor."

"I recognize that it has been the prevailing practice in the Commonwealth to deny bail to prisoners charged with murder. But my understanding is that the rationale—"

"Did you say rationale?"

"Yes. Your Honor. I was saying that the rationale behind denying bail in such cases is that money becomes secondary when a man's life is at stake. However, since the Supreme Court of the United States has held the death penalty to be cruel and unusual punishment, that fear no longer obtains."

"On the other hand," the judge interposed, "these young people— and I have had a lot of experience with them; oh yes— are apt to be rather cavalier about money. If I were to set bail, even very high bail, which their parents might arrange to meet, there is a strong possibility— and I speak from experience— that they may fail to appear, having no regard for the loss which their parents would thus incur. No, Counselor, I think I'll go along with the Commonwealth recommendation and order them held without bail."

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tuesday The Rabbi Saw Red» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.