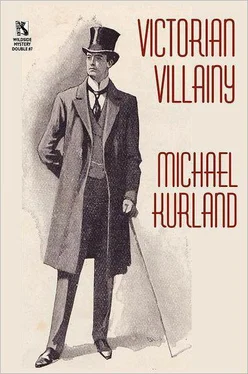

Michael Kurland - Victorian Villainy

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Michael Kurland - Victorian Villainy» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Victorian Villainy

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Victorian Villainy: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Victorian Villainy»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Victorian Villainy — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Victorian Villainy», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Again note that after a six-month absence, during which Holmes and I-but no, it is not my secret to tell-at any rate, six months after I was assumed to be dead I returned to my home on Russell Square and went about my business as usual, and Watson affected not to notice. After all, Holmes had killed me, and that was good enough for Watson.

I could go on. Indeed, it is with remarkable restraint that I do not. To describe me as a master criminal is actionable; and then to compound matters by making me out to be such a bungler as to be fooled by Holmes’s juvenile antics is quite intolerable. It should be clear to all that the events leading up to that day at Reichenbach Falls, if they occurred as described, were designed by Holmes to fool his amiable companion, and not “the Napoleon of crime.”

But I have digressed enough. In this brief paper I will describe how the relationship between Holmes and myself came to be, and perhaps supply some insight into how and why Holmes developed an entirely unwarranted antagonism toward me that has lasted these many years.

I first met Sherlock Holmes in the early 1870s-I shall be no more precise than that. At the time I was a senior lecturer in mathematics at, I shall call it, “Queens College,” one of the six venerable colleges making up a small inland university which I shall call “Wexleigh” to preserve the anonymity of the events I am about to describe. I shall also alter the names of the persons who figure in this episode, save only those of Holmes and myself; as those who were involved surely have no desire to be reminded of the episode or pestered by the press for more details. You may, of course, apply to Holmes for the true names of these people, although I imagine that he will be no more forthcoming than I.

Let me also point out that memories are not entirely reliable recorders of events. Over time they convolute, they conflate, they manufacture, and they discard, until what remains may bear only a passing resemblance to the original event. So if you happen to be one of the people whose lives crossed those of Holmes and myself at “Queens” at this time, and your memory of some of the details of these events differs from mine, I assure you that in all probability we are both wrong.

Wexleigh University was of respectable antiquity, with respectable ecclesiastical underpinnings. Most of the dons at Queens were churchmen of one description or another. Latin and Greek were still considered the foundations upon which an education should be constructed. The “modern” side of the university had come into existence a mere decade before, and the Classics dons still looked with mixed amazement and scorn at the Science instructors and the courses offered, which they insisted on describing as “Stinks and Bangs.”

Holmes was an underclassman at the time. His presence had provoked a certain amount of interest among the faculty, many of whom remembered his brother Mycroft, who had attended the university some six years previously. Mycroft had spent most of his three years at Queens in his room, coming out only for meals and to gather armsful of books from the library and retreat back to his room. When he did appear in the lecture hall it would often be to correct the instructor on some error of fact or pedagogy that had lain unnoticed, sometimes for years, in one of his lectures. Mycroft had departed the university without completing the requirements for a degree, stating with some justification that he had received all the institution had to offer, and he saw no point in remaining.

Holmes had few friends among his fellow underclassmen and seemed to prefer it that way. His interests were varied but transient, as he dipped first into one field of study and then another, trying to find something that stimulated him sufficiently for him to make it his life’s work; something to which he could apply his powerful intellect and his capacity for close and accurate observation, which was even then apparent, if not fully developed.

An odd sort of amity soon grew between myself and this intense young man. On looking back I would describe it as a cerebral bond, based mostly on the shared snobbery of the highly intelligent against those whom they deem as their intellectual inferiors. I confess to that weakness in my youth, and my only defense against a charge of hubris is that those whom we went out of our way to ignore were just as anxious to avoid us.

The incident I am about to relate occurred in the Fall, shortly after Holmes returned to begin his second year. A new don joined the college, occupying the newly-created chair of Moral Philosophy, a chair which had been endowed by a midlands mill owner who made it a practice to employ as many children under twelve in his mills as his agents could sweep up off the streets. Thus, I suppose, his interest in Moral Philosophy.

The new man’s name was-well, for the purposes of this tale let us call him Professor Charles Maples. He was, I would judge, in his mid forties; a stout, sharp-nosed, myopic, amiable man who strutted and bobbed slightly when he walked. His voice was high and intense, and his mannerisms were complex. His speech was accompanied by elaborate hand motions, as though he would mold the air into a semblance of what he was describing. When one saw him crossing the quad in the distance, with his grey master of arts gown flapping about him, waving the mahogany walking-stick with the brass duck’s-head handle that he was never without, and gesticulating to the empty air, he resembled nothing so much as a corpulent king pigeon.

Moral Philosophy was a fit subject for Maples. No one could say exactly what it encompassed, and so he was free to speak on whatever caught his interest at the moment. And his interests seemed to be of the moment: he took intellectual nourishment from whatever flower of knowledge seemed brightest to him in the morning, and had tired of it ere night drew nigh. Excuse the vaguely poetic turn of phrase; speaking of Maples seems to bring that out in one.

I do not mean to suggest the Maples was intellectually inferior; far from it. He had a piercing intellect, an incisive clarity of expression, and a sarcastic wit that occasionally broke through his mild facade. Maples spoke on the Greek and Roman concept of manliness, and made one regret that we lived in these decadent times. He lectured on the nineteenth-century penchant for substituting a surface prudery for morality, and left his students with a vivid image of unnamed immorality seething and billowing not very far beneath the surface. He spoke on this and that and created in his students with an abiding enthusiasm for this, and an unremitting loathing for that.

There was still an unspoken presumption about the college that celibacy was the proper model for the students, and so only the unmarried, and presumably celibate, dons were lodged in one or another of the various buildings within the college walls. Those few with wives found housing around town where they could, preferably a respectable distance from the university. Maples was numbered among the domestic ones, and he and his wife Andrea had taken a house with fairly extensive grounds on Barleymore Road not far from the college, which they shared with Andrea’s sister Lucinda Moys and a physical education instructor named Crisboy, who, choosing to live away from the college for reasons of his own, rented a pair of rooms on the top floor. There was a small guest house at the far end of the property which was untenanted. The owner of the property, who had moved to Glasgow some years previously, kept it for his own used on his occasional visits to town. The Maples employed a cook and a maid, both of whom were day help, sleeping in their own homes at night.

Andrea was a fine-looking woman who appeared to be fearlessly approaching thirty, with intelligent brown eyes set in a broad face and a head of thick, brown hair, which fell down her back to somewhere below her waist when she didn’t have it tied up in a sort of oversized bun circling her head. She was of a solid appearance and decisive character.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Victorian Villainy»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Victorian Villainy» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Victorian Villainy» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Brian Thompson - A Monkey Among Crocodiles - The Life, Loves and Lawsuits of Mrs Georgina Weldon – a disastrous Victorian [Text only]](/books/704922/brian-thompson-a-monkey-among-crocodiles-the-life-thumb.webp)