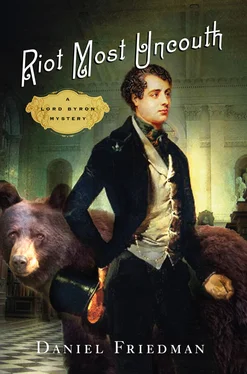

Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Riot Most Uncouth

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9781250027580

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Riot Most Uncouth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Riot Most Uncouth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Riot Most Uncouth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Riot Most Uncouth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

My father, too, had grown unkempt and wild in those last dire weeks. His beard was shaggy and mottled with patches of white, though he had yet to reach his thirty-fifth year. His hair was lank and dirty, and his clothing was tattered and stained. He had not been sober in days.

“Mother believes I can get better,” I said. “I am going to see a doctor.”

I’d been to lots of doctors, in fact. As my father’s health and the family finances deteriorated, my mother had become increasingly preoccupied with fixing my clubfoot. The treatments hurt. The braces the doctors screwed onto my leg caused constant pain. But I tried not to cry; I wanted to be better, to be worthy in my father’s estimation. I wanted to be a soldier one day, to follow in Mad Jack’s path; to thrive in the family business of war-making.

“The doctor is a charlatan,” he said. “Your mother is stupid, and so are you. Nothing can fix you; you’re a physical manifestation of my failings and inadequacies, a curse from God. He wants me to stare at your misshapen form every day as punishment for my sins.”

My mother, overhearing this, swept me up and lifted me away from him with her plump round arms. “Why are you so cruel to him, Jack? He’s only a child.”

“His flesh isn’t worth the price of what I feed him. If I could swap him for a cask of low-end whisky, I would. But nobody wants a defective child, not even the vrykolakas. He’s thick and stupid, like you, Catherine, and so is his damned gimpy blood. He would offend the tastes of even the most ravenous ghoul.”

Just then, four men carried a heavy armoire out of the house to load it on the back of a cart drawn by two big draft horses. Mad Jack winged a plate at them but missed. One of the men swore loudly, but my father ignored this and just swirled his whisky glass. “Me da’ was an admiral,” he said. “He had to earn his rank in the Navy because his no-good brother got Newstead. Foul-weather Jack, they called my old man. He knew how to keep his keel level through twenty-foot swells. And look at me. I had to marry a disgusting cow like you to get the funds to keep myself soaked in spirits. And the son you gave me: he’s worthless, ain’t he?”

My mother braced my weight against her ample hip and pouted at my father. “I don’t see why you’re so horrible to me and the boy, so bent on destroying yourself. We had everything we needed to be happy, before things started falling apart.”

“Nothing fell apart,” he said. “I ruined it, intentionally and out of spite. None of it was worth preserving in the first place.”

“You ruined us, Jack.” She brandished me at my father. “What sort of future will there be for him?”

“There isn’t any future, not for him or anyone else.” He caught a glimpse of his reflection in the side of his glass; his nose webbed with broken red veins, his brown teeth protruding like desiccated stumps from the infertile clay of his purple-gray gums. “Ruin comes whether we court it or whether we cower. Might as well drink while we can afford a bottle. We’re all just staggering toward death.”

“Not you, Papa,” I said. “You’re going to live forever. You know the gypsy secrets. You know about the vampires.”

One of the workmen approached. “We’ve got to take the chair, too, Mr. Gordon,” he said.

“Mr. Gordon,” my father repeated, and he laughed. “I wasn’t born Gordon; I was Byron. Gordon is hers.” Here he pointed an accusing finger at my mother. “I had to take her surname to get her money. And now, of course, the money’s gone, and I’m left with nothing but a fat wife, a crippled son, and somebody else’s name.”

The man rubbed his hands across the front of his canvas trousers as he tried to decide what to say. He came up with: “Your name ain’t no concern of mine, sir. I just need the furniture.”

My father stood, his motion remarkably smooth and deliberate, considering his drunkenness. He drew his second pistol and fired it at the chair. The ball struck the place where the back met the seat, sending an explosion of slivers and cushion fluff into the air. My mother was hit by shrapnel in several places, and I got a thick chunk of wood stuck in my forearm, and another in my side. I began to cry.

“Have the sodding thing, with my blessing,” said my father to the workman, and he threw his crystal glass against the side of the house. Then, to my mother: “Take the child away. I can’t stand to look at it any longer, or listen to the sound of its mewling.”

At sunset, she brought my supper to my bedroom, and I ate it alone, as the governess had left several weeks earlier for want of pay. I did not see my father again that night, and when I awoke the next morning, he’d left us and fled the country. Had he stayed, he would have been imprisoned for his unpaid debts.

The castle at Gight, which had been Catherine’s inheritance, went to my father’s creditors. When she met Mad Jack, she was a wealthy heiress with a substantial income. Now, all that was gone. My mother was willing to give up everything for love, so love found her a match who was willing to take everything from her. My father, despite his other flaws, was not lacking in imagination, and he put his creative faculties to good use, devising new ways to spend money and accumulate debt. Once he’d stripped away her assets, my mother was no longer of any value to him.

Soon after he left, I heard he had died. There were rumors that he was murdered by the husband of his mistress. I never believed it, though. My father always said that only foolish men die. Whatever else he was, Mad Jack was no fool.

Chapter 8

I loved-but those I loved are gone;

Had friends-my early friends are fled:

How cheerless feels the heart alone,

When all its former hopes are dead!

Though gay companions o’er the bowl

Dispel awhile the sense of ill;

Though pleasure stirs the maddening soul,

The heart-the heart-is lonely still.

- Lord Byron, “I Would I Were a Careless Child”When I returned to my residence, the man from London was waiting there for me.

“I am Sir Archibald Knifing,” said my new friend as I entered. Joe Murray looked irritated; it was his customary duty to introduce guests, and it was rude of Knifing to dispense with proper etiquette. But Knifing didn’t seem like a man with much respect for protocol or much tolerance for inanities. He didn’t seem like the kind of man one wants to meet when one has just lugged a heavy wooden chair up several flights of stairs after stealing it, either.

I shrugged off my greatcoat, which Joe Murray retrieved from the floor, and I pushed the throne against a wall in the parlor. I draped my body over the seat, trying to look as impressive as I could under the circumstances. My clothes and hair were damp and clingy.

Knifing remained almost unnaturally still as he watched me arrange myself. He had a sallow and waxy complexion; skin like that of an embalmed corpse, except for a puckered pink scar that sliced diagonally across his face, from the middle of his forehead, through his milky left eye, and down the side of his cheek. His clothing bore the hallmarks of the finest London tailors, but his suit was black, which was out of fashion for social calls during daylight hours, and so snug around his emaciated, cadaverous form that I was surprised the man could draw breath. In his hands, he held a wide-brimmed black rabbit-felt hat, and a long-handled umbrella hung by its curved handle from his forearm, though it had not been raining. Joe Murray would certainly have offered to take charge of such objects upon a guest’s arrival. I assumed Knifing had refused to relinquish his accouterments, which was curious.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Riot Most Uncouth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.