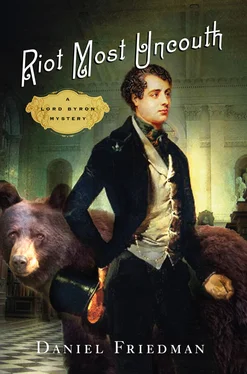

Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Riot Most Uncouth

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9781250027580

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Riot Most Uncouth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Riot Most Uncouth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Riot Most Uncouth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Riot Most Uncouth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Hello, Professor Brady.”

“Lord Byron,” he said. “I’m pleased by the news that you’ve been exonerated, as I understand it, of all those nasty accusations. I was somewhat aggrieved, however, to learn that kindly Mr. Buford was responsible for the killings. I knew him a little bit, and never would have suspected. I commissioned quite a bit of carpentry from him; a number of lecterns and desks and chairs for the College. Perhaps I shall have to replace them now. Regardless, I’m pleased to see you back in Cambridge.”

“I don’t intend to stay here for long,” I said.

“As I’ve told you, I’d consider it a grievous error in judgment for you to abandon your studies.”

I spoke without waiting for him to ramble out another disorganized thought. “Nothing will be abandoned. My studies will be finished in top form, and I’ll earn all the most prestigious prizes and Latin honors your department is empowered to confer upon me. I just won’t be spending any more time in Cambridge.”

“I don’t understand,” Beardy said.

“Let me explain it simply, then,” I said. “If you’d like, you may consider this my thesis project: It would have been difficult if not impossible for Angus Buford to kill Cyrus Pendleton on the same night he massacred the Tower family. The massacre, you see, would have been quite a time-consuming enterprise. The killer needed to drag the corpse of Professor Tower from the bedroom to the dining room, and pose it at the dinner table. He had to drain the blood from Mrs. Tower’s corpse, and then he had to carry a sloshing bucket of the stuff to the foul vat he had concealed in a rented room all the way across the city, at the Burning Tyger Inn. Pendleton was seen inside the Modest Proposal alive at half past ten. The Towers’ housemaid opened the door to Buford. She would not have been awake much past eleven. The tavern closed at midnight. The timing of the murders is confusing.”

“What are you suggesting?”

“Angus Buford did not kill Cyrus Pendleton,” I said.

“This is really absurd.”

“Pendleton had pushed you out of the College, hadn’t he? He’d taken over your position. You were to be sent off to your pension and your dotage. A just reward for a long and distinguished career.”

“I don’t think I like what you’re insinuating.”

“I’m only saying that, in the wake of this sudden and unfortunate tragedy, it’s quite noble of you to delay your well-earned retirement and stay on as the head of the department.”

“Can you prove these incredible allegations?”

“Proof is a malleable thing, Professor. You show people a set of facts that makes sense, and they’re apt to believe it,” I said.

“This is slander. This is entirely baseless. This is-”

I interrupted him again: “This is ruinous, once the allegations are uttered in public, and I’m sure you understand that.”

“You’re a monster.”

“We’ve both killed men this week, Professor Brady. Let’s not go putting ugly labels on things, though. My silence in this matter has a price you can afford.”

“Diplomas. Prizes. Latin honors,” he said.

“And a fellowship for my bear. It doesn’t need to have a teaching component. Just a sheepskin denoting the honor, and a reasonable stipend to fund his studies.”

“You’re depraved,” said Old Beardy.

“Well, I learned from the best,” I said. “Or, at least, the best outside of Oxford.”

“Blackguard. Extortionist. Mad, lame, drunken thief.”

“I’m pleased you find my terms acceptable. My lawyer will be contacting you to handle the details. Good day,” I said. And I stood and strode out the door, keeping my gait as smooth as my weak leg could manage. Blood was singing in my ears as I burst through the front door of the building and out onto the manicured carpet of the College’s Great Lawn.

My body was bruised and my head was concussed and I was sick to my stomach, but nonetheless, I felt liberated. My finances were now in better repair than they’d ever been, my education was complete, with top marks, and my future was spread before me. I turned my face toward the late afternoon sun and closed my eyes. I could go wherever I wanted.

A few weeks later, I went East.

Chapter 42

I have a personal dislike to Vampires, and the little acquaintance I have with them would by no means induce me to reveal their secrets.

- Lord Byron, from an 1819 letter to the editor of Galignani’s MessengerArchibald Knifing delivered the money he promised, and that run of fortune paid for my adventures in the Levant, which inspired me to write Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, a work of enormous and incontrovertible literary import.

However, I searched the London papers for reports about tragedy in the family of some earl or viscount, and I found no death-notice that could possibly have described the man whose name was not Frederick Burke. This seemed strange, but the wealth of those close to the Crown could buy a lot of discretion, and it was not unheard of for a shameful death in a well-heeled family to go unheralded in the press.

So I listened for gossip. While Knifing would not tell me whether Not-Burke was an heir or a younger son, the death of anyone in line to inherit an important title was always much discussed among certain social circles. Wild fluctuations in the marriage market would necessarily ensue in the wake of such a tragedy. Various players would have to reconsider their strategies. Some younger brother or close cousin would be a step closer to inheriting, and the prospects of all eligible relations to the decedent would need to be recalculated. But I heard no discussion of any death that could possibly be Not-Burke’s. Perhaps, if Not-Burke had been formally disinherited, he could have died and been buried without much fanfare or outside interest, and such an act by his father may, indeed, have been the fount of Not-Burke’s rage.

But still, the mad, disgraced son of an earl would be of implicit interest to gossips, and the death of such a figure would ordinarily be, at the least, fodder for much idle conversation. The silence surrounding these events was suspicious.

But I had sworn myself to secrecy and could, thus, undertake no further inquiry into the matter. Asking questions would break my promise to Knifing. So I set out for the Continent and left my thoughts about the man I’d killed behind, along with my mother and the Professor.

It was years later, as my fortunes and my marriage and my reputation came unspooled that I began to reconsider everything that had occurred in Cambridge. I had recently vacated Newstead after separating from my wife, and I discovered William Byron’s big black wardrobe among the effects Annabella had sent to my new lodgings in London. I still had a key to the sturdy padlock, and I found my arcane texts undisturbed inside.

As I had lapsed into solitude and melancholia, I found myself with ample time to consider the Cambridge murders, the vampires, and the fate of my father. Breaking, for the first time, the promise I’d made to Knifing, I began recording my narrative of those dark events.

Among my collection of vampire lore were certain tracts that discussed the habit among vampires to employ weak-willed men as thralls or familiars; hypnotized slaves tasked with seeing to the monster’s interests while it slumbers. These men gradually lose their minds as their wills are broken by the vampire’s influence, and they are known to subsist on insects and rodents and the festering remains of drained victims.

As I sat amidst the detritus of my ruined life, I reconsidered these materials and convinced myself that the wild-eyed Mr. Not-Burke, bathing in sour blood and covered in flies, may not have been the monster he seemed, but rather, merely an ordinary man under the power of such a nefarious spell.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Riot Most Uncouth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.