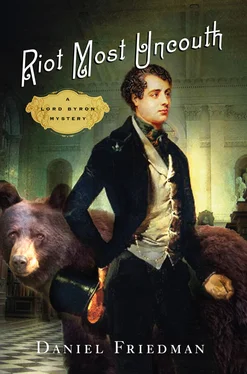

Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Riot Most Uncouth

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9781250027580

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Riot Most Uncouth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Riot Most Uncouth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Riot Most Uncouth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Riot Most Uncouth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As Joe Murray showed him out, the Professor looked at me and let out a noise like distant thunder from someplace deep in his throat.

“I’m quite aware he will be back,” I said.

The bear snorted.

“No, I’m not sure yet what I am going to do about him.”

Chapter 4

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air

- Lord Byron, “Darkness”“Financial prudence is the virtue of those who lack imagination.” That’s something my father often said, usually punctuating the statement with a violent gesture and spilling his drink in the process. “I pity the sad bastard who dies without any debt. He hasn’t really lived.”

I was too small to understand most of his quips at the time, but I remembered them, parroting his manner and his speech in front of my bedroom mirror when I was alone. I wanted very much to be like him; he was so self-assured, and other adults seemed to take him very seriously. He was always surrounded by a crowd of friends and associates, and they always roared with approval when he told his stories. It seemed his personality itself was a radiant and mysterious force that drew these people to him; it was only much later that I came to understand that his charisma was helped in no small measure by the fact that he paid for all the booze.

He was a great man, though. He had a voice like a church bell and a fist like a hammer, and he made frequent use of both these gifts. He continued our family’s military tradition; a captain of the guard and the son of an admiral. The soldiers who’d served under him called him Mad Jack, and not just for his fury in battle.

If he was never affectionate, he was always boisterous, except when he was hungover, of course. While he dwelt at my mother’s Scottish estate, the place bubbled with constant activity; an endless parade of visitors and servants. Mad Jack was surrounded by strangers, and I, a small boy, was generally left to my own devices, or else locked in my room. My mother cared for me when she could, but she spent a lot of time alone, weeping. She was weak, and she could never equal his wit or satisfy his appetites. But my father made sure he always had plenty of liquor and girls around. He said these things gave him what my mother couldn’t.

I rarely knew sleep in my earliest years; every night, the house would writhe with activity and pulse with noise. I remember lying in the dark, in my room, and listening to the sound of revelry all around me: stumbling footsteps in the corridors as men chased girls into various unoccupied rooms; laughter and yelling; the thrumming of strings and the pounding of drums-my father always hired the best musicians. And above it all, I could always hear his voice reverberating, clear early in the night and slurred later, but always authoritative.

One June evening when I was five years old, I climbed out of bed and found my mother had forgotten to lock my door, so I ventured forth to see the party. In the hallway outside my bedroom, two men were pawing at an unconscious woman. I followed my father’s voice out to the courtyard, moving slowly to keep the brace on my leg from squeaking. I was frightened a little, for the adults were staggering about the house and vomiting in chamber pots. It was dark, too; the only light in the courtyard was from torches mounted on poles. A string quartet was playing an Austrian waltz, and some of the guests were lurching around, making drunken attempts at dancing.

“Death is not an inevitability,” my father was saying. “It is merely a likelihood.” He had draped his lanky frame over a high-backed wooden chair, and his friends were seated on the grass at his feet, waving crystal glasses at him, which he refilled with sparkling wine from a large green bottle. A young woman sat on his lap and was licking at his neck.

“I have been to the East,” he said. “There are men, or things like men, in that region who have conquered death. They taught me their secrets. Mortality is for the foolish and the poor. Decay is a consequence of individual failure. A man ought to control his destiny, and not be victim to circumstance.”

The crowd at his feet raised their glasses. “’Ave at ’em, Mad Jack!” shouted one of the drunks.

“I am not a fool, so I submit that I will live forever.” With this, my father grabbed the girl by the throat and kissed her, hard on the mouth. “The rest of you bastards can give my regards to the Devil.” He pressed the champagne bottle between the girl’s thighs, and she gasped at the touch of the cool glass.

I dodged among the crowd and grabbed at his hand. “I want to live forever, too, Father,” I said.

He looked down at me, and his upper lip curled. “Who let you out of your room?” he asked. Then, with a violent wave of his hands, he summoned one of the nearby servants. “Fetch my stupid cow of a wife.” He dismissed the girl on his lap with a slap to her rump and made a show of rolling up his shirtsleeves.

My mother appeared a few minutes later, clad in her nightgown, her hair disheveled. Unwelcome at my father’s party, she had been asleep. “Why are you out of bed, little George?” she asked me.

“He is out of bed because you are so bloody worthless that you are incapable of putting him in his room and locking the door.” He rose from the chair and struck her face with the back of his hand. She fell to the ground. The party guests burst into laughter and applause.

“You continually embarrass me with your inability to perform the simplest tasks,” he said. “I ask so very little of you, and yet I get even less.” He grabbed me roughly under my arms and carried me back into the house. My mother followed, sobbing, behind him.

“Father, you’re hurting me,” I said.

“I ought to put you in a sack and drown you in the river,” he told me.

I wanted to cry, but I was too scared. He threw me on the floor of my room, and my bad leg twisted under me as I fell. The door slammed, I heard the key turn in the lock, and I was alone.

In the hallway, he was still yelling. I couldn’t make out all the words, because the door was heavy and the guests had followed us down the hall, making noise and hooting. But among his shouts, I understood “deformed,” “lame,” and “disgrace.”

Chapter 5

I have got a new friend, the finest in the world, a tame bear. When I brought him here, they asked me what I meant to do with him, and my reply was, “he should sit for a fellowship. …” This answer delighted them not.

- Lord Byron, from an 1807 letter to Elizabeth PigotThough Trinity College had failed me in many ways, the school had at least attempted to provide accommodations that were not totally insulting. My rooms were in Nevile’s Court, by far the most prestigious residential building at Trinity, which was the most prestigious college in Cambridge. Sir Isaac Newton himself had dwelt in this very edifice, and had calculated the speed of sound by timing the echoes of his footsteps in the north cloister. I was close to the riverbank, where I could swim. The other building residents were gentle and well heeled. Except, of course, for the bear.

I was also relieved of the obligation to take meals in the common hall, when I preferred to dine alone or entertain guests in a more intimate atmosphere, for my suite had a kitchen where my servant could work his alchemy, and a dining room that was adequate for the presentation and enjoyment of fine cuisine. My table was large and constructed with consummate skill from fine, even-grained hardwood. The linens and the silver were of exquisite quality. Were it not so, I would have been embarrassed to play host to so distinguished a personage as the Professor.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Riot Most Uncouth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.