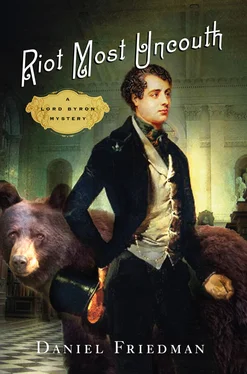

Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Riot Most Uncouth

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9781250027580

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Riot Most Uncouth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Riot Most Uncouth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Riot Most Uncouth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Riot Most Uncouth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“That was much flimsier than I was led to believe,” Dingle remarked. He seemed quite surprised that he’d been lied to. For a professional criminal investigator, he was an absurdly credulous man.

“I shall remember that the next time I need to escape from prison,” I said. “Now, if you enjoy being alive, kindly unlock my shackles so I can climb up there and rein in the horses.”

“I must not,” he said. “You are a prisoner, and will remain in your bonds until I deliver you to the court. I will take care of this myself.”

Dingle hoisted himself out through the open doorway and perched on the running board along the carriage’s lower chassis. Dangling precariously over the road, he reached out for one of the ladder rungs that were bolted to the side of the cab, and he began to grunt as he tried to lift himself up onto the roof. I had about five seconds to admire his bravery before I heard a second shot, and Dingle’s head came apart. I saw him hanging, ever so briefly, in midair. The top of his skull and one of his eyes were gone, and part of his nose as well. Whatever struck him had done so with unbelievable force. The thick, wet lips hung loose and sort of flapped in the wind. What remained of his face wore an expression of confusion and incomprehension; he was as dumb in death as he had been in life.

The corpse pitched off the side, fell beneath the wheels, and burst like an overfilled meat-pie when the carriage rolled over it. The force of the impact bounced the whole vehicle into the air.

“He was right,” I said, vocalizing my thoughts to no one and for no particular reason, as I hung in space, tethered to my bench by chains, “about being doomed.”

And then, the stagecoach crashed.

Chapter 32

And there lay the steed with his nostrils all wide,

But through it there roll’d not the breath of his pride:

And the foam of his gasping lay white on the turf,

And cold as the spray of the rock-beating surf.

- Lord Byron, “The Destruction of Sennacherib”The floor became the ceiling and the ceiling became the floor, and then things righted themselves briefly before the carriage rolled again. I didn’t know up from down; I lost track of the world and forgot my place in it. Then everything fell to earth, and splintered and broke apart.

Angry hunks of wood slashed the thigh of my weak leg and raked my back and pounded my side hard enough to knock the breath from my lungs. When the stagecoach finally flipped sideways and skidded to a halt someplace off the side of the highway, I assessed my injuries. My ribs were bruised, but they had not caved in. The manacles had cut into my wrists, but my arms were not broken or dislocated. My head felt as if it might have been concussed, but it was in considerably better repair than the skull of Fielding Dingle. My cuts were seeping rather than gushing or pumping blood, which meant my wounds would not be mortal unless some putrefying infection set in.

I suppose I must consider myself lucky to have come through that ordeal largely intact, though perhaps I was less lucky than the millions of people who have never found themselves injured in the wreckage of a stagecoach someplace between Cambridge and London.

And I had other problems. I was still chained to my bench, and I didn’t know where the keys to my shackles had gone. Either Dingle or the driver had been carrying them, and both their corpses had fallen off the vehicle, someplace back down the road.

I wrenched my arms so I could peer out through the kicked-out door, but I didn’t see anything but the field I’d crashed in and the road, away in the distance. The keys could be miles back, lost in thick underbrush. And even if they were nearby, I had no way of finding them.

One of the four horses that pulled the carriage had snapped its leg. It was lying in the grass fifty yards away and bleating in agony. The other horses had broken free of the harness and bolted off.

I tried to take an optimistic view of what seemed a dire situation. If I were stuck in the wreck for longer than a day or two, I was bound to die of thirst or exposure. But before that happened, somebody would probably find the corpses on the road, or else someone would hear the dying horse and come to investigate. Until then, I could only wait.

My head throbbed and my body ached. I suppose I dozed intermittently. Several hours must have passed, though I had no sense of it, for when Angus the Constable found me, night had fallen.

I heard him before I saw him. More precisely, I heard a gunshot when he put down the injured horse. His first attempt didn’t do the job, so I heard the loud crack of it, and then the animal’s muted whimpering turned into a terrified, high-pitched scream, which it sustained for the entirety of the two minutes it took Angus to reload. I remember thinking it was strange that a brute animal’s howl of pain and terror could sound so familiar and so human, and I thought of poor Violet and her children, who never got a chance to scream. The noise ceased only when the constable shot the horse a second time.

Then, Angus’s flinty black eyes and round red nose appeared in the splintered doorframe of the stagecoach. He looked ashen and somewhat discombobulated, but he gurgled with relief when he saw I was alive. “You seem to have encountered a nasty bit of business, Lord Byron,” he said.

“I hope it is evident to you that I did not kill Dingle,” I said, jangling my shackles and showing him that I was still bound to the bench. “I have been indisposed since I last saw you in Cambridge, and have, since, endured some injury. What are you doing here?”

“I patrol the highways most nights,” Angus said. “Someone has to keep the lookout for road agents and bandits.” He proudly brandished the musket he’d used to kill the horse, and I wondered if he could have used that to shoot Dingle off the side of the carriage. He’d have needed preternatural luck to make a shot like that; and even the luckiest man alive couldn’t have done it twice. But somebody had shot both Dingle and the driver, a feat of marksmanship that seemed beyond the capacity of any human skill.

A musket’s barrel is quite a bit wider than its bullet, a necessity for fast reloading through the muzzle. As a result, the ball has a tendency to bounce around in the tube on the way out, which makes it impossible to control the direction of the shot with any degree of finesse. Muskets are effective when a lot of them are fired simultaneously in the general direction of a large group of enemies, but a single musketeer facing a single enemy would make himself an immeasurably greater threat by affixing his bayonet, or simply drawing his saber.

I didn’t think Angus could have killed both men with only two shots, or even with twenty. Maybe he could have if he were a vampire; some of my texts said the undead possessed monstrous strength and extraordinary reflexes.

“Ever find any road agents?” I asked the constable.

“No,” he said. “They strike sometimes on the highways around Cambridge, but I’ve never arrived at the scene of a robbery in time to apprehend the bastards.”

“What will you do if you find them?” I asked.

“Kill them,” he said. “I’ll kill every last one.” This was a ridiculous proposition, and if I’d been in my usual state of boozy levity, I might have laughed right in Angus’s thick, earnest face. But there was something distinctly unfunny about his tone, a strain or a hitch, as if he was trying to flatten some swell of emotion.

“You think road agents waylaid this carriage?” I asked.

“Wouldn’t reckon so,” Angus said. “Little profit to be had from robbing jailers or prisoners. And when I found the bodies up the road, nobody seemed to have rummaged them. I think the gunman is the killer from Cambridge.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Riot Most Uncouth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.