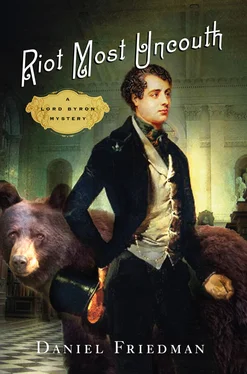

Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Riot Most Uncouth

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9781250027580

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Riot Most Uncouth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Riot Most Uncouth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Riot Most Uncouth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Riot Most Uncouth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The aspersion against my father tensed my entire body and set my vision double. Blood roared to my ears. How dare this foolish child impugn the honor of one of Britain’s greatest heroes, even as he undertook necessary and dangerous adventures abroad on the State’s behalf, which kept him away from his devoted son?

“Take it back!” I yelped as I leapt to my feet. The audible creaking of the metal leg-brace beneath my trousers undercut the effect of my rage. “My dad never murdered anybody. He’s a soldier and an honorable man.”

“He ain’t a soldier anymore,” she said. “He’s just dead.”

“He’s not dead,” I said. “Only those without imagination ever die.”

“The real Lord Byron-the old Lord Byron-is still alive?”

“Oh. No, he’s dead. He wasn’t my father. He was my great-uncle.”

“Well, that still means your father is dead.”

I was incensed. “How would you know that?”

“If he were alive, he’d have become the Lord Byron, and not you.”

I tried to stammer something about vampires and the Gypsy legends of the East, but she just laughed at me.

“I can promise you that everyone dies,” she said. “Your father told you a fanciful story.”

I would say that was when I first loved Mary Chaworth. She represented, to me, the allure of adulthood; the stripping away of the pretty lies of childhood to perceive the world as it truly is, even if I had no intention of shedding my illusions.

Clergymen say the desire for knowledge is the Original Sin, and that was certainly the case for me. Like Adam’s, my pursuit of Knowledge came at the behest of a woman. Ever since Mary Chaworth, the scent of perfumed flesh and the warm touch of it beneath my fingertips has reminded me of the fact that I would not endure forever. Awareness of death, I think, mingles passion with urgency.

“So, what about the sword?” asked Mary on that sun-dappled afternoon in my distant, formative past, sitting in the grass with her legs tucked coyly beneath her ruffled skirts.

“What sword?”

“You don’t know much about Lord Byron, do you?”

“I am-”

“No, the real Lord Byron.”

The sword, as it turned out, was part of a rather comical bit of family lore. My great-uncle had a neighborly dispute with Lord Chaworth, Mary’s grandfather, on the subject of whose lands were more abundant with game. My uncle was determined to resolve this argument, and did so in a rather clever manner: He got roaring drunk and disemboweled Chaworth with a sword, in full view of a number of witnesses, at the Stars and Garters tavern in London.

As punishment for the murder, my uncle spent two years imprisoned in the Tower. Murder is a capital crime, of course. But in England, nobility is still respected. Only commoners get executed.

They say Lord Byron felt winning the argument was worth the two years. When he returned to Newstead, he hung the murder weapon above his bed as a trophy, and when my mother and I inherited the place, we left it up there to collect dust and cobwebs. Mary found some sort of macabre delight in looking at it.

“The Byron name has come to stand for cruelty and senseless, remorseless violence,” she told me. “You’ve got a grand legacy to live up to.”

How could I do anything but love her?

Three summers later, I was somewhat more mature, and I decided that Mary Chaworth was my muse and that I was destined to spend my life with her. I refused to return to Harrow, because I could not stand to be apart from my beloved. But, thanks to the peculiar acoustic qualities of some of the larger rooms at Newstead, I overheard her from some distance away, saying that she cared nothing for “that plump, lame, bashful boy lord.” She was soon after engaged to a gentleman named Musters, a man known for his dubious morals and questionable finances.

This destroyed me utterly. I had given this girl a piece of my heart, and she took it and locked it away in a dusty cupboard. And throughout all my affairs and adventures that followed, I could never again give that piece of my heart to anyone else, for she had it and it was hers forever, though she cared nothing for it.

It was because I was unworthy of Mary Chaworth’s love that I began swimming miles in icy waters in wintertime, and running great distances in layers of heavy clothing in hot weather.

I ought to drown you in the river.

It was because I was unworthy of Mary Chaworth’s love that I stopped eating and started drinking. It was because I was unworthy of Mary’s love that I began serially fornicating with near strangers.

Deformed. Useless.

It was because I was unworthy of Mary’s love that I spent lavish sums, often borrowed, buying custom shoes that hid my clubfoot.

A physical manifestation of my failings and inadequacies.

So, if anyone ever wonders why it is that I am the way that I am, it’s because Mary Chaworth couldn’t love me.

Chapter 28

I am buried in an abyss of Sensuality. I have renounced hazard however, but I am given to Harlots, and live in a state of Concubinage.

- Lord Byron, from an 1808 letter to John HobhouseA woman’s undergarment is an intimidating device to confront when one is very drunk. After fumbling with Noreen’s corset for a few minutes, and finding my situation growing extremely urgent, I solved the problem with my knife. The taut laces popped under only a little pressure, and the restraining mesh of quilted linen came free. I threw it to the floor, where it fell in a sad little heap. Mastery of the thing gave me a grim sense of satisfaction; it reminded me of the torturous contraptions that quack doctors inflicted upon my poor leg when I was a child.

“Byron,” she protested, “those are quite expensive. Why must you ruin everything?”

“Because I don’t care about things,” I said. “And it isn’t ruined. It merely needs relacing.”

Her body smelled of powder and female excitement, and her skin was damp and flushed. I pulled her to me and kissed her hard upon the mouth as I pressed my hand beneath her skirts. She was fumbling with my trousers.

“You must remove your boots,” she murmured.

“Of course,” I said. But first, I blew out the lamp so she would not see my shriveled right foot.

I climbed on top of Noreen and moved to kiss her, but she pushed me away. I swore a nasty oath at her as I covered my leg with the blanket and reached down to the floor, feeling around in the darkness for a shoe.

“No, it’s not that,” she said, wrapping her arms around my neck and pulling me back onto the bed. “It’s just that he’s watching us.”

I turned around and saw the hulking form of the bear, who had wandered into the room. He was nudging the girdle around on the floor with his nose.

“Darling, I assure you, the Professor’s interest is purely academic.”

But her protests continued, and so I climbed out of the bed, taking the blanket with me to hide my leg from her. I coaxed the bear out of the bedroom, down the hallway to his study. He grumbled with protest at his exclusion from the evening’s recreation.

“I know,” I said. “But the girl requires privacy.”

He nodded, and rubbed his bristly haunches against my great-uncle’s sinister black cabinet before retreating to his pile of bedding in the corner of the room.

“Thank you, Professor. That is a fine idea, and you are gracious to suggest it, under the circumstances.”

I unlocked the cabinet. On the highest shelf was my green absinthe bottle. In a hidden drawer, there was another bottle; a small gray one with a glass stopper. I knotted the blanket around my waist and carried both bottles back to the bedroom.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Riot Most Uncouth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.