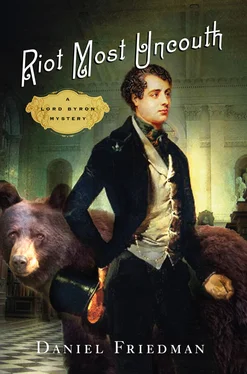

Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Daniel Friedman - Riot Most Uncouth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 0101, ISBN: 0101, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Riot Most Uncouth

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:0101

- ISBN:9781250027580

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Riot Most Uncouth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Riot Most Uncouth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Riot Most Uncouth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Riot Most Uncouth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I locked my gaze with Whippleby’s; stared into the deep hollows around his eyes and at the pinched, mealy-white flesh of his face. This man was wrecked, and I was partly responsible. I’d told a lie I believed was insignificant; Felicity Whippleby and the other Cambridge victims had gotten a sort of justice. There seemed to be little harm in manipulating a few of the facts.

But this old man perceived the falsehood, and the lie had devoured him. He needed to know what had happened to his daughter, just as I needed to know what had happened to my father. And so, he’d ruined his mind and wasted his vitality trying to unravel a conspiracy I’d been a part of. We had offered the perception of justice, of certainty. And, as Knifing might have predicted, the others bereaved by the Cambridge murders had accepted it and found it comforting. But Knifing had been wrong about Whippleby. What the dead girl’s father needed was the truth.

On one level, I had visited Whippleby to find an emotional center for my narrative of the murders. I didn’t really know Felicity, and she was already dead when I entered the story. Thus, she was an abstraction within the narrative. The murders and the process of their resolution, to the reader, seemed to merely be sort of a puzzle, and this made everything that happened afterward seem unimportant. I’d gazed upon the corpses with my own eyes and I’d filled my nostrils with the stink of their decay, so the pursuit of justice, as I experienced it, had had an urgency that I failed to convey upon the page.

More than once, in the course of writing my polemic, I’d wished I’d spoken with Felicity’s mourners in the days after she was killed instead of running around uselessly in a drunken frenzy. Archibald Knifing, with the assistance of Angus the volunteer constable, interviewed Felicity’s close friends and her neighbors in the rooming house to try to reconstruct the events of her final hours. I will admit that it never occurred to me to do so. Just as, only a few years after the installation of gaslights, one can no longer imagine the streets of London dark and empty at night, it seems strange to recall that protocols of criminal detection have been only recently established, and to the extent they existed in 1807, they were certainly unfamiliar to those outside the fraternity of investigators. So, while readers of the mystery stories that now proliferate in the popular press may think it elementary to interview a victim’s associates as a first step in investigating a murder, it was by no means the obvious course of action for me in Cambridge.

But there’s no point in defending myself. Because of my investigative omission, I knew very little of Felicity Whippleby, and I needed more information to write about the events surrounding her death. I’d hoped the girl’s father might provide me with some anecdote; some story about a sweet or precocious child that would become maudlin when placed opposite a depiction of the horrific details of her demise. If I could not fully convey my own visceral alarm on the page, perhaps I could instill in the reader some of Lord Whippleby’s gnawing sense of loss.

But seeing the wreck that Whippleby became helped me realize that the story was never about his daughter, and I had portrayed her as unimportant because she never really had been important. The story I needed to tell about the Cambridge murders was about me and about my father, and about the choice I made.

My instinct that my narrative was incomplete had brought me to Whippleby, but the problem was not with the beginning of my tale, but rather, the ending. There was no new information for me to uncover in Whippleby’s dirty London rooms. I’d come, instead, for some measure of redemption.

I’d spent years pondering the things I did over the course of those few days when I was nineteen, things I’d never spoken of to anyone. It was no coincidence that I had begun writing about what happened at Cambridge when my personal fortunes were at their nadir and my reputation was in tatters. I would not continue to lie, not to the world, not to Whippleby and not to myself. I would tell this man my secret and, thereby, atone for the wrongs I had committed and the scheme in which I had been a participant.

Doing so would endanger me, perhaps. And it certainly meant that my planned exile from England would no longer be voluntary. But that was fine. I was done with lies and I was done with the rainy, squalid islands of Britain and the small-minded people who dwelt on them. Redemption seemed a worthwhile goal, and there was a whole unspoiled Continent to explore.

“There’s no mystery to unravel,” I told Whippleby. “I know which investigator was false, and I know whose interests he served. And I know who really killed your daughter.”

Whippleby wet his lips with his tongue and leaned toward me. His eyes bulged, and his hands quivered.

I told him everything.

Chapter 21

She walks in Beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes:

Thus mellow’d to that tender light

Which Heaven to gaudy day denies.

- Lord Byron, “She Walks in Beauty”After arranging to release the bear into Joe Murray’s custody, I accompanied Angus and Knifing to the scene of the latest atrocity. The place was familiar to me; it was the residence of Professor Tower and his family. Indeed, Professor Tower was the first person I encountered upon our arrival there, though I did not immediately recognize him. I typically identify people by their faces, you see, and Tower was missing his.

“I didn’t even know a face could come off like that,” said Angus as he stared at the grinning skull, which was a wet yellowish-brown color with patches of red flesh still clinging to it. The rough and messy surface was quite unlike the smooth, polished interior of my Jolly Friar, but having drunk from that vessel on so many occasions, it turned my stomach to see a human skull in its natural state.

Angus had said there was not just one killing, but rather, “a massacre.” This was not the only body here to be examined. Though I was feverishly trying to imagine some circumstance by which my paramour had escaped her husband’s fate, I felt a near compulsion to fall to my knees and wail with anguish. I restrained myself, however, and maintained a bearing that suggested no emotion more intense than mild curiosity. Neither my interests nor her memory would be well served by the revelation of our indiscretions.

“The face is less than an eighth of an inch thick, and it’s only stuck to the bone with soft, mobile tissues,” Knifing was saying. “All you need to loosen it up and get underneath is an incision along the hairline or beneath the jaw. If you can work your fingers into that, the whole thing will rip away with a good pull, especially if you’ve practiced the movement.”

“Why do you know this?” I asked. What I was thinking was: One requires only a sturdy ax, a large pot of boiling water, and a strong stomach.

“Knowledge of anatomy and other modern sciences are crucial to my profession,” Knifing said. “I’ve participated in a number of autopsies. And in my former life as a soldier, I learned exactly how deep my own face went.”

“You were cut all the way to the bone?” Angus asked.

“There is a notch, a groove in the skull beneath my scar. With only a bit more pressure, the wound would have been lethal.”

“Mortality is for the foolish and the poor,” I said, because the recitation had become almost a reflex. “Decay is a consequence of individual failure. A man ought to control his destiny, and not be victim to circumstance.”

Knifing’s dark eye narrowed, but his white one seemed to widen. “Those are the words of a man who has never experienced the horrors of modern warfare. Wedged into an infantry formation, there’s no place to run when musket balls fall upon you like hailstones, and there’s little one can do to evade a shot from a cannon. I’ve seen plenty cut down in battle; braver and better men than you. Their sacrifice was no failure, and nobody living has a right to call them fools.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Riot Most Uncouth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Riot Most Uncouth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.