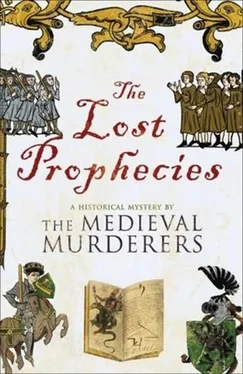

The Medieval Murderers - The Lost Prophecies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Medieval Murderers - The Lost Prophecies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Lost Prophecies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Lost Prophecies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Lost Prophecies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Lost Prophecies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Lost Prophecies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Shortly after, the brothers returned. One carried a large leather bag. With them was a tall, craggy-faced older man who walked like a soldier. Shiva was surprised to see that he held a bowl of food in one hand, a spoon sticking out. He could smell something like chicken. In his other hand the man carried a bottle of water. He laid both beside Shiva.

‘Hungry?’ he asked. He had a Tasman accent. ‘I guess you’re thirsty too?’

Shiva picked up the water, drank it, then took the bowl clumsily on to his lap. It was difficult to hold the spoon in his bound hands, but he managed, though he spilled some food down his shirt. He ate the meat and started on the thin, fatty stew underneath, but after a few mouthfuls he felt nauseous and had to put the bowl down. He wondered if it was a sign of radiation sickness.

The man turned and nodded to the brothers. They left the room, the one who carried the leather bag putting it on the floor. They locked the door behind them. The soldierly man sat on his haunches in front of Shiva. His eyes were calculating. ‘My name is James,’ he said. ‘I want to ask you some questions.’ His voice was gentle. ‘How are you feeling? They said you hurt your shoulder on the journey?’

‘Yes.’

‘OK.’ James nodded, then turned and picked up the bag. He pulled out a rope and a knife. He used the knife to cut the bonds on Shiva’s left hand, then quickly and expertly, giving him no time to react, he hauled Shiva’s left arm up behind his back, looping a second length of rope around Shiva’s neck and securing it to his wrist, fixing his left arm up behind his back. He cried out at the pain in his left shoulder.

James leaned back on his haunches. ‘An incentive to answer my questions,’ he said in the same quiet tones. ‘Now, how did you find out about Parvati Karam?’

Shiva had been taught about dealing with torture. The main point was that in the end nearly everyone gave in. The pain in his shoulder made it hard to catch his breath as he told the story he had formulated. To begin with, what he said was true: how Parvati had been seen through the camera at the museum, how he had been picked because of their shared ancestry to start an internet correspondence with her, his journey to Dunedin.

James’s face twisted with contempt. ‘Shared ancestry. When I was young I was in the police in the refugee camps, when rations were so short some of them turned to cannibalism. Don’t think they bothered much about shared ancestry. I saw what people without God are like there. It’s finished, it’s all finished. Don’t you understand that?’

Shiva took a deep breath. ‘The Tasman government have suspected for some time you were planning something big. There were people tracking me everywhere I went. They knew what they were doing. They’ll follow that railway of yours. The best thing you and anyone else in this place who still has a foot in the real world can do is run.’

James looked at him steadily for a long moment, then he shook his head. ‘It’s not a bad story, but I don’t believe you,’ he said. ‘We were watching you carefully all the time you were in Dunedin, and we saw no one following you. We don’t think anyone there has the faintest idea of what we are planning. We’re better organized than you seem to think. You probably think since we’re Christians we’re naive and badly organized, but we’re not.’

‘And you go in for torture and murder,’ Shiva said, gasping at the pain in his shoulder.

‘Read your history,’ James said contemptuously. ‘And don’t try to distract me. I think you came here to hunt down Parvati Karam. I think you’re pretty much alone.’

Shiva did not reply. ‘I’m right, aren’t I?’ James asked, then rose to his feet. Shiva flinched. ‘I’ll leave you for a while. When I come back I’ll have you standing with both arms tied up behind your back. That’ll be worse.’ He looked at Shiva intently. ‘So have a good think about whether you want to stick to that story.’ He untied the cord around Shiva’s neck and tied both hands back to the rope fixed to the ring in the floor. Then, without another word, he left the shed.

An hour passed. It began to get dark, the light coming through the little window fading. Shiva twisted and manoeuvred to find a position that would ease the pain in his shoulder. He knew that when James came back, before long he would tell him the truth. He thought about the ancient monk who had written the verses. If he had not written that wretched book, none of this would have happened; he would not be here. ‘Couldn’t you see people would do something like this with your book, you fool?’ he asked aloud.

He heard a fluttering sound. One of the mangy-looking parrots was at the window again, perhaps the same one. It stood on the sill and looked at Shiva, then at the bowl on the floor. It must have smelled the congealing remains of the stew but was obviously frightened to fly into the shed. Shiva looked at the hooked, sharp beak and remembered the one on the post that had been chewing at the rope. Very slowly and gently, so as not to startle the kea, Shiva edged painfully over to the bowl and, gritting his teeth, put his bound wrists inside it. He dipped the piece of rope connecting them into the watery mess. The kea watched intently.

Shiva hoped its hunger was stronger than its fear. He lifted his hands out again and managed to pick up the bowl. He shuffled back against the wall. He put the bowl on his lap, held his roped wrists beside it. The bird twisted its head from side to side, assessing what was going on. Parrots, Shiva knew, were intelligent birds.

‘Come on,’ Shiva said encouragingly. ‘Come on.’

It hesitated, then fluttered down to the floor. It stood there out of reach, studying him without moving. Shiva closed his eyes and leaned his head wearily against the wall. This wasn’t going to work.

He felt a wind, then sharp little claws on his thigh. He opened his eyes. The parrot was perched on his leg and had put its head into the bowl. A dark little tongue flickered out of the open beak, greedily licking up the remains of the stew in the bottom of the bowl. He saw how thin it was. The bird kept one eye beadily fixed on Shiva. When it had finished, it jumped into the empty bowl and looked at Shiva’s bound wrists. There was a little of the stew on his fingers, and he feared the bird might bite them. The kea looked up at his face uncertainly for a moment, then stretched its head forward and began picking at the rope.

Some instinct to grub and peck had been stimulated, for the kea bit and tugged, swallowing pieces of rope as well as the stew smeared on it. Shiva sat as still as a stone, enduring his pain. The bird bit his wrists several times and blood began to flow, but he gritted his teeth and made no sound that might startle it. After about fifteen minutes the bird suddenly stopped, then flew up, perched on the windowsill for a moment, and was gone.

Though it brought pain to his shoulder, and to his wrists too now, Shiva tugged at the ropes. The strand linking his wrists was almost severed, and the kea’s pulling and pecking had loosened the others. He felt something give, and pulled his right hand free. He looked at his wrists; his hands and wrists were dotted with sharp little cuts, many bleeding. With his free hand he began picking at the ropes until both hands were free, then his legs. He arranged the ropes so it looked as though his limbs were still tied, then leaned back against the wall, breathing hard, trying to pull himself together. He arranged his hands in his lap so it looked as though they were still tied. Then he leaned back against the wall again, grateful for the dim light. The trousers of his best suit were dark with grime and dust now.

This time it was only a few minutes before he heard footsteps approaching the hut. The key turned. But it wasn’t James who came in, it was Parvati. She carried a gun, a large old revolver that looked huge in her little hand. In her other hand she carried an olive-oil lamp which she laid on the floor. She stood looking down at him. Her expression was annoyed, irritated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Lost Prophecies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Lost Prophecies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Lost Prophecies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.