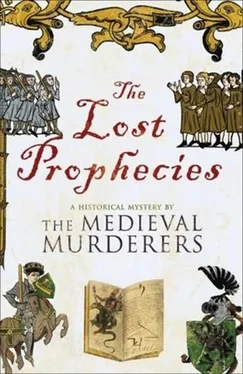

The Medieval Murderers - The Lost Prophecies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «The Medieval Murderers - The Lost Prophecies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Lost Prophecies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Lost Prophecies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Lost Prophecies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Lost Prophecies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Lost Prophecies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Thomas de Peyne, who had listened breathlessly to the sheriff’s account, was suddenly assailed by a dreadful revelation.

This was that quatrain come to fulfilment! It was the words ‘the budding elm’ that triggered his recognition, for it was April now, when the new shoots would be appearing on the trees. Now the words ‘a bearded champion fought oppression’s realm’ made complete sense, as did the rest of the verse.

He crossed himself repeatedly as he bitterly regretted adding his own foolish sneer to the copy of Brân’s Black Book, rashly warning other readers not to believe everything they read. If the warning from centuries ago about Fitz-Osbert’s actions and the further desecration of sanctuary – by the Archbishop of Canterbury himself – was true, what other terrible portents were forecast and would eventually come to pass?

Shaking with remorse, he forced himself to listen to the end of Henry de Furnellis’s account.

‘Though the Justiciar had effectively destroyed the rebellion, he is being reviled in London by both common folk and churchmen alike for his high-handed actions, and there is talk that the king will be petitioned to have him removed from office.’

He shook his grey head in despair. ‘This was a bad time for England. The hatred of the population for harsh authority and the ruthlessness of the king’s officer have weakened the bonds of loyalty to a king, who appears unconcerned with what happens this side of the Channel. The feelings of the men of London were shown by the way in which they acted at the execution site, this place Tyburn, which was used instead of Smithfield as the traditional place for the dispatch of traitors.’

‘What d’you mean, sheriff, what actions of the populace?’ asked de Wolfe.

‘During the night, the bodies of Longbeard and his men were taken down by the saddened citizens, and the very chains in which they were hanged were broken up and distributed to the sympathizers as talismans of their respect. Not only that, but hundreds of common folk came to retrieve handfuls of earth from under the elm, below where the men had died. By next day there was a huge hole under where they had swung, such that Hubert Walter had to station troops to keep more folk away.’

When the story was rounded off, with admonitions from the sheriff to watch for similar signs of unrest in Exeter, the coroner’s trio went back to their chamber in the gatehouse and sombrely discussed the sheriff’s news.

Thomas decided to keep his revelations about the prophecy in Brân’s Black Book to himself, mainly because of his regret at having rashly added such a dismissive verse. With both the original and the copy now gone to London – and, who knows, perhaps onward to Rome – he felt it best to keep quiet about his stupid and immature action.

‘Let other generations decide about the quatrains for themselves,’ he muttered under his breath. ‘Let God’s will be done in His own time. We have no business in trying to anticipate what the Almighty has in store for us!’

He went back to sorting out the archives, a chastened but wiser man.

HISTORICAL NOTE

The abortive revolt organized by William Fitz-Osbert was the first of a line of rebellions in England rousing the common man against oppressive authority – later came John Ball, Wat Tyler and others. Much of the severe ill feeling against Archbishop Hubert Walter was not so much for his ruthless suppression of the revolt but for his breaking of sanctuary at St Mary le Bow, too reminiscent of the traumatic quarrel between Henry II and Thomas à Becket in 1170.

Some accounts claim that Fitz-Osbert was hanged at the Smithfield elms, but it was on the Tyburn elm that he expired, probably the first of thousands to die there for almost six hundred years up to 1783.

ACT TWO

Tartarus’ hordes irrupt through Alexander’s gate.

Six Christian kingdoms crumble in a breath.

Though Latin traders use long spoons to eat,

It won’t protect them from a demon’s death.

I snatch the kumiss from the Tartar’s hand and, tipping the leather sack up, I throw my head back. The raw, milky-white fluid gurgles out of the sack and hits the back of my throat like a well-aimed arrow. I relish the sting on my tongue and the fizz as the kumiss gurgles down. Drinking half-fermented mare’s milk is an acquired taste, but one to which I have adjusted. When you’re thousands of miles from a good Rhenish, and the craving’s on you, you’ll drink anything that’ll guarantee to get you legless. Too much of it, though, and you end up seeing stars. Still and all, that’s better than sharing your quarters with a dead man.

I should explain. The year is Ren-Xu – the Tartar year of the dog – and the year 660 for Mohammedans. To you and me it is the ninth year of Doge Renier Zeno’s governance of Venice, the second year of Pope Urban the IV’s reign, and one thousand two hundred and sixty-two years since the birth of Christ. Or at least I think it is. I have been away from civilization for too long now. And I have lost count of the days that have passed, like a sailor lost at sea. The mare’s milk brew hasn’t helped in keeping my head straight either. All I can say for sure is that it is several months since Friar Giovanni Alberoni, a fellow Venetian (albeit from that sharp, shingle strip that edges the lagoon), picked me up out of the gutter in Sudak.

‘Niccolo Zuliani? Is it really you? I can hardly recognize you.’

‘No, I’m not .. . who you say. My name’s .. . Carrara, Francesco Carrara.’

‘Nonsense. I know Francesco Carrara. He’s at least twenty years older than you, and considerably larger in girth.’

I was so addled at the time that I didn’t quibble any further over my embarrassment at being found in that state. Nor about the friar’s reinstatement of my real name, which I had avoided using for some time. In Venice it was the name of a wanted man. Alberoni always calls me Niccolo in that formal, stuffy way of his. My true friends use the more familiar Nick just as my English mother did, but for the moment I was glad to be Niccolo again at least. He helped me get to my feet and supported my enfeebled body.

‘I’m glad I found you. I have a proposition for you.’ So it was that the gutter in Sudak became the crossroads of my life. Sudak is in Gothia, by the way – some call it Crimea – on the northern side of the Black Sea close to the icy fastnesses of Russia, which are controlled by the Golden Horde. Its main claim to fame is as a point of contact between us Latins and those mysterious Tartars of the East. It was there the good friar nursed me back to something resembling health and fired my imagination with the prospect of plundering the fabled wealth of the Tartar Empire. Well, to be honest (a trait some say I lack, though they tend to be prejudiced, having been outwitted by me in some deal or other) – to be honest, I was the one wanting to do the plundering. Alberoni wanted to penetrate the distant depths of the Empire in order to spread the word of God to the heathen.

Myself, I go for more modest scenarios in order to make a living. I had been living in Sudak, albeit rather poorly, off a scam that we Venetians call ‘the long trade’. Don’t ask me why. The trick is to set up a company in a false name, or with a gullible but reputable fool as a front. Using the fool’s reputation, you then obtain goods on credit over a long period, paying small deposits to keep your creditors happy. Then you rapidly sell off everything you have stored very cheaply, and finally disappear in order to avoid those creditors. Leaving the front man to take the blame. Simple, as long as you can hold your nerve. I lost mine when I was threatened by a big bear of a fur trader from Russia and came out with nothing. I should have stuck to honest trading, especially as the only other time I had reached for the stars had been an unmitigated disaster too. You may recall that I tried to rig the Doge’s election to no avail, ending up with a murder rap. In short, that’s why I had been holed up in Sudak using fat old Carrara’s name as my own.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Lost Prophecies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Lost Prophecies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Lost Prophecies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.