“I shall publish, sir, when I am minded so to do.”

Wallis tried to conceal his show of exasperation, with little success.

“The business of the Mint, you say?” he said, changing the subject. “I had heard you were Master of the Mint. From Mister Hooke.”

“For the present I am merely the Warden. The Master is Mister Neale.”

“The Lottery man?”

Smiling thinly, Newton nodded.

“But is the work so very challenging?”

“It is a living, that is all.”

“I wonder that you do not have a church living. I myself have the living of St. Gabriel’s in London.”

“I have not the aptitude for the Church,” replied Newton. “Only for inquiry.”

“Well then, sir, I am at the Mint’s service, although if we are to talk of money, I can tell you there’s none in the whole of Oxford.” Wallis gestured at his own surroundings. “And I cannot counterfeit anything save this show of worldly comfort. The only silver hereabouts is the college plate, and all sober men of the University are fearful of ruin. This Great Recoinage has been badly handled, sir.”

“Not by me,” insisted Newton. “But I have come about a book, sir, not the scarcity of good coin in Oxford.”

“We have plenty of those, sir,” said Wallis. “Sometimes I would we had fewer books and more money.”

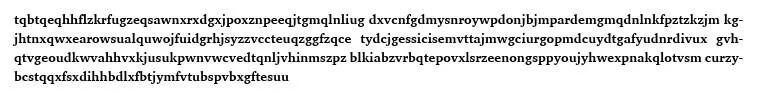

“I seek a particular book — Polygraphia , by Trithemius — which I would desire to have sight of.”

“You have come a long way to read one ancient book.” The old man got up from his chair and fetched a handsomely bound volume from his bookcase.

“Polygraphia , eh? That is an ancient book indeed. It was first published in 1517. This is an original copy which I have owned these past fifty years.”

“But did you not order another from Mister Lowndes of the Savoy?” asked Newton.

“Who told you that, sir?”

“Why, Mister Lowndes, of course.”

“I like this discovery not, sir,” said Wallis, frowning. “A man’s bookseller should keep his confidence, like his physician. What can become of a world where every man knows what another man reads? Why, sir, books would become like quacks’ potions, with every mountebank in the newspapers claiming one volume’s superiority over another.”

“I regret the intrusion, sir. But as I said, this is official business.”

“Official business, is it?” Wallis turned the book over in his hands and then stroked the cover most lovingly.

“Then I will tell you, Doctor. I bought another copy of Polygraphia for my grandson William. I have been teaching him the craft in the hope that he will follow in my footsteps, for he demonstrates an early aptitude.”

An early aptitude in what? I wondered. For writing? Neither Newton nor I yet had any real idea what this book by Trithemius was about.

“Trithemius is a useful primer in the subject, sir,” continued Wallis, handing the book to Newton. “Although I do not think his book could long detain a man such as you. Porta’s book, De Furtivis Literarum Notis , is more suited to your intellectual parts. Perhaps also John Wilkins’s Mercury, or The Swift and Secret Messenger . You may also prefer to read John Falconer’s Cryptomenytices Patefacta , which is most recent.”

“Cryptomeneses,” Newton murmured to me as Wallis took down two more books from his shelves. “Of course. Secret intimations. I did not understand until now.” And seeing me remain still puzzled, he added, with greater vehemence, “Cryptographia , Mister Ellis. Secrecy in writing.”

“What’s that you say?” asked Wallis.

“I said I should like to read this one, too.”

Wallis nodded. “Wilkins teaches only how to construct a cipher, not how to unravel one. Only Falconer is practical, for he suggests methods of how ciphers may be understood. And yet I think that a man who wishes to solve a cryptogram is always best advised to trust to his own industry and observation. Do you not agree, Doctor?”

“Yes sir, I have always found that to be my own best method.”

“And yet it is hard service for a man of my years. Sometimes I have spent as long as a year on a particular decipherment. Milord Nottingham did not understand how long these things can take. He was always pressing me for quick solutions. But I must stand the course, at least until William is ready to take over the work. Although there is very little reward in it.”

“It is the curse of all learned men to be neglected,” offered Newton.

Wallis was silent for a moment, as if much pondering what Newton had said.

“Well, that is odd,” he said finally. “For now I remember that someone else from the Mint came to see me about a year ago. Your pardon, Doctor Newton. I had quite forgotten. Now, what was his name?”

“George Macey,” said Newton.

“The very same. He brought with him a small sample of a code I had never before encountered, and expected me to work a miracle with it. Naturally. They all do. I told him to bring me some more letters and then I would stand a chance of overcoming the difficulty of it. He left the letter with me, but I had no luck, for it was the hardest I ever met with, though as I said, I had not enough material to be assured of any success. And I put it aside. I had not thought of it again until now, but I never heard from Mister Macey again.”

Upon hearing Wallis mention a letter, I almost saw Newton’s cold heart miss a beat. He sat forward on his chair, chewed the knuckle of his forefinger for a moment, and then asked if he might see the letter Macey had left behind.

“I am beginning to understand what this is all about,” said Wallis, and fetched the letter from a pile of papers that lay upon the floor. He seemed to know where everything was, although I could see no great evidence of order; and handing my master the letter, he offered him some advice also.

“If you do attempt this decipherment, then let me know how you fare. But always remember not to rack your mind over-anxiously, for too much brain work with these devices is enervating, so that the mind is fit for nothing afterwards. Also be mindful of what Signor Porta says, that when the subject is known, the interpreter can make a shrewd guess at the common words that concern the matter in hand, and in this way a hundred hours of labour may be saved.”

“Thank you, Doctor Wallis. You have been most helpful to me.”

“Then reconsider your decision about your Opticks , sir.”

Newton nodded. “I will think about it, Doctor,” he said.

But he did not.

After this, we took our leave of Doctor Wallis with Newton in possession of the new sample of enciphered material as well as several useful books; so that he was hardly able to contain his excitement, although he was very swiftly angry with himself that he had not thought to bring with him the other enciphered material that was already held by us.

“Now I shall not be able to work on the problem while we are in that damned coach,” he grumbled.

“May I see the message?” I asked.

“But of course,” said Newton, and showed me the letter that Wallis had given to him. I looked at it for a while, but it was no more clear to me now than it had ever been.

I shook my head. Merely to look at the jumble of letters dispirited me, and I could not see how anyone could enjoy cudgelling his brains with its solution.

“Perhaps you can read one of these books that Doctor Wallis has lent to you,” I offered, which partly placated him, for he liked nothing better than a longish journey with a good book.

Читать дальше