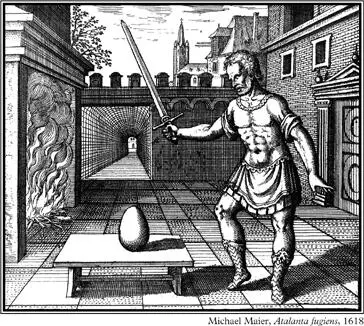

It being late, the present Keeper of the Records was not to be found and I wandered among the shelves that were arranged behind the simple stone capitals of the outer aisles. Upon these lay books and records which I was now resolved thoroughly to know whenever I found myself with sufficient time. Underneath the tribune gallery stood a great refectory table upon which lay an open book that I perused idly. And, doing so, was much surprised to discover a bookplate that proclaimed the book to be from the library of Sir Walter Raleigh. This book, which I examined for the love of the binding, it being most fine, disturbed me greatly, for it contained a number of engravings, some of which seemed so lewd that I wondered that the book was ever read in a chapel. In one picture a woman had a toad suck at her bare breast, while in another a naked girl stood behind an armoured knight urging him to do battle with a fire; a third picture depicted a naked man coupling with a woman. I was more repelled than fascinated by the book, for there was something so devilish and corrupt about the pictures it contained that I wondered how a man like Sir Walter could have owned it. And upon returning soon thereafter to the north-east turret, I thought to mention that it seemed indecent to leave such a book lying around so that any might examine it.

At this Newton left off looking through his telescope and straightaway accompanied me back down to the second floor, where, in the chapel, he examined the book for himself.

“Michael Maier of Germany was one of the greatest hermetick philosophers that ever lived,” he remarked as he turned the book’s thick vellum pages. “And this book, Atalanta Fleeing , is one of the secret art’s great books. The engravings to which you objected, Mister Ellis, are of course allegorical, and although they are in themselves difficult to understand, they serve no indecent purpose, so you may rest assured on that count. But it was open, you say?”

I nodded.

“At which page?”

I turned the pages until I came upon the engraving of a lion.

“In the light of what happened to Mister Kennedy,” he said, “the page being open at the Green Lion may be suspicious.”

“There is a bookplate,” I said, turning back the pages. “And I showed him Raleigh’s bookplate.

Newton nodded slowly. “Sir Walter was imprisoned here for thirteen years. From 1603 until 1616, when he was released in order that he might redeem himself by discovering a gold mine in Guiana. But he did not, and upon his return to England he was imprisoned in the Tower once again, until his execution in 1618. The same year as this book.”

“Poor man,” I exclaimed.

“He merits your pity, right enough, for he was a great scholar and a great philosopher. It is said that he and Harry Percy, the Wizard Earl, being rightly minded, where possible, to avoid any hypothetical explications, carried out some experiments in matters hermetick, medical and scientific in this very Tower. Thus the book may indeed be accounted for, but not why it is being read now. I shall make sure to ask the Keeper of the Records who has been examining this book when next I see him. For it may that it shall give us some apprehension of who might have murdered poor Mister Kennedy.”

THIS THEN IS THE MESSAGE WHICH WE HAVE HEARD OF HIM, AND DECLARE UNTO YOU, THAT GOD IS LIGHT, AND IN HIM IS NO DARKNESS AT ALL.

(FIRST EPISTLE OF JOHN 1:5)

Michael Maier, Atalanta fugiens , 1618

Upon leaving the White Tower, where Newton had observed Orion through his telescope, he and I returned to the office, where we fell to discussing the murder of poor Mister Kennedy and the disappearances of Daniel Mercer and Mrs. Berningham for whose arrests Newton now wrote out the warrants.

“Yet I do not think we shall find them,” he said as he handed me the papers. “Mrs. Berningham is very likely on board ship by now. While Daniel Mercer is very likely dead.”

“Dead? Why do you say so?”

“Because of the message that was left at his lodgings. Those hermetick clues that we found upon the table almost told me as much. And because none of his own possessions were taken away. The new beaver hat that lay upon the chair would have cost almost five pounds. A man does not leave such a hat behind when he leaves somewhere of his own accord. No more would he have left a good warm cloak in such cold weather as this.”

As usual the logic of Newton’s arguments was inescapable.

I was about to suggest to my master that I should like to go to bed, for it was quite late, when there was a loud knock at the door and old John Roettier entered the Mint office.

John Roettier was one of an old family of Flanders engravers who had worked in the Mint since the restoration of King Charles. His was an odd situation: he was a Roman Catholic whose brothers Joseph and Phillip had gone to work in the mints of Paris and Brussels and who had been replaced by Old John’s two sons, James and Norbert. These two were recently fled to France, with James accused of having joined in a treasonous conspiracy to kill King William. All of which left the old man alone in the Mint, cutting seals and suspected by the Ordnance of being a traitor on account of his religion and his treacherous family. But Newton liked and trusted him well enough and accorded him the degree of respect that was due to anyone who has given public service for many years. He was a slow, steady sort of man, but straightaway we perceived that he was greatly perturbed by something.

“Oh sir,” he exclaimed. “Doctor Newton. Mister Ellis. Such a horrible thing has happened. A murder, sir. A most dreadful horrible murder. In the Mint, sir. I never saw the like. A body, Doctor.” Roettier sat down heavily on a chair and swept an ancient-looking wig off his head. “Dead, quite dead. And most awful mutilated, too, but it is Daniel Mercer, of that I am certain. Such a sight, sir, as I never saw until this night. Who would do such a thing? Who, sir? It is beyond all humanity.”

“Calm yourself, Mister Roettier,” said Doctor Newton. “Take a deep breath in order that you might give some air to your blood, sir.”

Old Roettier nodded and did as he was bid; and having drawn a deep breath, he replaced the wig upon his head so that it looked like a saddle on a sow’s back and, gathering his wits, explained that Daniel Mercer’s body was to be found in the Mint, at the foot of the Sally Port stairs.

Newton calmly fetched his hat and cloak and lit the candle in a storm lantern. “Who else have you told about this, Mister Roettier?”

“No one, sir. I came straight here from my evening walk about the Tower, sir. I don’t sleep so good these days. And I find a little night air helps to settle me some.”

“Then snug is the word, Mister Roettier. Tell no one what you have seen. At least not yet. I fear this news will greatly disrupt the recoinage. And we shall try to keep this from the Ordnance as long as possible, lest they think to interfere. Come on, Ellis. Stir yourself. We have work to do.”

We came out of the office and walked north up the Mint, as if we had been going to my house, bracing ourselves against a cold wind that stung our faces like a close razor. Between my own garden and an outhouse where Newton kept some of his laboratory equipment, the Sally Port stairs led up from the Mint to the walls of the Inner Ward and the Brick Tower, where the Master of the Ordnance now lived.

Old Roettier had not exaggerated. In the sinuous light of our lanterns my master and I beheld such a sight as only Lucifer himself might have enjoyed. At the foot of the stairs, so that he almost looked as if he might have missed his footing in the dark and fallen down, lay the body of Daniel Mercer. Except that his head had been neatly severed and now lay on its neck upon one of the steps; and from this the two eyes had been removed, which lay upon a peacock’s feather of all things, which itself lay beside a flute. While on the wall were chalked the letters

Читать дальше