‘Was the collector at Star Court not apprehended or followed?’ asked Joseph.

‘Unfortunately not. My warning was not, it seems, received in time.’

‘A pity. Is there any significance in the name Silver?’ asked Thomas.

‘Not that we are aware of. It is the code that interests us. It is entirely numeric. We haven’t come across that before, have we, gentlemen?’ Williamson inclined his head in agreement. Morland remained impassive. ‘Does that suggest anything to you, Thomas?’

‘When a new code or encryption appears, it is invariably because the contents of the message are too sensitive for an old one to be used. This is especially the case when the message is travelling along an established route.’

‘That is common knowledge,’ observed Morland drily. It was his first contribution to the discussion. ‘Can Mr Hill offer any other advice?’

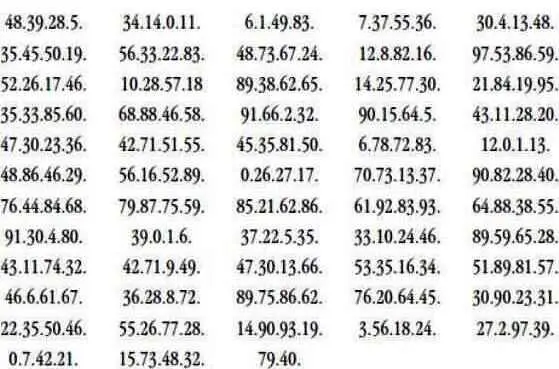

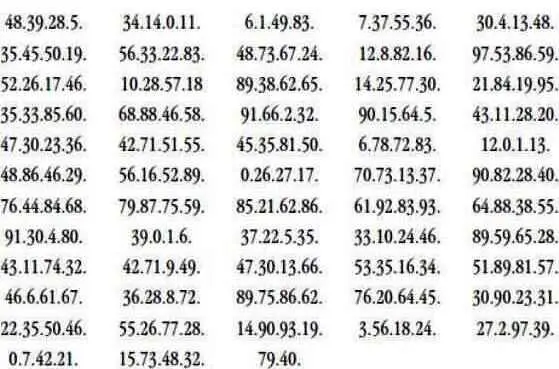

‘May I see the copy?’ Williamson passed it to him. Thomas opened it and spread it on the table. There were eleven and a half lines of numbers, grouped in fours. Each number was separated by a stop and consisted of one or two digits. There were no three-digit numbers.

There were too many different numbers for the code to be a straightforward substitution. He noticed a number of repetitions and such a code would have been quite inadequate against a competent cryptographer. There was more to it and it would require hard work to find out what.

‘This is a complex substitution cipher,’ he said, almost to himself. ‘It can be broken, but it will take some time.’

‘How much time?’ demanded Morland imperiously.

‘A few days, I think,’ replied Thomas, still studying the letter.

Morland was unimpressed. ‘Come now, Master Hill, it is clear to anyone with eyes to see that these numbers represent not letters, but syllables and words. It is a code, not a cipher. That is why there are so many different combinations. How do you intend to break such a code within “a few days”?’

Morland was wrong. There were too many repetitions. Syllables and words did not feel right to Thomas, just as a bream biting on a hook did not feel like a trout. You could not be entirely sure until the fish was safely in the net, but you would wager a shilling or two as soon as you felt it bite. ‘Hill’s magic’, dear Abraham Fletcher used to call it – an uncanny ability to divine the nature of a code or encryption just by looking at it and by conjuring up an image of the encrypter. This message had been written by an educated hand with elaborate neatness. The encryption would be clever but straightforward. There was no point, however, in arguing with Morland.

‘Sir Samuel may well be right, gentlemen. It might be a code and complex codes can take time to unravel, especially with only one document to work on. I suggest that he sets to work without delay.’

‘That is one of Master Hill’s more sensible suggestions,’ said Morland, with a smirk. ‘If anyone can decode this, it is I.’

Williamson and Bishop exchanged glances. ‘We would prefer you to continue with the important work you are engaged in, Samuel,’ said Williamson tactfully. ‘Your new family of ciphers is keenly anticipated and much needed.’

Morland looked furious. ‘Nonsense. The decoding of this message is much more urgent than the new ciphers and I am by far the best man to do it.’

‘Do you not think that Thomas is as well qualified? He did break the Vigenère square and he knew the double vowel substitution cipher when he saw it.’

‘Tush. The vowel substitution is simple and he broke the square with a lucky guess.’

Just as they had at their last meeting, Thomas’s hackles rose. The second message encrypted with the square he had indeed decrypted with a guess – inspired rather than lucky, he liked to think – but the first one had been the result of a vital insight and logical thought. How dare this unpleasant man suggest otherwise? With difficulty, he kept his tone measured. ‘Sir Samuel doubtless has his reasons for holding such an opinion of me, but he is mistaken about this message. It does not use codes for syllables or words and I can decrypt it within two days.’

A tiny smile played across Williamson’s face. ‘If Thomas says he can decrypt the letter within two days, I am inclined to believe him. What do you think, Henry?’

‘I agree.’

‘Then he must have the chance. You won’t let us down, Thomas, will you?’

I had better not, thought Thomas. Morland is a pig and I want to go home. ‘You may rely on me, gentlemen.’

‘Ridiculous,’ spluttered Morland and stormed out of the room.

Lemuel Squire, who had sat quietly and said nothing, took a pinch of snuff and sneezed loudly. ‘Really, that man is quite the rudest in London. I do apologize, Thomas. His behaviour was unforgivable. I shall go and tell him so.’ And he followed Morland out.

‘You are sure of this, Thomas, I hope?’ asked Bishop.

Sure? Not even half sure. A complex substitution cipher in two days? It would take all of Hill’s magic and a hatful of luck. ‘Quite sure, sir.’

‘In that case take the copy and start at once. There is no time to lose,’ said Williamson.

Then I’d better be right about it, thought Thomas, or I shall look a fool and Morland will love it.

‘How did you come to arrive at my door this morning, Thomas?’ asked Williamson, on their way back to Chancery Lane. ‘Was it mere chance or had you a reason for calling so early?’

‘I had a reason, Joseph. But now it must wait until I’ve decrypted this letter.’

‘Only a day or two, then? This might be just the stroke of luck we need. It could lead us to the heart of the enemy.’

‘To be sure. Only a day or two.’

In his room at Williamson’s house, Thomas spread the copy of the encrypted message on his table.

The letter had come from Holland and might shed light on the suspected spy ring. If so, and assuming it had been written in English, it might contain such words as England, London, agent, king, or even invasion.

Thomas closed his eyes and tried to visualize the man who had encoded this letter. He saw a middle-aged man, precise in word and dress, an orderly man not given to flights of fancy or expansive gestures. A man in control of himself and his life. A man who wrote in an educated hand with elaborate neatness. There were no corrections that Thomas could discern and the numbers were set out in tidy groups. This was not a man who would use tricks or deliberate mistakes to confuse his enemy but would rely upon his art and technique. He would favour a straightforward cipher. A Caesar, not a Cicero.

He turned his attention back to the message itself and started counting. In decryption much time was spent in counting. There were two hundred and thirty numbers in fifty-seven and a half groups of four. The spaces between groups were certainly irrelevant. No message of this length had ever been written using only four-letter words. Then he counted individual numbers. Ninety-one numbers between 0 and 97 had been used with frequencies varying from seven (28) to one. Numbers 41, 54, 63, 69, 94, 95 and 96 had not been used, either because the letters they represented had not appeared in the plain text message or because they had not been allocated to a letter. The same might be true of numbers 98 and 99. Ninety-seven numbers for a maximum of twenty-six letters meant that at least some letters were represented by more than one number. The question was: had they been allocated randomly or was there some pattern to be found?

All day, without food or drink, Thomas laboured away. By the time his stomach started complaining he had got through ten quills, the floor was littered with discarded papers and his fingers were stained with ink. And he had learned very little. Concentrating on the most frequent numbers – 28, 30, 35 and 46 – he had counted and recounted, attempted a few guesses, tried in vain to gain a foothold by examining the juxtapositions of the numbers, hoping to find two that might represent TH, CH, OU or another common pair, and he had searched in vain for possible vowels and double letters. He had found no hint of pattern. At five o’clock he stood up, stretched his aching back, rubbed his eyes and walked to the window. It was a lovely summer evening and he needed to breathe fresh air. Having carefully locked the door of his room behind him, he let himself out of the house and went for a walk.

Читать дальше